Laura K. brought our attention to these ads with not-so-subliminal sexual content (via haha.nu). Some of them are so-not-so-subliminal that they may not be safe for work.

Search results for sex in advertising

Ok, so this isn’t an image, but it seemed like something our readers might be interested in, so I’m making an exception. Larry (of The Daily Mirror) sent in a link to this story in the New York Times about efforts by the European Union to discourage sex stereotyping in ads (I think another reader also sent in the link, but I’m afraid I’ve lost the email; if it was you, let me know and I’ll give you credit!). From the article:

The European Parliament has set out to change this. Last week, the legislature voted 504 to 110 to scold advertisers for “sexual stereotyping,” adopting a nonbinding report that seeks to prod the industry to change the way it depicts men and women.

Interestingly, the author of the article refers to the measure as “laughable as a gesture of political correctness.” Advertising industry leaders call into question the link between stereotypical images and actual discriminatory or problematic outcomes in actual life. It brings up a recurring issue cultural critics face–it can be extremely difficult to show that, say, sexualized images of women leads to any particular negative outcome. We may strongly believe that the ubiquitous presence of ads that show stereotypical gender roles reinforce them…but since we haven’t yet created a society similar to our own except without the stereotyping, it’s hard to isolate the effects of such cultural messages because we can’t compare what our culture would be like without them.

Thanks, Larry!

Originally posted at Gender & Society

Last summer, Donald Trump shared how he hoped his daughter Ivanka might respond should she be sexually harassed at work. He said, “I would like to think she would find another career or find another company if that was the case.” President Trump’s advice reflects what many American women feel forced to do when they’re harassed at work: quit their jobs. In our recent Gender & Society article, we examine how sexual harassment, and the job disruption that often accompanies it, affects women’s careers.

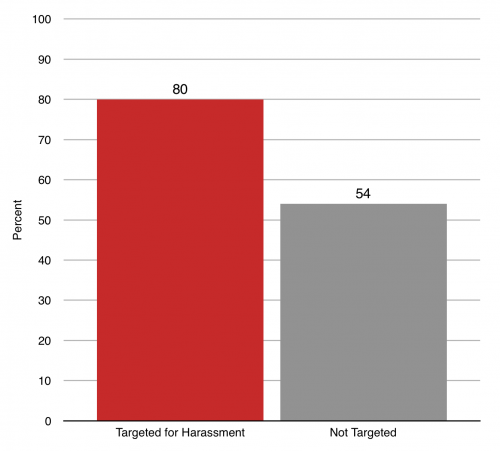

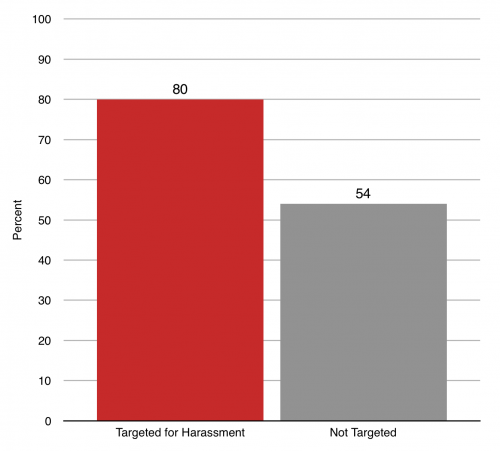

How many women quit and why? Our study shows how sexual harassment affects women at the early stages of their careers. Eighty percent of the women in our survey sample who reported either unwanted touching or a combination of other forms of harassment changed jobs within two years. Among women who were not harassed, only about half changed jobs over the same period. In our statistical models, women who were harassed were 6.5 times more likely than those who were not to change jobs. This was true after accounting for other factors – such as the birth of a child – that sometimes lead to job change. In addition to job change, industry change and reduced work hours were common after harassing experiences.

Percent of Working Women Who Change Jobs (2003–2005)

In interviews with some of these survey participants, we learned more about how sexual harassment affects employees. While some women quit work to avoid their harassers, others quit because of dissatisfaction with how employers responded to their reports of harassment.

Rachel, who worked at a fast food restaurant, told us that she was “just totally disgusted and I quit” after her employer failed to take action until they found out she had consulted an attorney. Many women who were harassed told us that leaving their positions felt like the only way to escape a toxic workplace climate. As advertising agency employee Hannah explained, “It wouldn’t be worth me trying to spend all my energy to change that culture.”

