This is the iconic photo of Tommie Smith and John Carlos (found here) from the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. They raised their arms, wearing black gloves, in a symbol of protest against racism in the U.S. Less often noticed is that they were wearing beads to symbolize victims of lynching and went barefoot to protest the fact that the U.S. still had such extreme poverty that some people went without basics, such as sufficient clothing. Peter Norman, the Australian 2nd-place winner, grabbed a button produced by the Olympic Project for Human Rights (see below) when he found out what the other two were going to do and wore it in solidarity (if you look closely you can see that all three are wearing matching white buttons).

The reaction was immediate and negative. Carlos and Smith were stripped of their medals, ejected from the Olympic Village, and returned to the U.S. to widespread anger. In David Zirin’s book What’s My Name, Fool? Sports and Resistance in the United States (2005, Chicago: Haymarket Books), several black athletes discuss the difficulties they faced as a result of their actions. This 2003 interview with Tommie Smith covers some of the same issues.

Below is a button like the ones they were wearing. Much like we often think Rosa Parks spontaneously decided not to give up her seat on the bus (ignoring the fact that she attended training with other African Americans determined to protest inequality in the South), the assumption is often that Smith’s and Carlos’s gesture was something they decided on at the moment. In fact the Olympic Project for Human Rights, organized by Black U.S. athletes, had tried to organize an athletes’ boycott of the 1968 Olympics. When that was unsuccessful, tactics switched to making statements at the Olympics. This was part of an organized plan on the part of a number of Black athletes who were tired of representing the U.S. but being expected to stay silent about racism in the U.S.

Some of these buttons are for sale ($300 each!) on Tommie Smith’s website.

A t-shirt with the cover of the July 15, 1968, issue of Newsweek about “the angry black athlete.”

I looked for a photo of the cover itself but could not find one online. Clearly the nation was anxious about the attitudes of Black athletes even before the Olympics (in October) caused such a stir.

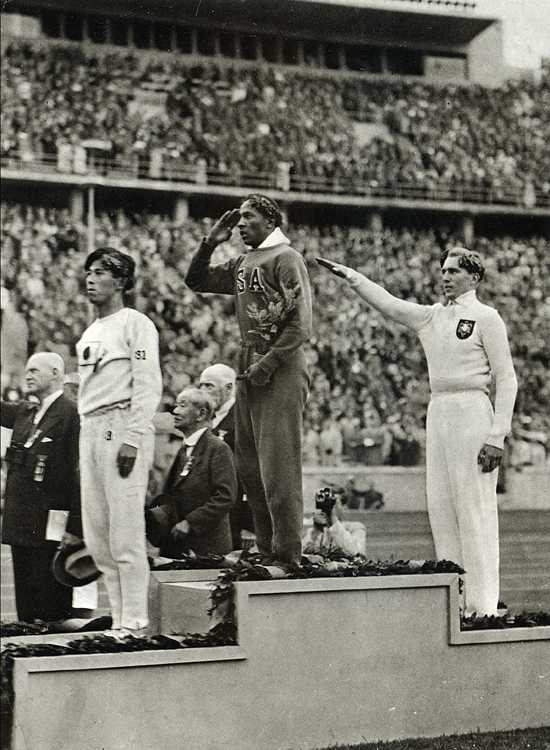

I think these images are useful in a couple of ways. I use them to undermine the idea of the individualistic protester and to bring attention to the ways Civil Rights activists organized and planned their actions. It could also be useful for discussions of politics in sports–the ways in which athletes have at times used their position to bring attention to social inequality, as well as the repercussions they may face for doing so. It might also be interesting to ask why this image caused so much furor, and how the Olympics is constructed as this non-political arena for international cooperation (a topic I cover in my Soc of Sports course). You might compare the image from the 1968 Olympics to this image (found here) from the 1936 Olympics in Germany:

Here we also see the Olympics being used to make a political statement, but in this case the athlete was not thrown out of the Olympic Village or stripped of his medals. What is the difference? Just that time had passed and attitudes toward political statements at the Olympics changed? In the 1936 pose, the athlete was showing pride in and support for his country, whereas Smith and Carlos meant their gesture as a protest of conditions in the U.S.–thus shaming their nation in an international arena (this was a major cause of the anger they faced when they returned to the U.S.–the idea that they were airing the nation’s “dirty laundry,” so to speak, for others to see). Could that be part of the difference in the reaction?

