Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

Back in June, Mitt Romney said:

I want to make sure that we keep America a place of opportunity, where everyone… get[s] as much education as they can afford

After all, Mitt got as much education as he (his parents, really) could afford, so he thought it best if everyone had that same opportunity.

Opportunity – How much is that in American money?

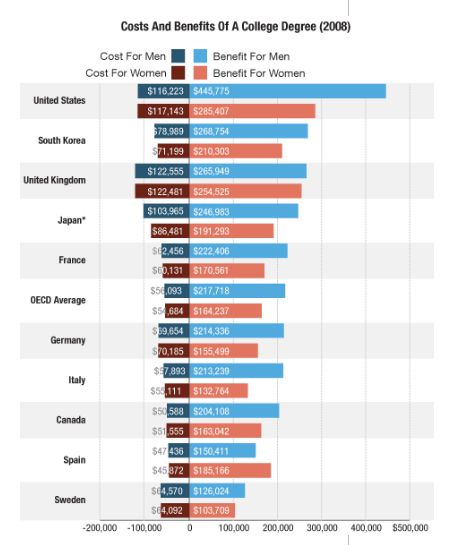

Yesterday, Planet Money posted this graph showing the costs and benefits of a college education in several countries.

The title of the post summarizes the interpretation of the college-educated folks at Planet Money:

“College Costs More In America, But The Payoff Is Bigger”

But what if you look at the data from the other side? Here’s the half-empty-glass title:

“College in the US Costs a Lot, and If You Can’t Afford It, You’re Really Screwed”

…or words to that effect.

What the chart seems to show is inequality — specifically, the inequality between the college educated and everyone else. In advanced economies, like the those of the countries in the chart, education is important. But some of those countries, like the Scandinavian countries, have reduced the income sacrificed by non-college people relative to the college educated. Other countries favor a more unequal distribution of income.

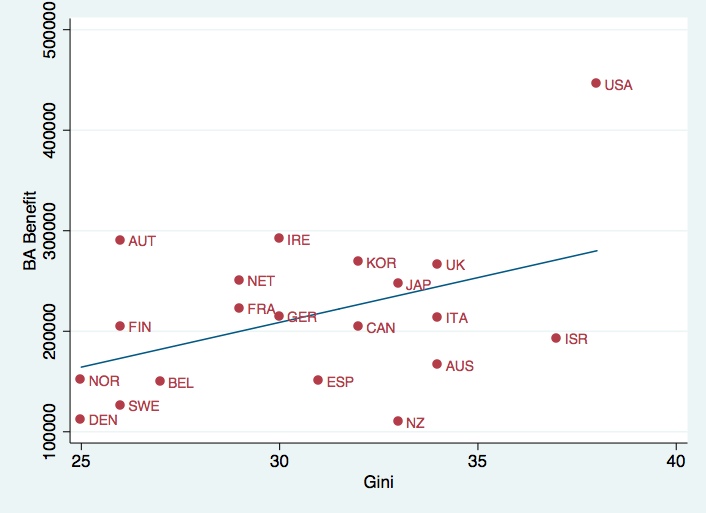

To look a little closer, I looked at the relationship between the payoff of a BA degree for men and a country’s Gini coefficient, a measure of inequality. I used the ten countries in the Planet Money chart and added another ten OECD countries.

The correlation is 0.44. The US is the clear outlier. In the land of opportunity, if you’re a male, either you pay the considerable price of going to college, or you pay the price for not going to college.

With this inequality come the kinds of social consequences that Charles Murray elaborates in his latest book about non-educated Whites — disability, divorce, demoralization, death.

—————————

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.