The Implications of Sexual Harassment for Women’s Careers Critics of Donald Trump’s remarks point out that many women who are harassed cannot afford to quit their jobs. Yet some feel they have no other option. Lisa, a project manager who was harassed at work, told us she decided, “That’s it, I’m outta here. I’ll eat rice and live in the dark if I have to.”

Our survey data show that women who were harassed at work report significantly greater financial stress two years later. The effect of sexual harassment was comparable to the strain caused by other negative life events, such as a serious injury or illness, incarceration, or assault. About 35 percent of this effect could be attributed to the job change that occurred after harassment.

For some of the women we interviewed, sexual harassment had other lasting effects that knocked them off-course during the formative early years of their career. Pam, for example, was less trusting after her harassment, and began a new job, for less pay, where she “wasn’t out in the public eye.” Other women were pushed toward less lucrative careers in fields where they believed sexual harassment and other sexist or discriminatory practices would be less likely to occur.

For those who stayed, challenging toxic workplace cultures also had costs. Even for women who were not harassed directly, standing up against harmful work environments resulted in ostracism, and career stagnation. By ignoring women’s concerns and pushing them out, organizational cultures that give rise to harassment remain unchallenged.

Rather than expecting women who are harassed to leave work, employers should consider the costs of maintaining workplace cultures that allow harassment to continue. Retaining good employees will reduce the high cost of turnover and allow all workers to thrive—which benefits employers and workers alike.

Heather McLaughlin is an assistant professor in Sociology at Oklahoma State University. Her research examines how gender norms are constructed and policed within various institutional contexts, including work, sport, and law, with a particular emphasis on adolescence and young adulthood. Christopher Uggen is Regents Professor and Martindale chair in Sociology and Law at the University of Minnesota. He studies crime, law, and social inequality, firm in the belief that good science can light the way to a more just and peaceful world. Amy Blackstone is a professor in Sociology and the Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center at the University of Maine. She studies childlessness and the childfree choice, workplace harassment, and civic engagement.

The 2017 Super Bowl was an intense competition full of unexpected winners and high entertainment value. Alright, I didn’t actually watch the game, nor do I even know what teams were playing. I’m referring to the Super Bowl’s secondary contest, that of advertising. The Super Bowl is when many companies will roll out their most expensive and innovative advertisements. And this year there was a noticeable trend of socially aware advertising. Companies like Budweiser and 84 Lumber made statements on immigration. Airbnb and Coca-Cola celebrated American diversity. This socially conscious advertising is following the current political climate and riding the wave of increasing social movements. However, it also follows the industry’s movement towards social responsibility and activism.

One social activism Super Bowl commercial that created a significant buzz on social media this year was Audi:

The advertisement shows a young girl soapbox racing and a voiceover of her father wondering how to tell her about the difficulties she is bound to face just for being female. This commercial belongs to a form of socially responsible advertising often referred to as femvertising. Femvertising is a term used to describe mainstream commercial advertising that attempts to promote female empowerment or challenge gender stereotypes.

Despite the Internet’s response to this advertisement with a sexist pushback against feminism, this commercial is not exactly feminist. While at its core this advertisement is sending a fundamentally feminist argument of gender equality and fair wages, it feels disempowering to have a man explain sexism. It feels a little like “mansplaining” with moments reminiscent of the male “savior” trope. There is also a very timid relationship between the fight for gender equality and the product being sold. The advertisement is attempting to associate Audi with feminist ideals, but the reality is that with no female board members Audi is not exactly practicing what they preach. There are many reasons why ‘femverstising’ in general is problematic (not including contested relationship between feminism and capitalism). Here I will point out three problems with this new trend of socially ‘responsible’ femvertising.

1. The industry

The advertising industry is not known for its diversity nor is it known for its accurate representation women. So right away the industry doesn’t instill confidence in those hoping for more socially aware and diverse advertising. The way advertising works is to promote a brand identity by drawing on social symbols that make products like Channel perfume a signifier of French sophistication and Marlboro cigarettes an icon of American rugged masculinity. Therefore companies are selling an identity just as much as the product itself, while corporations that employ feminist advertising are instead appropriating feminist ideologies.

