Recently, in the run-up to the 2012 presidential election, Stacey Dash—eternally youthful actress and star of the 90s classic “Clueless”—tweeted, “Vote for Mitt Romney. The only choice for your future.” The blowback, in true Twitter form, came quickly and not so nicely. Since The Society Pages is an upstanding site, I’ll spare you the most venomous responses. But a central theme was captured by a tweet from Tretista Kelverian, who joked, “You’re an unemployed black woman endorsing @MittRomney. You’re voting against yourself thrice. You poor beautiful idiot.” The sentiment behind this biting response—that black interests and Republican partisanship are fundamentally discordant—has come up in every conversation I had with an African American Republican, as well as every conversation I had with others about African American Republicans.

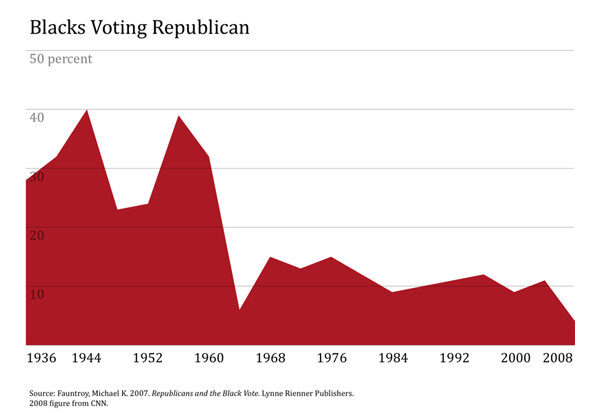

Black Republicans report feeling excluded from the African American political community, and their beliefs are often maligned as racially inauthentic. Some revel in their outsider status, provoking controversy with inflammatory statements about race and racism. Yet, for the vast majority, the charges sting. Accusations of racial betrayal hurt not only because they are insulting, but also because the “sellout” narrative fundamentally misrepresents black Republicans’ political agenda. Further, obsessing over whether African American Republicans are sellouts obscures important differences among them, particularly in regard to how they think about race and social policies. Rather than focus on whether they are “black enough,” political analysts would be better served by examining how race structures the politics of these conservatives. Once we move past the sellout question, it becomes clear that there are important racially motivated divides among African American Republicans.Given the negative reputation associated with being an African American Republican, it is not surprising that there are not that many of them. After emancipation, the overwhelming majority of black Americans supported the Republican Party. However, since the 1930s, they have been steadily withdrawing their support from the Party of Lincoln. The 1968 election, in which Nixon deployed his infamous “Southern Strategy,” garnered all-time low levels of Republican partisanship among blacks. That is, until the 2008 presidential election, when 96% of black voters cast their vote for Barack Obama, the Democratic candidate. Polling for the 2012 election reveals this isn’t likely to change.

This dramatic reversal of partisanship has left very few African Americans part of the coalition of Republican voters. Some estimates suggest only 3% of Republican voters are black: African American Republicans are rare among both black voters and Republican voters.

In spite of this rarity—or, perhaps, because of it—African American Republicans are enjoying their highest profile since the Reconstruction era. This attention extends beyond the usual big names like Condoleezza Rice, Colin Powell, and Clarence Thomas. For instance, Mia Love—the black, Mormon, small town Utah mayor who’s running for Congress—used a prime-time speaking spot to wow the audience at the Republican National Convention. Herman Cain ran a brief, high-profile campaign for the 2012 Republican Presidential nomination. And the November 2010 midterm elections saw a record number of African American Republicans running for Congress: 32 candidates made bids for office and 14 won their primaries. Only two, Allen West of Florida and Tim Scott of South Carolina, won in the general election (they became the first African American Republicans in Congress since 2003). Even pop music is in on the black Republican renaissance, with Nas and Jay-Z’s 2010 single “Black Republican.”

For such a small group, African American Republicans are everywhere, but their foray into popular culture hasn’t been a walk in the park. Alongside their white conservative counterparts, African American Republicans have gotten their share of mocking, but in their case, the humor is based in the very idea that a black person would be Republican.

Whether it results in attacking or mocking, most responses to African American Republicans are grounded in the idea that blackness is incompatible with the Grand Old Party. As a result, black conservatives are still seen as somehow “less black” because of their partisanship.

Not Just Uncle Toms

Given this context, it is surprising to find African American Republican activists expressing strong connections to other black people: they don’t see themselves as “less black.” They tell me they live in black neighborhoods, attend black churches, are members of black organizations, and work with black people. Their lives are subject to the same residential and workplace racial segregation that many African Americans experience. Unfailingly, interviewees refer to “us,” “we,” and “our community” when referencing black people. Far from being estranged from other blacks, the African American Republicans I talked to are deeply embedded in black communities.

