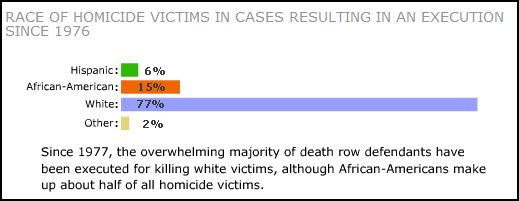

“[H]olding all other factors constant,” Amnesty International summarizes, “the single most reliable predictor of whether someone will be sentenced to death is the race of the victim.”

Originally posted in 2010. Re-posted in solidarity with the African American community; regardless of the truth of the Martin/Zimmerman confrontation, it’s hard not to interpret the finding of not-guilty as anything but a continuance of the criminal justice system’s failure to ensure justice for young Black men.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.