They are appropriating not social signifiers of an idealized lifestyle, but rather the whole historical baggage and gendered experiences women. This appropriation at its core is not for social progress and empowerment, but to sell a product. The whole industry functions by using these identities for material gain. As feminism becomes more popular with young women, it then becomes a profitable and desirable identity to implement. The whole concept is against feminist ideology because feminism is not for sale. Using feminist arguments to sell products may be better than perpetuating gender stereotypes but it is still using these ideologies like trying on a new style of dress that can be taken off at night rather than embodying the messages of feminism that they are borrowing. This brings us to the next point.

2. Sometimes it’s the Wrong Solution

Lets consider Dove, the toiletries company that has gained a fair amount of notoriety for their social advertising and small-scale outreach programs for women and girls. Their advertisements are famous for endorsing the body positive movement. But in general the connection between female empowerment and what they actually sell is weak. Which makes it feel insincere and a lot like pandering. Why doesn’t Dove just make products that are more aligned with feminist ideologies in the first place? If feminist consumers are what they want, then make feminist products. Don’t try to just apply feminist concepts as an afterthought in hopes of increasing consumer sales.

Dove is a beauty company that is benefiting from products that are aimed at promoting a very gendered ideal of beauty. The company itself is part of the problem so its femvertising makes me feel like Dove (and their parent company Unileaver) is trying to deny that they are playing a huge role in the creation of these stereotypes that they are claiming to be challenging. If you want to really empower women then don’t just do it in your branding start with the products you are making, examine your business model, and challenge the industry as whole. Feminist concepts should run through the entire core of your business before you try to sell it to your consumers. We don’t need feminist advertising, we need a system that is not actively continuing to increase a gender divide where women are meant to be beautiful and expected to purchase the beauty products that Dove sells. Using feminist inspired advertising doesn’t solve this underlying core problem it just masks it. Femvertising therefore is often the wrong solution, or really not even a solution at all.

3. Femvertising shouldn’t have to be a term

We really shouldn’t be in a situation where all advertising is so un-feminist and so degrading towards women that there is a term for advertising that simply depicts women as powerful. When the bar is set so low we shouldn’t praise companies for doing the minimum required to represent women both accurately and positively. We should be holding our advertising, media, and all other forms of visual representation to much higher standards. Femvertising shouldn’t be a thing because we shouldn’t have to give a term to what responsible advertising agencies should be aiming for when they represent women.

So as to not leave you on a depressing and negative note, here are three advertisements that should be acknowledged for actively challenge the norms:

_____________

Nichole Fernández is a PhD candidate in sociology at the University of Edinburgh specializing in visual sociology. Her PhD research explores the representation of the nation in tourism advertisements and can be found at www.visualizingcroatia.com. Follow Nichole on twitter here.

So, Star Wars is out with a new movie and instead of pretending female fans don’t exist, Disney has decided to license the Star Wars brand to Covergirl. A reader named David, intrigued, sent in a two-page ad from Cosmopolitan for analysis.

What I find interesting about this ad campaign — or, more accurately — boring, is its invitation to women to choose whether they are good or bad. “Light side or dark side. Which side are you on?” it asks. Your makeup purchases, apparently, follow.

This is the old — and by “old” I mean ooooooooold — tradition of dividing women into good and bad. The Madonna and the whore. The woman on the pedestal and her fallen counterpart. Except Covergirl, like many cosmetics companies before that have used exactly the same gimmick, is offering women the opportunity to choose which she wants to be. Is this some sort of feminist twist? Now we get to choose whether men want to marry us or just fuck us? Great.

But that part’s just boring. What’s obnoxious about the ad campaign is the idea that, for women, what really matters about the ultimate battle between good and evil is whether it goes with her complexion. It affirms the stereotype that women are deeply trivial, shallow, and vapid. What interests us about Star Wars? Why, makeup, of course!

If David — who also noted the inclusion of a single Asian model as part of the Dark Side — hadn’t asked me to write about this, I probably wouldn’t have. It feels like low hanging fruit because it’s just makeup advertising and who cares. But this constant message that women are genuinely excited at the idea of getting to choose which color packet to use as some sort of idiotic contribution to a battle of good versus evil is corrosive.

Moreover, the constant reiteration of the idea that we are thrilled to paint our faces actually obscures the fact that we are essentially required to do so if we want to be taken seriously as professionals, potential partners or, really, valuable human beings. So, not only does this kind of message teach us not to take women seriously at all, it hides the very serious way in which we are actively forced to capitulate to the male gaze — every. damn. day. — and feed capitalism while we’re at it.