Michael Dawson describes this feeling of connectedness as “linked fate,” and his research suggests linked fate is a key driver of African American political behavior. All participants in my research, too, express pretty high levels of linked fate, but there are also important differences in how they engage in Republican politics. African American Republicans have varied feelings about their connection to other blacks: some value it, and others find it troublesome. The fact that all of the black Republicans I talked to felt connected, but did not attach the same meaning and importance to that connection, is key to delineating their political activities.

Based on my research, African American Republicans can actually be categorized into two groups based on the centrality of race in their worldview. I call the first “raceblind.” They see racial status, and any associated discrimination, as marginal to the life experience of blacks. Instead, they believe personal choices and pathological values are responsible for racial disparities in the U.S. This is consistent with the “sellout” reputation that stigmatizes African American Republicans.

I believe the second group of black Republicans is characterized by a worldview of “racial uplift.” While not denying a role for personal responsibility, they see blacks as constrained by blocked opportunities and racism—an American structural reality that affects the lives of all African Americans. Unlike their raceblind counterparts, racial uplift African American Republicans place race at the center of their political outlook.

Both raceblind and racial uplift African American Republicans see the GOP’s policy program as the best way to meet the needs of black communities, but they define those needs in contradicting ways. Thus, variations in the perceived importance of race structures ideas about black interests and impact African Americans’ expressions of Republican partisanship. In terms of actual policy preferences, there is actually not that much difference between the two types of African American Republicans. They all support similar social and fiscal policies. They simply invoke different rhetorical strategies in support of those preferences.

Raceblind vs. Racial Uplift

Consistent with other accounts of raceblind politics, African American Republicans who can be categorized as raceblind de-emphasize the importance of race in both the causes and solutions to problems facing the black community. They work to eliminate race from their policy consideration, going so far as to suggest that racially conscious social policies are no different than Jim Crow, since both acknowledge and promote a racial distinction. For them, Republican policies are ideologically and philosophically appealing. In contrast, the racial uplift African American Republicans present social policies in light of how they affect black people. For African American Republicans who employ this framing, the appeal of traditional GOP policy positions is not tied to an abstract, ideological notion of being “right.” Rather, these policies are appealing because they are best suited to place black people on the path to middle-class success. These differences are quite stark when African American Republicans talk about specific policies.

Kevin,* like all the subjects in my study, is primarily active in state and local Republican politics. He’s an entrepreneur living outside of Atlanta, and he came to Republican politics to escape what he described as the “tiring” politics of the Democratic Party. “I just got so tired of constantly hearing the same things, but not getting any results,” he explained over coffee. “I guess I just feel like we, as black people, have to stop seeing everything in black and white. You find what you want to see. You keep looking for racism and you’ll find it soon enough. I just try to do my own thing and let my success speak for itself.” Accordingly, he values conservative economic policies based on “principles that benefit everybody,” not just narrow interest groups. His pet issue is “tax reform,” in particular repealing the inheritance tax. This tax seemed a strange canard, given that Kevin and his heirs were unlikely to ever be subject to it. But Kevin insisted it’s an issue of fairness and an ideological commitment to keeping the state out of his wallet. “What it [tax reform] does is keep us from the death tax [inheritance tax]… That keeps us from being able to transfer to our children stuff that we want to pass down to them… I think it’s a money issue period. And people try to make it into a black issue, and it’s actually a class warfare issue between the haves and the have-nots.” Consistent with this raceblind approach, Kevin sees low taxes and pro-business policies from a race-neutral, ideological perspective. When he does invoke social categories, he draws on class. In his mind, fiscally conservative policies are good for everyone.

Jason sees the benefit of low taxes differently. In our conversations, he recalled growing up in close proximity to economic depravation. Although he never lived in what he labels the “ghetto neighborhood,” he rode the bus with kids from that neighborhood. He believes such black neighborhoods suffer from a lack of investment. “Look around. You don’t see no businesses. No kind of economic development.” When Jason echoes the broader Republican call for lower taxes, he frames that support in racial uplift terms that stress the relevance of low taxes for black people. “When taxes are lower there is more money to invest back into the community. How can you support black businesses if you’re losing half of your paycheck to taxes?”

Steven, another racial uplift African American Republican, draws on similar rhetoric when discussing the benefits of conservative fiscal policies: “When taxes are low, that encourages business development and entrepreneurship in black communities. When taxes are lower, there is more money to encourage business. And that’s what we need in our communities. All these empty storefronts could be filled with black-owned companies. Black folks think high taxes are good for social programs, but we’re really shooting ourselves in the foot because it doesn’t encourage black businesses.” Steven goes so far as to juxtapose low taxes against social welfare programs; in his calculation, lower taxes will ultimately provide the more resources for black communities. For Jason, Steven, and their counterparts, lower taxes mean blacks will have more money to invest in their communities.

