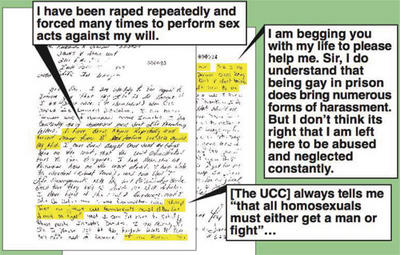

The seattle times has been following the case of michael mullen, who confessed to killing two registered sex offenders in bellingham, washington. i wrote about the murders last month, suggesting that public availability of specific addresses and offense details might be a net loss to public safety. mullen wrote a letter to reporter mike carter at the times, which (after some hand-wringing) it decided to publish online in mullen’s original hand:

“[s]hould we post the letter itself online? Most who had read it said yes. Here’s why: Reading the handwritten letter was a different experience from reading the story. It was methodical. The penmanship doesn’t change. Mullen thought out the message just as he said he had thought out the crime. If you are concerned, scared or just fascinated, you want to understand what he had to say. … “Certainly no one in his right mind would agree with vigilante Justice,” Carter said, “but people are very frustrated about how society deals with sexual predators.” He added, “the overarching sentiment (from readers) has been one of people agreeing with Mullen’s sentiments, if not his methods.”

is there a real danger that publicizing mullen’s motivations will lead people to agree with his sentiments or inspire other vigilantes? as “p.s. punk” predicted in a comment to my earlier post, mullen spins a tale of righteous slaughter and wishes to make himself a martyr. he claims that he went to “interview” the three former sex offenders living at the house, checked their IDs to confirm identification, and let one of them go after he “showed remorse or guilt.” he claims that the two he killed “blammed [sic] their victims — they showed NO remorse.”

such statements show how easily a vigilante assumes the roles of judge, jury, and executioner. i’m most interested in how his comments reveal the dark side of community notification. here’s what the confessed killer said on the subject:

“the State of Washington, like many states now lists sexual deviants on the Net. And on most of these sites it shares with us what sexual crimes these men have been caught for, and most are so sick you wonder how they can be free … In closing, we cannot tell the public so-and-so is ‘likely’ going to hurt another child, and here is his address then expect us to sit back and wait to see what child is next”

mullen clearly blames the victims for their deaths, but he also implicates institutions that make the information public (i’m sure he’ll be pointing other fingers elsewhere as we get closer to his trial). i’m working on a project now coding the information provided by each state on sex offenders and other felons. reading through the individual case records that some states post, one cannot help but see them as “sick” monsters. one sees a bad picture, a horrific description of a crime, and an address. even if the acts are decades old, there is typically little countervailing information that would help us understand their current circumstances or the extent to which they pose a threat to public safety today.