This ad isn’t asking us if we want to be on the dark side or the light side. It’s asking us if we want to wear makeup or wear makeup. It’s not a choice at all. But it sure does make subordination seem fun.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

A new submission inspires me to re-post this great collection of public resistance to advertisements that objectify women.

Adding commentary to the ubiquitous images that surround us can help us to notice, even if just temporarily, that our environment is toxic to our ability to think of all people as full and complete humans. Here are some inspiring examples.

1. An unknown artist pastes the photoshop toolbar on H&M posters in Germany (thanks Dmitriy T.C. and Alison M.).

2. Toban B. (a prolific SocImages contributor, by the way) sent us a set of photographs. These were snapped in Seattle, Washington by Jonathan McIntosh:

3. Commentary on a Special K. ad in Dublin, sent in by Tara C. (Broadsheet).

Text:

Hey there Special-K Lady.

I know you think I should diet

So I can be slim just like you.

thing is, I think I look pretty fabulous

Just the way I am

Also, Special-K tastes like cardboard

so piss off

4. This one was written on by a teenage girl in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. It reads: “I’m sick of sexually tinted images.”

5. Tricia V. sent us an example of this kind of resistance in Haiti. The billboard below is in for a brand of beer called Prestige. Tricia writes: “The writing [along the bottom of] the billboard says “Ko O+ pa machandiz” which translates as ‘Women’s bodies are not merchandise.'” She was impressed at the effort exerted to climb up and write across a full-sized billboard.

6. Ang B. snapped this photo in Madison, Wisconsin:

7. Sasha Albert saw this comment written on a “please excuse our construction” sign at her gym. Someone else had already written: “WEIRD retouching. Give us a real, healthy, normal woman!” Read more at About Face.

See also: my mom has a phd in math. For a classic example, see “If it were a lady, it’d get its bottom pinched.” For an example of backlash to public anti-sexist messages, see this post on defending privilege (trigger warning).

Cross-posted at Ms. Sources: here, here, and here.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

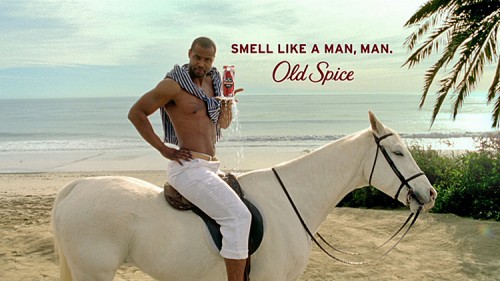

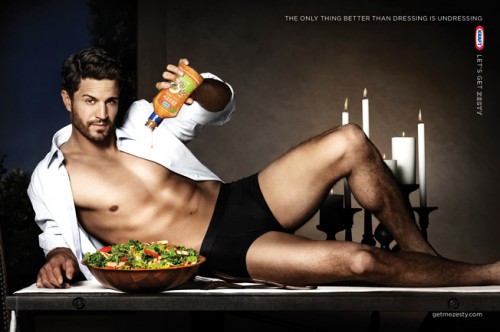

Recently David Gianatasio at AdWeek wrote an analysis of the sudden rise in the sexual objectification of men in advertising. It seems to have been spurred by the wild popularity of the Old Spice character introduced in 2010, The Man Your Man Could Smell Like. Gianatasio calls it “hunkvertising.” Indeed, rippling abdominal muscles suddenly seem to be everywhere.

Gianatasio interviewed me for the piece and I had two thoughts. First, because the ads are so tongue-in-cheek, they didn’t seem to be acknowledging and validating women’s sexual desire, so much as mocking it. “It’s funny to us to think of women being lustful,” I told Gianatasio, “because we don’t really take women’s sexuality very seriously.” In this way, the joke affirms the gender order because the humor depends on us knowing that we don’t really objectify men this way and we don’t really believe that women are the way we imagine men to be.

Second, objectifying men alongside women certainly isn’t progress. There’s the old critique that, if it is equality, it’s not the kind we want. But, more importantly, the forces behind this so-called equality have nothing to do with justice. Gianatasio generously gave me the last word:

I wouldn’t call it equality — I’d call it marketing, and maybe capitalism. Market forces under capitalism exploit whatever fertile ground is available. Justice and sexual equality aren’t driving increasing rates of male objectification — money is.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lindy West for the win at Jezebel, asks what’s so sexualizing about calling a child’s costume “naughty.” The costume below was widely criticized for sexualizing little girls, but West nicely observes that there is a non-sexual, child-related meaning to the word naughty. You know, being bad. The non-sexual version of bad. Doing something you’re not supposed to do. A non-sexual thing. You know what I mean! West writes:

Sure, naughty has had sexual connotations as far back as the mid-19th century, but it’s been used to describe disobedient kids since the goddamn 1600s. So why did we let hornay college chicks hijack the word in all its forms? Why can’t children be naughty anymore?

