Controversy erupted in 2014 when video of National Football League (NFL) player Ray Rice violently punched his fiancé (now wife) and dragged her unconscious body from an elevator. Most recently, Deadspin released graphic images of the injuries NFL player Greg Hardy inflicted on his ex-girlfriend. In both instances, NFL officials insisted that if they had seen the visual evidence of the crime, they would have implemented harsher consequences from the onset.

Why are violent images so much more compelling than other evidence of men’s violence against women? A partial answer is found by looking at whose story is privileged and whose is discounted. The power of celebrity and masculinity reinforces a collective desire to disbelieve the very real violence women experience at the hands of men. Thirteen Black women collectively shared their story of being raped and sexually assaulted by a White police officer, Daniel Holtzclaw, in Oklahoma. Without the combined bravery of the victims, it is unlikely any one woman would have been able to get justice. A similar unfolding happened with Bill Cosby. The first victims to speak out against Cosby were dismissed and treated with suspicion. The same biases that interfere with effectively responding to rape and sexual assault hold true for domestic violence interventions.

Another part of the puzzle language. Anti-sexist male activist Jackson Katz points out that labeling alleged victims “accusers” shifts public support to alleged perpetrators. The media’s common use of a passive voice when reporting on domestic violence (e.g., “violence against women”) inaccurately emphasizes a shared responsibility of the perpetrator and victim for the abuser’s violence and generally leaves readers with an inaccurate perception that domestic violence isn’t a gendered social problem. Visual evidence of women’s injuries at the hands of men is a powerful antidote to this misrepresentation.

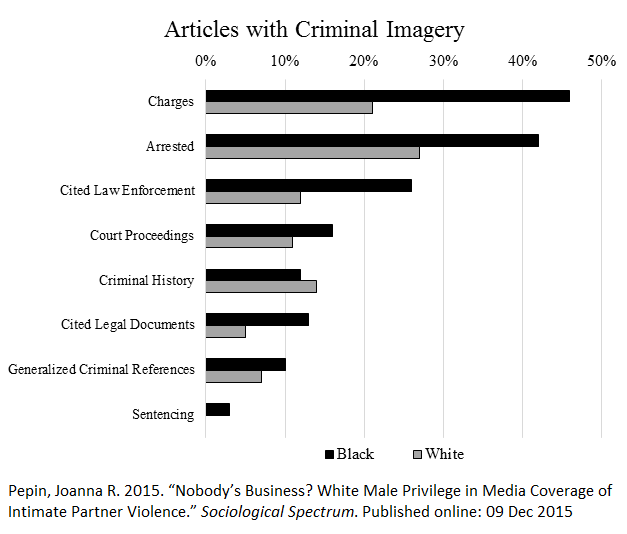

In my own research, published in Sociological Spectrum, I found that the race of perpetrators also matters to who is seen as accountable for their violence. I analyzed 330 news articles about 66 male celebrities in the headlines for committing domestic violence. Articles about Black celebrities included criminal imagery – mentioning the perpetrator was arrested, listing the charges, citing law enforcement and so on – 3 times more often than articles about White celebrities. White celebrities’ violence was excused and justified 2½ times more often than Black celebrities’, and more often described as mutual escalation or explained away due to mitigating circumstances, such as inebriation.

Data from an analysis of 330 articles about 66 Black and White celebrities who made headlines for perpetrating domestic violence (2009-2012):

Accordingly, visual imagery of Ray and Hardy’s violence upholds common stereotypes of Black men as violent criminals. Similarly, White celebrity abusers, such as Charlie Sheen, remain unmarked as a source of a social problem. It’s telling that the public outcry to take domestic violence seriously has been centered around the NFL, a sport in which two-thirds of the players are African American. The spotlight on Black male professional athletes’ violence against women draws on racist imagery of Black men as criminals. Notably, although domestic violence arrests account for nearly half of NFL players’ arrests for violent crimes, players have lower arrest rates for domestic violence compared to national averages for men in a similar age range.

If the NFL is going to take meaningful action to reducing men’s violence against women, not just protect its own image, the league will have to do more than take action only in instances in which visual evidence of a crime is available. Moreover, race can’t be separated from gender in their efforts.

Joanna R. Pepin a PhD candidate in the Department of Sociology at the University of Maryland. Her work explores the relationship between historical change in families and the gender revolution.

In his speech accepting the Republican nomination for President, Donald Trump

In his speech accepting the Republican nomination for President, Donald Trump