To the extent that political scientists evaluate Facebook’s impact on the American political system, the verdict is that it doesn’t matter much, particularly when compared with other factors like the condition of the economy or number of combat casualties (see Andrew Lindner’s fantastic TSP essay on the subject). And this assessment might be true if we gauge impact via a direct, measurable effect on electoral outcomes. But what if Facebook impacts politics in a much broader way? Here, I look at how Facebook’s nearly ubiquitous use might change not just the outcome of the political game, but the playing field itself.

In October 2012, Facebook surpassed one billion accounts. In a 2010 blog post, its researchers reported they could predict the winning House candidate over 70% of the time, just by looking at the candidates’ “likes.” While Facebook has a vested interest in convincing the mass public that it has its “finger on the pulse” of mass culture, social scientists have a great deal of skepticism regarding its impact on the political process. As Gregory Ferenstein recently posted on TechCrunch, “if social media mattered in elections, Ron Paul would have a realistic shot at being the Republican nominee.” Indeed, one only has to compare the significant gap in Facebook page “likes” between President Obama (31,129,331 on Oct. 22, 2012) and Republican candidate Mitt Romney (10,330,215 on the same day) to their much closer positions in the polls to recognize that Facebook popularity contests aren’t directly translatable to electoral outcomes.Another key argument against Facebook’s impact on American politics is that those most likely to use Facebook are also least likely to be engaged with politics. A May 2012 Pew survey found that close to two-thirds of people in the United States reported using some form of social media and almost all of those used Facebook (Brenner 2012). When broken down by age, 86% of 18- to 29-year-olds used social networking sites. By comparison, only 34% of those 65 and older were SNS users. Since 18- to 29-year-olds are historically less likely to vote than other groups, Facebook would not appear to be very fertile soil from which to extract votes. Shoring up this idea, a recent Gallup survey affirmed that 18- to 30-year-olds were significantly less engaged in the 2012 presidential election than they were in 2008.

But Facebook can’t be blamed for the public cynicism that stems from partisan gridlock in Washington. Some argue that Facebook might be affecting politics by ushering in a new, different era of youth participation. So, though young voters might be less likely to vote in elections, Facebook users are “civically engaged” in other ways. A 2011 Pew Internet and American Life survey found that frequent Facebook users (that is, those who visited the site at least once a day) were more likely to exhibit a number of pro-civic attitudes. They were three times as likely as nonusers to believe that people could be trusted, had closer personal ties, and were more likely to receive social, emotional, and tangible support from friends. These “connected” Facebook citizens exhibited greater levels of the social capital that Robert Putnam and others see as vital to civic life, which generally means they are more likely to engage in public life than be disconnected from it.

But Facebook can’t be blamed for the public cynicism that stems from partisan gridlock in Washington. Some argue that Facebook might be affecting politics by ushering in a new, different era of youth participation. So, though young voters might be less likely to vote in elections, Facebook users are “civically engaged” in other ways. A 2011 Pew Internet and American Life survey found that frequent Facebook users (that is, those who visited the site at least once a day) were more likely to exhibit a number of pro-civic attitudes. They were three times as likely as nonusers to believe that people could be trusted, had closer personal ties, and were more likely to receive social, emotional, and tangible support from friends. These “connected” Facebook citizens exhibited greater levels of the social capital that Robert Putnam and others see as vital to civic life, which generally means they are more likely to engage in public life than be disconnected from it.

Furthermore, the same Pew survey found that frequent Facebook users were much more politically active than nonusers. These frequent users were 53% more likely to vote than nonmembers or infrequent users, 78% more likely to try to influence someone to vote, and over two and a half times more likely to attend a political meeting or rally.

So, Facebook is a vital engine for promoting civic engagement? Perhaps, but major questions of cause and correlation remain. Do civically and politically engaged people become heavy Facebook users, or does heavy Facebook use make users more politically engaged? Perhaps what matters is not how often people use Facebook, but the ways in which they engage. Scholars Moira Burke and Robert Kraut, along with Facebook researcher Cameron Marlow, have found that Facebook users increase their level of social capital when they engage in direct, person-to-person communication with Facebook friends. Similarly, social scientists Namsu Park, Kerk F. Kee and Sebastian Valenzuela have shown that students who use Facebook to socialize with friends or seek information are more likely to become engaged in politics than those who just use it for entertainment. And, in a 2009 talk, Jessica T. Feezell, Meredith Conroy, and Mario Guerrero reported that college students that belonged to a Facebook group were more engaged with politics and more likely to vote than those who were not. It appears that those who seek out political information on Facebook find it and are more likely to engage in politics that those Facebook users who don’t, but whether Facebook creates politically engaged citizens is very different matter.