It’s a great question.

The instinct that “naughty” means “bad and sexy” probably stems in part from our Puritanical roots. Today it gets tied up with the infantilization of women and the notion that women should be cute like girls. Add the rampant sexualization at Halloween, including costumes in which women dress up like little girls dressed up like sexy adult women. It’s hard to see how one could avoid interpreting this “naughty leopard” as an example of the sexualization of little girls.

Nevertheless, West is right. The biggest problem with this costume’s title is that it includes the word “leopard.” Because that’s just false advertising. It doesn’t say sexy leopard and the dress — I’ll stop calling it a costume now — is not particularly sexualizing.

West calls for change:

Why don’t we send “naughty” back from whence it came—into the realm of wedgies and spitballs and pies cooling on the windowsill with bites taken out of them!? It’s time, people. You know it is. Take Back the Naughty. For the children.

And for the grown ups, too, who are tired of the idea that being a sexual person makes us bad, bad girls and boys.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Ok, so this isn’t an image, but it seemed like something our readers might be interested in, so I’m making an exception. Larry (of The Daily Mirror) sent in a link to this story in the New York Times about efforts by the European Union to discourage sex stereotyping in ads (I think another reader also sent in the link, but I’m afraid I’ve lost the email; if it was you, let me know and I’ll give you credit!). From the article:

The European Parliament has set out to change this. Last week, the legislature voted 504 to 110 to scold advertisers for “sexual stereotyping,” adopting a nonbinding report that seeks to prod the industry to change the way it depicts men and women.

Interestingly, the author of the article refers to the measure as “laughable as a gesture of political correctness.” Advertising industry leaders call into question the link between stereotypical images and actual discriminatory or problematic outcomes in actual life. It brings up a recurring issue cultural critics face–it can be extremely difficult to show that, say, sexualized images of women leads to any particular negative outcome. We may strongly believe that the ubiquitous presence of ads that show stereotypical gender roles reinforce them…but since we haven’t yet created a society similar to our own except without the stereotyping, it’s hard to isolate the effects of such cultural messages because we can’t compare what our culture would be like without them.

Thanks, Larry!

Originally posted at Gender & Society

Last summer, Donald Trump shared how he hoped his daughter Ivanka might respond should she be sexually harassed at work. He said, “I would like to think she would find another career or find another company if that was the case.” President Trump’s advice reflects what many American women feel forced to do when they’re harassed at work: quit their jobs. In our recent Gender & Society article, we examine how sexual harassment, and the job disruption that often accompanies it, affects women’s careers.

How many women quit and why? Our study shows how sexual harassment affects women at the early stages of their careers. Eighty percent of the women in our survey sample who reported either unwanted touching or a combination of other forms of harassment changed jobs within two years. Among women who were not harassed, only about half changed jobs over the same period. In our statistical models, women who were harassed were 6.5 times more likely than those who were not to change jobs. This was true after accounting for other factors – such as the birth of a child – that sometimes lead to job change. In addition to job change, industry change and reduced work hours were common after harassing experiences.

Percent of Working Women Who Change Jobs (2003–2005)

In interviews with some of these survey participants, we learned more about how sexual harassment affects employees. While some women quit work to avoid their harassers, others quit because of dissatisfaction with how employers responded to their reports of harassment.

Rachel, who worked at a fast food restaurant, told us that she was “just totally disgusted and I quit” after her employer failed to take action until they found out she had consulted an attorney. Many women who were harassed told us that leaving their positions felt like the only way to escape a toxic workplace climate. As advertising agency employee Hannah explained, “It wouldn’t be worth me trying to spend all my energy to change that culture.”

The Implications of Sexual Harassment for Women’s Careers Critics of Donald Trump’s remarks point out that many women who are harassed cannot afford to quit their jobs. Yet some feel they have no other option. Lisa, a project manager who was harassed at work, told us she decided, “That’s it, I’m outta here. I’ll eat rice and live in the dark if I have to.”