The raceblind/racial uplift framing tension goes beyond taxes, of course. Although support for school vouchers was almost universal among the African American Republicans I interviewed, some saw vouchers as an expression of the power of markets while others saw vouchers as giving parents control over their children’s education. Bobby deploys a raceblind framing that draws on the power of market-based reform as he describes his support for vouchers: they “force schools to compete. Once you give people choices and schools can’t count on that money, they’ll get their acts together or they’ll close.” Samuel sees vouchers through the lens of race. “You know why I love school vouchers? Because they give black parents control over their kids’ schools. It puts black parents in charge of black kids. Not some white person from the school board who doesn’t have any idea of what black children in black communities need.”

With these distinct framings of Republican policy, it would be easy to envision raceblind African American Republicans as callow, self-serving Uncle Toms and racial uplift African American Republicans as quasi-Black Nationalists down for revolution. But it would be careless to caricature raceblind African American Republicans as delusional stooges, and it would misrepresent racial uplift partisans to suggest they’re champions of social justice, calling for the overthrow of a racist social order. Even the staunchest of raceblind African American Republicans will agree that there are racist individuals and racism exists—they just don’t see much effectiveness in launching race-based political appeals. Ignoring race is seen as the best route to ensure that blacks are assimilated into mainstream American culture. And, though racial uplift African American Republicans see structural racism as a key problem facing blacks, their call to action is centered on the idea that blacks have to be responsible, individually and collectively, for their own success. This does little to call into question the institutional forces that produce racial inequality, but retains hope for an environment in which blacks can get in on the fun happening at the top of the pyramid.Re-thinking African American Republicans

Whether we see them speaking to packed stadiums at nominating conventions or on cable news pugnaciously attacking the “poverty pimps” of the Democratic Party, the picture the media paints of African American Republicans suggests they are unified in their rejection of identity politics. However, the raceblind antics of politicians like Mia Love and Herman Cain don’t tell the full story of African American Republicans. Attending to how race orients their political beliefs illuminates an important difference among African American Republicans. For raceblind African American Republicans, connection to racial identity is deep and often invoked as motivation for their partisanship, but race is deemphasized in the arena of social policy. In contrast, racial uplift African American Republicans see everything through the lens of race, but deploy their racialized worldviews in support of conservative social policy. While there is consistent support for Republican policy positions across the core of black conservatives, the motivations and justifications for those positions vary in important ways, but we can only see them when we move past trying to determine whether Republican politics and the people who engage in them can be authentically black.

In many ways, the charges of “sellout” or “Uncle Tom” reflect the anxieties of other political actors rather than the motivations of African American Republicans. So while most conversations about African American Republicans start by asking some variant of the “Are they black enough?” question, a more useful question might be “What meaning do they attach to being black?” This draws attention to the processes through which race and racial identity can be marshaled in support of a broad range of political ideologies and social policies, though this analytic shift requires an agnostic approach to any specific policy issues. In the case of African American Republicans, that means I must refrain from adjudicating the “rightness” or “wrongness” of their policy preferences. Such judgments are well beyond the scope of my research, but, more importantly, they shed little light on the processes through which race gets linked to political behavior.

So, once we’ve stopped assuming race as the “cause” of certain political behavior, we can begin to ask more expansive questions. For instance, raceblind African American Republicans enjoy much more success within the Republican Party than their racial uplift counterparts. Why? Additionally, among black conservatives, the same “levels” of racial identity can produce very different political behaviors. This suggests that a broad range of political actions can be done in the name of “black people” and demands that we direct attention to how and why racial identity—or any identity, for that matter—is brought to bear on political decisions. Time spent on considering “racial authenticity” is time that would be better spent in taking on these more analytically useful questions.Race, this is to say, is not a static category with self-evident meanings. We cannot assume the meaning of race to be consistent and constant. Indeed, recent research demonstrates that African Americans and other racial minorities vary in the extent to which their racial identities are meaningful across a range of social domains. A similar trend seems to be true in the political arena. By showing differences in the way that race structures policy framings among African American Republicans, my research urges the undertaking of questions about when and why race matters in political behavior and how racial identity gets linked to a particular political program. The relative rarity of black Republicans cannot be allowed to undermine true inquiry or excuse monolithic representations of them as somehow both unique and uniform.

Recommended Reading

Michael Dawson. 1995. Behind the Mule: Race and Class in African American Politics. Shows how, despite increasing class diversity, race is still the dominant driver of African American political behavior. Introduces the concept of “linked fate” to account for African American political unity.

Angela Dillard. 2002. Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner Now: Multicultural Conservatism in America. Focuses on the intellectual leaders of various “minority” conservative factions and offers a comparative analysis of the motivations and philosophies of conservatives that cuts across race, gender, and sexuality.

