If you want to know who to thank for Doug Jones winning in Alabama – you can thank Black Women. #AlabamaSenateElection pic.twitter.com/8h5kfEbyJt

— UltraViolet (@UltraViolet) December 13, 2017

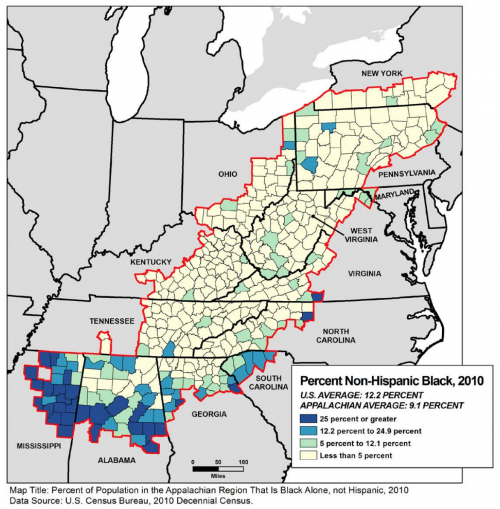

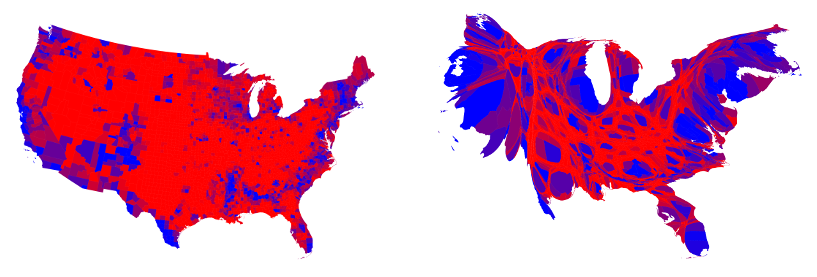

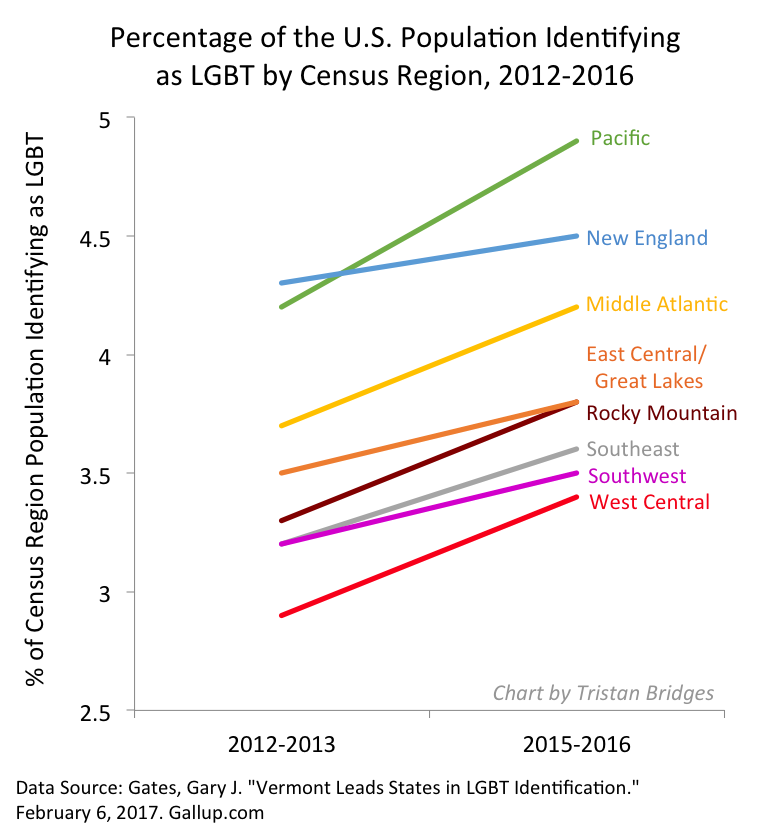

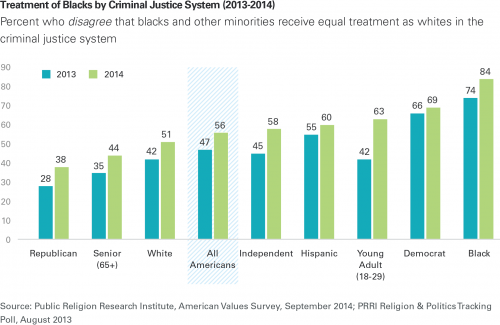

Over the last few weeks, commentary about alleged sexual predator Roy Moore’s failure to secure a seat in the U.S. Senate has flooded our news and social media feeds, shining a spotlight on the critical role of Black women in the election. About 98% of Black women, comprising 17% of total voters, cast their ballots for Moore’s opponent Doug Jones, ensuring Jones’s victory. At the same time, commentators questioned the role of White women in supporting Moore. Sources estimate that 63% of White women voted for Moore, including the majority of college-educated White women.

Vogue proclaimed, “Doug Jones Won, but White Women Lost.” U.S. News and World Reports asked, “Why do so many White women vote for misogynists?” Feminist blog Jezebel announced succinctly: “White women keep fucking us over.” Fair enough. But we have to ask, “What about Black and White men?” The fact that 48% of Alabama’s voting population is absent from these conversations is not accidental. It’s part of an incomplete narrative that focuses solely on the impact of women voters and continues the false narrative that fixing inequality is solely their burden.

Let’s focus first on Black men. Exit poll data indicate that 93% of Black men voted for Jones, and they accounted for 11% of the total vote. Bluntly put, Jones could not have secured his razor-thin victory without their votes. Yet, media commentary about their specific role in the election is typically obscured. Several articles note the general turnout of Black voters without explicitly highlighting the contribution of Black men. Other articles focus on the role of Black women exclusively. In a Newsweek article proclaiming Black women “Saved America,” Black men receive not a single mention. In addition to erasing a key contribution, this incomplete account of Jones’s victory masks concerns about minority voter suppression and the Democratic party taking Black votes for granted.

White men comprised 35% of total voters in this election, and 72% of them voted for Moore. But detailed commentary on their overwhelming support for Moore – a man who said that Muslims shouldn’t serve in Congress, that America was “great” during the time of slavery, and was accused of harassing and/or assaulting at least nine women in their teens while in his thirties – is frankly rare. The scant mentions in popular media may best be summed up as: “We expect nothing more from White men.”

As social scientists, we know that expectations matter. A large body of work indicates that negative stereotypes of Black boys and men are linked to deleterious outcomes in education, crime, and health. Within our academic communities we sagely nod our heads and agree we should change our expectations of Black boys and men to ensure better outcomes. But this logic of high expectations is rarely applied to White men. The work of Jackson Katz is an important exception. He, and a handful of others have, for years, pointed out that gender-blind conversations about violence perpetrated by men, primarily against women – in families, in romantic relationships, and on college campuses – serve only to perpetuate this violence by making its prevention a woman’s problem.

The parallels to politics in this case are too great to ignore. It’s not enough for the media to note that voting trends for the Alabama senate election were inherently racist and sexist. Pointing out that Black women were critically important in determining election outcomes, and that most White women continued to engage in the “patriarchal bargain” by voting for Moore is a good start, but not sufficient. Accurate coverage would offer thorough examinations of the responsibility of all key players – in this case the positive contributions of Black men, and the negative contributions of White men. Otherwise, coverage risks downplaying White men’s role in supporting public officials who are openly or covertly racist or sexist. This perpetuates a social structure that privileges White men above all others and then consistently fails to hold them responsible for their actions. We can, and must, do better.