Our survey data show that women who were harassed at work report significantly greater financial stress two years later. The effect of sexual harassment was comparable to the strain caused by other negative life events, such as a serious injury or illness, incarceration, or assault. About 35 percent of this effect could be attributed to the job change that occurred after harassment.

For some of the women we interviewed, sexual harassment had other lasting effects that knocked them off-course during the formative early years of their career. Pam, for example, was less trusting after her harassment, and began a new job, for less pay, where she “wasn’t out in the public eye.” Other women were pushed toward less lucrative careers in fields where they believed sexual harassment and other sexist or discriminatory practices would be less likely to occur.

For those who stayed, challenging toxic workplace cultures also had costs. Even for women who were not harassed directly, standing up against harmful work environments resulted in ostracism, and career stagnation. By ignoring women’s concerns and pushing them out, organizational cultures that give rise to harassment remain unchallenged.

Rather than expecting women who are harassed to leave work, employers should consider the costs of maintaining workplace cultures that allow harassment to continue. Retaining good employees will reduce the high cost of turnover and allow all workers to thrive—which benefits employers and workers alike.

Heather McLaughlin is an assistant professor in Sociology at Oklahoma State University. Her research examines how gender norms are constructed and policed within various institutional contexts, including work, sport, and law, with a particular emphasis on adolescence and young adulthood. Christopher Uggen is Regents Professor and Martindale chair in Sociology and Law at the University of Minnesota. He studies crime, law, and social inequality, firm in the belief that good science can light the way to a more just and peaceful world. Amy Blackstone is a professor in Sociology and the Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center at the University of Maine. She studies childlessness and the childfree choice, workplace harassment, and civic engagement.

The 2017 Super Bowl was an intense competition full of unexpected winners and high entertainment value. Alright, I didn’t actually watch the game, nor do I even know what teams were playing. I’m referring to the Super Bowl’s secondary contest, that of advertising. The Super Bowl is when many companies will roll out their most expensive and innovative advertisements. And this year there was a noticeable trend of socially aware advertising. Companies like Budweiser and 84 Lumber made statements on immigration. Airbnb and Coca-Cola celebrated American diversity. This socially conscious advertising is following the current political climate and riding the wave of increasing social movements. However, it also follows the industry’s movement towards social responsibility and activism.

One social activism Super Bowl commercial that created a significant buzz on social media this year was Audi:

The advertisement shows a young girl soapbox racing and a voiceover of her father wondering how to tell her about the difficulties she is bound to face just for being female. This commercial belongs to a form of socially responsible advertising often referred to as femvertising. Femvertising is a term used to describe mainstream commercial advertising that attempts to promote female empowerment or challenge gender stereotypes.

Despite the Internet’s response to this advertisement with a sexist pushback against feminism, this commercial is not exactly feminist. While at its core this advertisement is sending a fundamentally feminist argument of gender equality and fair wages, it feels disempowering to have a man explain sexism. It feels a little like “mansplaining” with moments reminiscent of the male “savior” trope. There is also a very timid relationship between the fight for gender equality and the product being sold. The advertisement is attempting to associate Audi with feminist ideals, but the reality is that with no female board members Audi is not exactly practicing what they preach. There are many reasons why ‘femverstising’ in general is problematic (not including contested relationship between feminism and capitalism). Here I will point out three problems with this new trend of socially ‘responsible’ femvertising.

1. The industry

The advertising industry is not known for its diversity nor is it known for its accurate representation women. So right away the industry doesn’t instill confidence in those hoping for more socially aware and diverse advertising. The way advertising works is to promote a brand identity by drawing on social symbols that make products like Channel perfume a signifier of French sophistication and Marlboro cigarettes an icon of American rugged masculinity. Therefore companies are selling an identity just as much as the product itself, while corporations that employ feminist advertising are instead appropriating feminist ideologies.

They are appropriating not social signifiers of an idealized lifestyle, but rather the whole historical baggage and gendered experiences women. This appropriation at its core is not for social progress and empowerment, but to sell a product. The whole industry functions by using these identities for material gain. As feminism becomes more popular with young women, it then becomes a profitable and desirable identity to implement. The whole concept is against feminist ideology because feminism is not for sale. Using feminist arguments to sell products may be better than perpetuating gender stereotypes but it is still using these ideologies like trying on a new style of dress that can be taken off at night rather than embodying the messages of feminism that they are borrowing. This brings us to the next point.