Of course, a cynical person might argue that these seemingly ungrateful, misbehaving black athletes who refused to smile and play along were being publicly punished in the media for getting “uppity” (in a time period where white Americans were also wearying of minorities’ continued demands for equality and social change).

Comments 6

Sociological Images » What We’ve Been Up To Behind Your Back (May 2009) — June 2, 2009

[...] One year ago Gwen wrote an extensive post about the 1968 Olympic medalists Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who used their medal ceremony to try to draw attention to racism and poverty in the U.S. Her post does an excellent job of describing and analyzing the protest and its aftermath. Visit it here. [...]

what is the most iconic photo? — September 30, 2010

[...] [...]

Anonymous — June 2, 2011

hgsoihoiehgoe;irhgo oigheorigho gherog gh roigh oireoi eir giuhdf hliuds bf hilu dsgri huger ihlugr iu sgrhiug dihdsf g hiuds gri hurg i hu ger hiug s hious dg ho rgs hoigr oih gresoh is ih os iho u

Anonymous — June 2, 2011

yeah i agree with all of the above statements. just a wonderful article. :D :);)

Facts Matter | Histories of Social Media, by Jonathan Salem Baskin — August 3, 2011

[...] credit: realizing the dream) Tagged with: histories of social media • jonathan salem baskin Share [...]

ladylocs69 — September 12, 2016

#TheHistoryOfAmerica THROUGHOUT THE HISTORY OF AMERICA.... WHETHER, 1637, 1808, 1927, 1968, 2016, ....EUROPEANS IN AMERICA HAVE ALWAYS MISTREATED THE PERSON OF AFRICAN DESCENT.....100 YEARS AFTER SLAVERY ENDED, SEGREGATION WAS THE LAW.... SEPARATING DIFFERENT RACES OF PEOPLE WAS THE LAW.....HOWEVER, BLACK PEOPLE REMAINED LOYAL TO AMERICA... FIGHTING IN THEIR WARS AND CLEANING UP THEIR MESS..... . PRIOR TO THE 1968 OLYMPICS...... ... BLACK AMERICA IN PARTICULAR HAD JUST WITNESSED THE ASSASSINATION OF A PEACEFUL CHRISTIAN MAN... DR. KING....AMERICA ALLOWED OTHER AMERICANS.... TO DISCRIMINATE AGAINST BLACK PEOPLE.... WHITE FOLKS SPIT ON BLACK KIDS THAT WANTED TO ATTEND SCHOOLS WITH THEM.... WHITE RACISTS AMERICAN COPS ATTACKED BLACK PEOPLE ( PEACEFUL PROTESTERS) WITH DOGS, KILLED CIVIL RIGHTS LEADERS AND JAILED OTHERS..., LYNCH MOBS FORMED .....ETC..... EVEN AFTER DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. WA ASSASSINATED IN AMERICA... BY THE HANDS OF A RACIST AMERICAN SET UP BY A RACIST FBI AGENCY......AFRICAN AMERICAN ATHLETES STILL REPRESENTED AMERICA IN THE OLYMPICS......., WOW!!!!!!! WHO DOES THAT! WE DO THAT'S WHO! THAT ALONE DESERVES RESPECT....... SO CHECK T....... WE WILL KNEEL AND PROTEST..... POVERTY IS THE CAUSE OF VIOLENCE..... WHEN U MIX THAT WITH ILLITERACY.... U HAVE A MESS........ UNTIL U HAVE BEEN OPPRESSED..... THEN, U HAVE NOTHING TO SAY.....