Last week I posted the results of a survey that found that many beneficiaries of government programs don’t recognize themselves as participating in a federal program at all. For instance, 60% of respondents who have written off their mortgage interest on their taxes didn’t see that as a government benefit or themselves as program beneficiaries. Basically, programs and policies that are disproportionately used by the middle- and upper-classes are taken for granted. I wrote,

…allowing you to write off mortgage interest (but not rent), or charitable donations, or the money you put aside for a child’s education, are all forms of government programs, ones that benefit some more than others. But the “submerged” nature of these policies hides the degree to which the middle and upper classes use and benefit from federal programs.

Brian McCabe, over at FiveThirtyEight, recently wrote a post about who benefits from the mortgage interest tax deduction program, which remains enormously popular among the general public. McCabe says,

Commentators often talk about the mortgage interest deduction as a prized middle-class benefit that enables households to achieve the American dream of homeownership. But despite their strong support for the deduction, middle-class Americans are not the primary beneficiaries of this federal tax subsidy.

If you aren’t familiar with the program, basically when you’re doing your taxes, you are allowed to reduce your taxable income by subtracting the amount you paid in mortgage interest that year. Home ownership isn’t treated equally — the tax deduction is worth more as the price of the home, and thus the amount of interest paid, goes up. McCabe points out that in 2009, this program meant that the federal government took in about $80 billion less than it would have otherwise, making it one of the most expensive tax policies and the single most expensive deduction offered to homeowners (much more than deductions for putting in energy-efficient windows, etc.).

But this expensive program is disproportionately used by relatively wealthy individuals. For instance, about a quarter of taxpayers making $40,000 – 50,000 a year claim the deduction, while over 75% of those making above $100,000 a year do:

The differences in usage is partly because the wealthy are more likely to own* homes. In addition, those with lower incomes generally buy cheaper houses and often find that they reduce their taxable income so little by writing off the mortgage interest that they’re better off taking the standard tax deduction than to itemize.

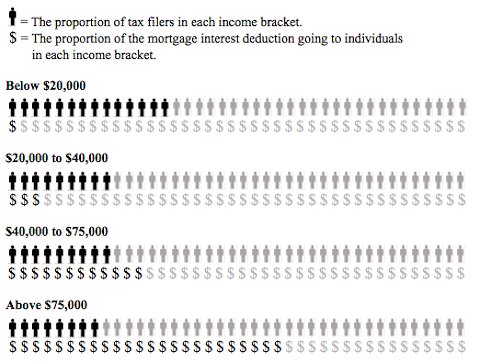

Because wealthier individuals are more likely to use the program at all, and when they do, generally have more mortgage interest to deduct, the benefits of the program go disproportionately to those with higher incomes. This image shows the proportion of all tax filers that fall into each income category, and the proportion of the total tax deduction benefit that goes to each category:

This is similar to what we see with farm subsidies: while small- and mid-sized farms benefit, the money spent on the program disproportionately goes to the largest farms. The mortgage interest deduction program is discussed as a method for helping the middle-class achieve the American Dream of homeownership. And certainly it does make home ownership more attractive to many middle- and lower-income individuals. But it overwhelmingly benefits upper-income home buyers, at a significant loss of tax income for the federal government.

* On a side note, I find it odd that we say someone “owns” their home when they owe a mortgage on it. The second I signed a mortgage last year, I entered the much-praised category of the home-owning citizen. Yet as my mortgage-hating farm family has made me very aware, I’m not even close to truly owning my home at this point; I’m more of a special category of rent-to-own resident whose landlord is the bank or mortgage company.

Comments 24

Yrro Simyarin — July 18, 2011

The real beneficiaries, of course, are the banks whose mortgage interest is being partially subsidized by the government. Or there would be a deduction just for owning a house instead of on paying interest for it.

Butter — July 18, 2011

I'm not from the US, so I was wondering if you get to deduct interest on more than one home? If you do, then it definitely would be more of a benefit to wealthy landlords who own serveral properties.

Who Benefits From the Mortgage Interest Program; Chicago “Zero Tolerance” Rules; And More « Welcome to the Doctor's Office — July 18, 2011

[...] WHO BENEFITS FROM THE MORTGAGE INTEREST PROGRAM? [...]

Shawn Blankinship — July 18, 2011

The tax advantage of buying a home artificially inflates the prices of real estate. While the tax break sounds appealing, this policy increases the house prices across the board.