2. Sometimes it’s the Wrong Solution

Lets consider Dove, the toiletries company that has gained a fair amount of notoriety for their social advertising and small-scale outreach programs for women and girls. Their advertisements are famous for endorsing the body positive movement. But in general the connection between female empowerment and what they actually sell is weak. Which makes it feel insincere and a lot like pandering. Why doesn’t Dove just make products that are more aligned with feminist ideologies in the first place? If feminist consumers are what they want, then make feminist products. Don’t try to just apply feminist concepts as an afterthought in hopes of increasing consumer sales.

Dove is a beauty company that is benefiting from products that are aimed at promoting a very gendered ideal of beauty. The company itself is part of the problem so its femvertising makes me feel like Dove (and their parent company Unileaver) is trying to deny that they are playing a huge role in the creation of these stereotypes that they are claiming to be challenging. If you want to really empower women then don’t just do it in your branding start with the products you are making, examine your business model, and challenge the industry as whole. Feminist concepts should run through the entire core of your business before you try to sell it to your consumers. We don’t need feminist advertising, we need a system that is not actively continuing to increase a gender divide where women are meant to be beautiful and expected to purchase the beauty products that Dove sells. Using feminist inspired advertising doesn’t solve this underlying core problem it just masks it. Femvertising therefore is often the wrong solution, or really not even a solution at all.

3. Femvertising shouldn’t have to be a term

We really shouldn’t be in a situation where all advertising is so un-feminist and so degrading towards women that there is a term for advertising that simply depicts women as powerful. When the bar is set so low we shouldn’t praise companies for doing the minimum required to represent women both accurately and positively. We should be holding our advertising, media, and all other forms of visual representation to much higher standards. Femvertising shouldn’t be a thing because we shouldn’t have to give a term to what responsible advertising agencies should be aiming for when they represent women.

So as to not leave you on a depressing and negative note, here are three advertisements that should be acknowledged for actively challenge the norms:

_____________

Nichole Fernández is a PhD candidate in sociology at the University of Edinburgh specializing in visual sociology. Her PhD research explores the representation of the nation in tourism advertisements and can be found at www.visualizingcroatia.com. Follow Nichole on twitter here.

So, Star Wars is out with a new movie and instead of pretending female fans don’t exist, Disney has decided to license the Star Wars brand to Covergirl. A reader named David, intrigued, sent in a two-page ad from Cosmopolitan for analysis.

What I find interesting about this ad campaign — or, more accurately — boring, is its invitation to women to choose whether they are good or bad. “Light side or dark side. Which side are you on?” it asks. Your makeup purchases, apparently, follow.

This is the old — and by “old” I mean ooooooooold — tradition of dividing women into good and bad. The Madonna and the whore. The woman on the pedestal and her fallen counterpart. Except Covergirl, like many cosmetics companies before that have used exactly the same gimmick, is offering women the opportunity to choose which she wants to be. Is this some sort of feminist twist? Now we get to choose whether men want to marry us or just fuck us? Great.

But that part’s just boring. What’s obnoxious about the ad campaign is the idea that, for women, what really matters about the ultimate battle between good and evil is whether it goes with her complexion. It affirms the stereotype that women are deeply trivial, shallow, and vapid. What interests us about Star Wars? Why, makeup, of course!

If David — who also noted the inclusion of a single Asian model as part of the Dark Side — hadn’t asked me to write about this, I probably wouldn’t have. It feels like low hanging fruit because it’s just makeup advertising and who cares. But this constant message that women are genuinely excited at the idea of getting to choose which color packet to use as some sort of idiotic contribution to a battle of good versus evil is corrosive.

Moreover, the constant reiteration of the idea that we are thrilled to paint our faces actually obscures the fact that we are essentially required to do so if we want to be taken seriously as professionals, potential partners or, really, valuable human beings. So, not only does this kind of message teach us not to take women seriously at all, it hides the very serious way in which we are actively forced to capitulate to the male gaze — every. damn. day. — and feed capitalism while we’re at it.

This ad isn’t asking us if we want to be on the dark side or the light side. It’s asking us if we want to wear makeup or wear makeup. It’s not a choice at all. But it sure does make subordination seem fun.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

A new submission inspires me to re-post this great collection of public resistance to advertisements that objectify women.

Adding commentary to the ubiquitous images that surround us can help us to notice, even if just temporarily, that our environment is toxic to our ability to think of all people as full and complete humans. Here are some inspiring examples.