J.G. Conti, Stan Faryna, and Brad Stetson (editors). 1997. Black and Right. This collection of essays offers personal and political portraits of black conservatives in America.

Michael K. Fountroy. 2006. Republicans and the Black Vote. Provides an overview of the history of African American participation in the Republican Party.

Christopher Allan Bracey. 2008. Saviors or Sellouts: The Promise and Perils of Black Conservatism, from Booker T. Washington to Condoleezza Rice. Examines black neoconservative thinkers and politicians to explain why conservatism remains a coherent and coherent ideological alternative for African Americans today.

* All respondent names are pseudonyms.

Comments 5

Taylor Day — October 12, 2012

I think it is extremely unfair that some people are judging people of a race for liking a certain political candidate. Just because two people are the same skin tone does not mean that they have anywhere near the same political views. Sure, they may have similar social characteristics, but if that argument is made than the same could be same for people of the same gender. I don't believe how many women vote for who they do, but at the same time just because we are both women does not mean we believe the same things, even if the world thinks we should.

At the same time, there are a projected 96% of the african-american community voting for Obama. That is a significant number, which shows that their could be a relationship between race and political party, but this theory has not been tested.

David Quinn — October 30, 2012

I think that the lack of blacks in the Republican party is a very interesting phenomenon. I do not think that the Republican Party is in any way exclusive to whites. I think that the popular culture likes to claim that the Republican Party is anti-black, and only the Democratic Party cares about them. I think that both the race-blind and racial uplift Republicans have very valid reason for their conservative beliefs. It is an interesting sociological phenomenon when the larger culture seems to believe that blacks have to be in favor of entitlement programs if they truly care about their race.

The racial blind Republicans really interest me. It is good to see that some people do not view their race as the defining characteristic of their identity. They are able to put other views before their view of race. I do think that structural racism is a definite block to the social mobility of many blacks, but I do not think that the only solution to this problem is governmental programs. I think that it is good to get members of the black community to question the seemingly taken for granted belief that blacks have to be Democrats. I hope that this minority of the black community can get their views into the public discourse to get more diversity into the potential solutions to the issue of structural racism that have unjustly limited many members of the black commnity.

Jim Lawler — February 19, 2014

What has the Democratic party done for African Americans? First they suppressed and enslaved them. Then they segregated them. Then they used the "Great society" to buy votes with their group think policies used progressive taxation to hurt the working black poor jobs and the the black family.

The establishment GOP is useless. However, conservativism is a harder sell but it creates opportunity and liberty. Under the last realy lconservative President Reagan black employment, black business ownership and black professional jobs all boomed. To quote the link below: Between 1982 and 1988, total black employment increased by 2 million, a staggering sum. That meant that blacks gained 15 percent of the new jobs created during that span, while accounting for only 11 percent of the working-age population. Meanwhile, the black jobless rate was cut by almost half between 1982 and 1988. Compared that to Obama disaterous double digit unemployment record for American americans.

Link

http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/1152200/posts

The Democratic party has done a much better job of selling their soft tyranny than the GOP has done selling conservative success. The establishment GOP is clueless. Conservativism works and would help the African American community if once again given the chance.

Allison — June 15, 2015

This article was very very liberating. I, until this article, could not identify what type of black conservative or Republican I was. I had a difficult time coming to terms with race-blind, black republicans, hearing them on talk shows and reading their books and articles as they purport that some of the obvious societal racial infractions against blacks were not because of racism. That stories like Trayvon Martin were unfortunate, but that he was indeed an aggressive black male and there were other important issues going on in the world, or that race in America is an illegitimate social construct that is only in the mind of black liberals. I could not, in my soul, come to terms with the race-blind republicans, because racism indeed exists and it is not a fantasy or a bad dream that we can wake up from. It is there and every present, and denying it doesn't make the personal incident I had go away when in fact a racist white man that asked me what right do I have and what was I doing in a particular popular outdoor gear store. So I had to find middle ground. I couldn't find it until this article so thank you for that. Because we blacks are conservative, and as I believe that blacks are somewhat pathological in our thinking, yet we are still individuals, I can't ignore that race and our identity in America is still encumbered by the prominent power structure. As a black conservative, I find that I feel things collectively, yet rail against group-thinking. I want to be judge individually, yet believe collectively that blacks can change the power structure paradigm in society. And to do that, we have to be represented in all political parties. I am a race-uplifting conservative! Thank you for your article and insight.

The Divide Among Black Republicans – Orpheé Noir — September 13, 2016

[…] find evidence of this commitment in the work of Corey D. Fields, a sociologist at Stanford University. With regards to matters of race, Fields […]