Mortgages are problematic in many ways - opening up the real estate market to those unable to pay their monthly payments was a disaster that caused the recent financial crisis. Here's a link talking about modern mortgages, and their perils: http://freelyalive.com/2011/07/03/modern-death-pledge/

Anonymous — July 19, 2011

Wow, I just bought I house last week, and I had forgotten about this tax write-off. (I guess that's what happens when you get focused on house shopping.) I am, however, more conscious that your average American about government assistance, at least when it comes to college loans. What I don't get, it why so many (Often +middle class) people (including a close family member of mine) look down upon *some* government assistance programs, but not others... sure YOU'RE getting a tax break from X but when [my very close friend of 12 years] receives WIC or food stamps or section 8 housing or any of the other "lower income" benefits, I get hear to hear them bashed like they're immoral for "taking money away from hard working Americans." And yes, she's sees herself as "better" than "them." Is this economic privilege, because whatever it is, I never want to fall into these lines of thinking.

SB — July 19, 2011

"I’m not even close to truly owning my home at this point; I’m more of a

special category of rent-to-own resident whose landlord is the bank or

mortgage company."

Indeed. It is funny how we are praised for "owning our own homes" when in fact we just have really, really expensive rent for a long time that if we don't pay, ruins our credit for a long time. Rent-to-own is a most excellent term instead!

renee — July 19, 2011

To put a finer point on it: everyone who benefits from the mortgage interest deduction lives in subsidized housing. The deduction is the single largest housing subsidy program our government operates, and, as you point out, it goes primarily to upper-middle-class and rich people.

Ed — July 19, 2011

The home I owned when I was married was (is) a small one, in bad shape when we ought it. So the value of the mortgage, even with the improvement loans (officially a second mortgage), never quite produced enough interest to push us over into itemizing our deductions. We were punished for being somewhat frugal and buying no more house than we could afford. However, for at least a couple of years there was a policy where you could take $500 additional deduction (for married couples) for your mortgage interest. That was quite nice. Now I am divorced and the wife bought me out of the house.

Anonymous — July 19, 2011

Hmm... can we see the value of the mortgage deduction, as a percentage of the individual/couple taxable income? Checking my tax tables, I see that a 'head of household' making $20,000 can receive a maximum of $2406 worth of deductions, from all sources. A $5000 deduction (1/4 of gross income) is worth $750 to that person. The 'head of household' making $75000 pays tax of $13,604 before deductions; the same $5000 deduction is worth $1250, while a $18750 deduction (again, 1/4 of taxable income) is worth $4938.

Many other factors complicate the issue: "Above $75,000" is a HUGE band, including three out of the five marginal tax brackets. (Two and a half for 'Married filing jointly above $150k). The highest bracket doesn't even start until over five times that amount. (~$373k)

Yeah, the difference between $75k and paying the highest tax rate is proportionately greater than $20k and $75k.

Either break income down into octiles (bottom 1/8, second 1/8, etc.) or continue the logarithmic breakdown all the way up. (-$20k, $20k-$40k, $40k-$80k,...$640k-$1.28m, $1.28m+). There's still plenty of ways to cherry-pick the data to show the conclusion you already have about the mortgage interest deduction favoring the haves over the have nots, because it does.

Also note that it is not a government program, it is a tax cut. The distinction apparently only makes sense to the Republicans who insist that programs be cut but tax cuts remain...

Quercki — July 22, 2011

You might be interested to know that the size of the home mortgage that is deductible is capped at $1,000,000. (Lots of houses in California cost more than that--the same house in Tennesse would be about $250,000.)

http://www.irs.gov/taxtopics/tc505.html

eeka — July 23, 2011

FWIW, on the Massachusetts tax return, you can deduct your rent. It doesn't allow itemizing -- there are only a few things you can deduct, and this is one of them. Meant to equal things out for people who rent with people who have mortgages, I assume.

Mawg Land — July 26, 2011

I don't see how someone can compare a mortgage deduction to a government subsidy. The deduction reduces the amount of taxes you pay; its your money, and the government is just taking less of it; illustrated by the fact that the deduction can't exceed the amount of taxes you owe. I don't see how this compares to subsidies or any other type of government program where people or businesses receive money from the government over and above what they've paid in to it.