1. An unknown artist pastes the photoshop toolbar on H&M posters in Germany (thanks Dmitriy T.C. and Alison M.).

2. Toban B. (a prolific SocImages contributor, by the way) sent us a set of photographs. These were snapped in Seattle, Washington by Jonathan McIntosh:

3. Commentary on a Special K. ad in Dublin, sent in by Tara C. (Broadsheet).

Text:

Hey there Special-K Lady.

I know you think I should diet

So I can be slim just like you.

thing is, I think I look pretty fabulous

Just the way I am

Also, Special-K tastes like cardboardso piss off

4. This one was written on by a teenage girl in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. It reads: “I’m sick of sexually tinted images.”

5. Tricia V. sent us an example of this kind of resistance in Haiti. The billboard below is in for a brand of beer called Prestige. Tricia writes: “The writing [along the bottom of] the billboard says “Ko O+ pa machandiz” which translates as ‘Women’s bodies are not merchandise.'” She was impressed at the effort exerted to climb up and write across a full-sized billboard.

6. Ang B. snapped this photo in Madison, Wisconsin:

7. Sasha Albert saw this comment written on a “please excuse our construction” sign at her gym. Someone else had already written: “WEIRD retouching. Give us a real, healthy, normal woman!” Read more at About Face.

See also: my mom has a phd in math. For a classic example, see “If it were a lady, it’d get its bottom pinched.” For an example of backlash to public anti-sexist messages, see this post on defending privilege (trigger warning).

Cross-posted at Ms. Sources: here, here, and here.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Recently David Gianatasio at AdWeek wrote an analysis of the sudden rise in the sexual objectification of men in advertising. It seems to have been spurred by the wild popularity of the Old Spice character introduced in 2010, The Man Your Man Could Smell Like. Gianatasio calls it “hunkvertising.” Indeed, rippling abdominal muscles suddenly seem to be everywhere.

Gianatasio interviewed me for the piece and I had two thoughts. First, because the ads are so tongue-in-cheek, they didn’t seem to be acknowledging and validating women’s sexual desire, so much as mocking it. “It’s funny to us to think of women being lustful,” I told Gianatasio, “because we don’t really take women’s sexuality very seriously.” In this way, the joke affirms the gender order because the humor depends on us knowing that we don’t really objectify men this way and we don’t really believe that women are the way we imagine men to be.

Second, objectifying men alongside women certainly isn’t progress. There’s the old critique that, if it is equality, it’s not the kind we want. But, more importantly, the forces behind this so-called equality have nothing to do with justice. Gianatasio generously gave me the last word:

I wouldn’t call it equality — I’d call it marketing, and maybe capitalism. Market forces under capitalism exploit whatever fertile ground is available. Justice and sexual equality aren’t driving increasing rates of male objectification — money is.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lindy West for the win at Jezebel, asks what’s so sexualizing about calling a child’s costume “naughty.” The costume below was widely criticized for sexualizing little girls, but West nicely observes that there is a non-sexual, child-related meaning to the word naughty. You know, being bad. The non-sexual version of bad. Doing something you’re not supposed to do. A non-sexual thing. You know what I mean! West writes:

Sure, naughty has had sexual connotations as far back as the mid-19th century, but it’s been used to describe disobedient kids since the goddamn 1600s. So why did we let hornay college chicks hijack the word in all its forms? Why can’t children be naughty anymore?

It’s a great question.

The instinct that “naughty” means “bad and sexy” probably stems in part from our Puritanical roots. Today it gets tied up with the infantilization of women and the notion that women should be cute like girls. Add the rampant sexualization at Halloween, including costumes in which women dress up like little girls dressed up like sexy adult women. It’s hard to see how one could avoid interpreting this “naughty leopard” as an example of the sexualization of little girls.

Nevertheless, West is right. The biggest problem with this costume’s title is that it includes the word “leopard.” Because that’s just false advertising. It doesn’t say sexy leopard and the dress — I’ll stop calling it a costume now — is not particularly sexualizing.

West calls for change:

Why don’t we send “naughty” back from whence it came—into the realm of wedgies and spitballs and pies cooling on the windowsill with bites taken out of them!? It’s time, people. You know it is. Take Back the Naughty. For the children.

And for the grown ups, too, who are tired of the idea that being a sexual person makes us bad, bad girls and boys.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.