I’d hope that someone who has written a book about “What Shapes Our Fortunes” would have had Sociology 101 where he would have learned the fundamentally different ways that income and wealth work in our economy. But apparently not.

In Rags to Riches to Rags Again, Mark Rank writes that because of a great deal of turbulence in household earning over a lifetime “we have much more in common with one another than we dare to realize.”

One of the reasons for such fluidity at the top is that, over sufficiently long periods of time, most American households go through a wide range of economic experiences, both positive and negative. Individuals we interviewed spoke about hitting a particularly prosperous period where they received a bonus, or a spouse entered the labor market, or there was a change of jobs. These are the types of events that can throw households above particular income thresholds.

Ultimately, this information casts serious doubt on the notion of a rigid class structure in the United States based upon income. It suggests that the United States is indeed a land of opportunity, that the American dream is still possible — but that it is also a land of widespread poverty. And rather than being a place of static, income-based social tiers, America is a place where a large majority of people will experience either wealth or poverty — or both — during their lifetimes.

All together now: Income, that comes in *household* paychecks, regardless of how many earners are contributing to that household income, is not wealth. Wealth is how much money a household has in the bank and in investments and the assets they own, like real estate, businesses, land, cars, boats, and planes.

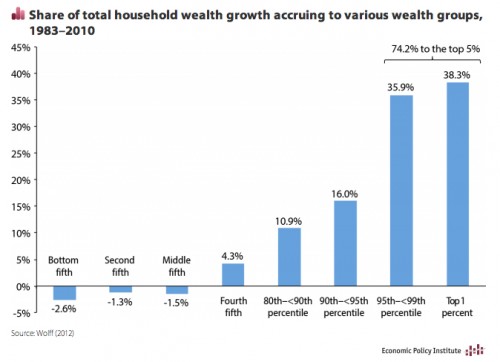

Wealth inequality is much greater than income inequality. It looks like this:

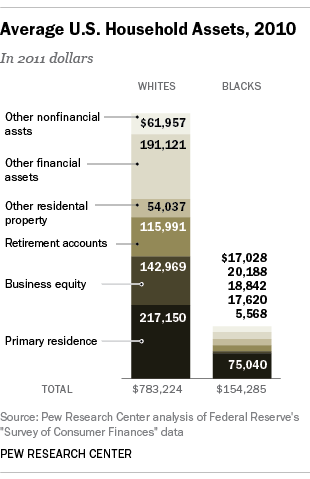

And breaking it down by race:

It is no small thing for any household to attain an annual income of a million dollars for even one year.

But it is an entirely different experience to have enough wealth that one can no longer worry about income at all, can work the tax system to mask enormous amounts of income, can essentially withdraw from everyday contact with everyday Americans, can use one’s wealth to leverage political and economic power, and can know that the children in one’s household will never, ever want for a thing.

The “1%” was never about income alone.

Jane Van Galen, PhD, is a professor of education at the University of Washington, Bothell. Her research focus is on socioeconomic class, education, and digital media. She writes for Education and Class, where this post originally appeared.

Comments 15

Yay? – Bridget Magnus and the World as Seen from 4'11" — July 3, 2014

[…] course there’s bad news hidden too: average workweek overall was 34.5 hours; wages aren’t up; when you include the underemployed and discouraged workers, unemployment looks […]

Bill R — July 3, 2014

Great post, thanks.

I would further argue that the portion of Net Worth with liquidation and investment potential is the true measure of wealth. That would be your Pew Consumer Financial data LESS primary residence and personal possessions (cars and such) LESS Liabilities, like taxes and loans.

I'll guess that you can easily cut $350,000 off the Whites to get to my number and even then it seems high to me. I have a hard time believing the "average" (mean?) Adjusted Net Worth is above 400,000.

Also, note that the real deep poverty in the US is best measured geographically and it's where its ALWAYS been--in the red/southern states sans Florida. Not a pretty picture down there.

Dan — July 3, 2014

On the Cosby show, when Claire Huxtable was asked by her daughter if they were rich (she was a lawyer, and her husband a doctor), she said, "No, we work for our money. Rich people have their money work for them." I always thought that was a good distinction.

Shannon Margolis — July 4, 2014

A priori, producers and consumers of Sociological Imagination are more informed on the associated implications of wealth and income versus Mark Rank lack of "Sociology 101 where he would have learned the fundamentally different ways that income and wealth work in our economy"

What do we know about the target audience of Rags to Riches to Rags, and for what audience does Mark Rank write?

For me the important question is does the author provide a proper context for readers to understand the graphical data presented, because honestly just looking at the two graphics I am left with lots of questions, including how does breaking this down by race provide additional insight (not to say that it couldnt be valuable, its just not clear from this post), I am also concerned the graphs and related excerpt only acts to confirms pre-existing notions and bias - are there other examples of potential for incorrect inference in the book?

If The author's self education helps a less informed audience with the appropriate context in which to grapple with the nature of inequality ( like the significance of access to resources, and the understanding that access once denied has compounding multi-generational effects.) - its a win for all. Not great would be some Bell Curve type logic to explain inequality...

Personally, I am not holding my breath that an author that includes statements like "the American dream is still possible" will provide mind blowing discourse on the nature of inequality - but I am always hopeful for a surprise :-)

Un-equality in income growth | Conrad Kotze — July 4, 2014

[…] INCOME IS A POOR MEASURE OF AMERICAN INEQUALITY […]

Mr. S — July 4, 2014

This is exactly why I'm against income tax hikes that supposedly "soak the rich." My wife and I land in the top 10% of household income, but the student debt on our balance sheet makes us decidedly not wealthy.

I should mention, though, there's a clear problem with analyzing statistical brackets vs. flesh and blood individuals. It's completely unsurprising that people in the top 1% accrued a lot of wealth since 1983. If they hadn't, they probably would be classified in the top 1%. "Rich people accumulated wealth" is hardly earth-shattering.

Guest — July 4, 2014

I don't think the "average" chart is a fair or accurate overview of the white vs black distribution. If most of the top 5% are white it really skews the picture for all the white people by averaging that in. I doubt the "average" white person has $150 in business equity. This statement alone seems to assume that every white person owns their own business as well as rental property or 2nd homes. Granted those items are included on the black graph as well but in lower #s. My point is that you shouldn't include something that the "average" person doesn't even have in order to show a white / black disparity. It's sort of like saying because there are more Asians in the world than anyone else, that the "average" person is then at least 20% Asian.

guest — July 5, 2014

I think the important part of the book the author stresses is that socio-economic status is not stagnant but rather quite dynamic. Some may have the notion that there are a fixed group of Astors , Mellons, and Rockefellers that just sit around all day and wait for their dividend checks. The amount of mobility (up and down)in the top 1% and even the top 10% is very significant. So many who where part of the 1% are no longer part of that class. Wealth is not distributed, it is earned and accumulated, there are many who earn a middle or upper middle class income but "have" substantial assets. I would be interested in seeing data regarding recent immigrants, especially from India and South Korea, and see how they have fared in the last generation or so.

Mark H Black — February 28, 2023

I've always dreamed of making a lot of money. It annoys me that there are so few good jobs in my city. All jobs are low paying. That's why I decided to trade. It doesn't take long, I'm confident that everything will be fine with my money. This is my chance to live better.

Grey_Morgan — February 28, 2023

I think that adding real value to society is important, but people need to worry about themselves first. Otherwise, their financial situation may go downhill, and that's it. Personally, I've been trading stocks for a while with https://www.koyfin.com/compare/yahoo-finance-alternative/, and I can say that profit is the main reason I do that, and I'm pretty sure that for the most people, it's their major priority as well