Evgeny Morozov’s 2011 book The Net Delusion provides a withering critique of the transformational possibilities of the Internet in general, but Facebook in particular. He suggests that the ease with which users can express sympathy with social causes through “like” and “share” buttons leads to what he calls slacktivism. Once one can identify with a social cause at a distance, there is little incentive to get directly involved in the serious and coordinated work of social change. Malcolm Gladwell made a similar argument in an October 2010 New Yorker article claiming that Facebook connections were based on “weak” ties rather than the “strong” social connections needed to sustain social change. Gladwell cited sociologist Doug McAdam’s 1986 finding that activists in the civil rights movement were personally affected by racism and discrimination and this personal attachment sustained the movement’s intensity. Since Facebook is based on a network model, whereas sustained social movements require some level of hierarchical organization, movements formed on Facebook will be too diffuse to produce lasting change.

In my own research, I come to a similar conclusion, but for different reasons. In my new book, Facebook Democracy, I examined 250 political Facebook groups. Few had been created for the purpose of mobilization, but this was not because of weak ties—in fact, rather than simply promote weak ties, Facebook seemed to amplify or dampen both the weak and strong tie bonds we form offline. Facebook can accommodate a whole range of different types of network formations. As James Fowler and Nickolas Christakis noted in their popular 2010 book Connected, individual networks can be small, long lasting, populated by like-minded people, and dense or they can be large, diffuse, and highly diverse. So it is that Facebook networks range from the college student who “friends” a stranger from halfway around the world or the husband who “updates” his wife to pick up a carton of milk from the supermarket. There is no one type of network formation that predominates on Facebook (and it is this diversity of network formations that makes Facebook so appealing for so many).

So why so little emphasis on mobilizing? Because Facebook emphasizes connection and disclosure over other forms of political discourse. And what happens when political discourse is about connection and disclosure? It effectively privatizes the public sphere. By taking the inherently intimate and personal act of disclosing to and connecting with others and putting it in what looks to Facebook users like a public forum, all sorts of conversations become personal, whether they should be or not. If the public sphere is about the objective social, economic, and political world we all share, what philosopher Hannah Arendt (1958) calls the “world of things,” the private/market sphere (like the one Facebook creates) is about the personal pursuit of self-interest.I find that the majority of political groups on Facebook are “informational,” intended to exercise political voice. For example, a site called “Ronald Reagan” was created specifically to show admiration for the former U.S. president. The creation of such a Facebook page is not intended to help users engage in a collective search for “the truth,” it’s an exercise in disclosing admiration and connecting with similar others. In effect, it is about “performing political identity.” This type of discourse is particularly prevalent on Facebook. One can hardly imagine someone bothering to stand on a street corner holding a sign that they support a president who hasn’t held office for over 20 years.

Media critic Lincoln Dahlberg noted that the great promise of the Internet was creating online rhetorical spaces that were free of elite control. This personalization of political discourse also necessarily focuses on those policy issues that are easy to translate into the personal language of feelings. It is much easier to process how one feels about Missouri Senate candidate Todd Akin’s “legitimate rape” assertions than it is to personalize the Greek debt crisis.

Personalization is not unique to Facebook: it exacerbates a long-term trend in Western democracies toward making the political world more intimate. Television has played a significant role in making candidate appearance and presentation of self matter as much as rhetorical content for candidate evaluations. But by personalizing and privatizing the public sphere, Facebook makes it harder to create “free” spaces, not because it is formally controlling discourse, but because discourse is driven toward subjects that are easily translatable into “feelings” that can be “performed” on Facebook.

This emphasis on disclosure is not restricted to homogeneous networks. Facebook is not, as Eli Pariser suggests, a “filter bubble” in which we can tune out dissonant voices. In his book, the current board president of activist group MoveOn.org, Pariser argues Facebook is one of a number of social applications that encourage users to live in a content bubble, where they are easily able to filter out information that doesn’t reinforce their preexisting beliefs. If that’s true, Facebook would exacerbate our already built-in tendency to group around ideological “tribes.” In reality, Facebook users have more diverse networks that we might presume: Facebook isn’t a political blog like Daily Kos or Red State. Facebook connections are primarily formed around social/geographic proximity, not shared interests like on other parts of the web. As such, Facebook is less likely to promote individual filter bubbles than other sites.

Granted, social proximity and shared interest overlap to some degree: people in the same upper-income neighborhood are likely to share similar interests. However, this overlap is less pronounced when it comes to political attitudes. Sharad Goel and his colleagues at Yahoo found that Facebook friends were more homophilous in their political views than random groups, but the difference (75% agreement for Facebook friends vs. 63% for randomly assigned groups) was marginal, albeit statistically significant. Perhaps more curious than whether individuals are exposed to diverse views on Facebook is the fact that Facebook appears to be a generally apolitical forum. As Goel and his colleague noted, Facebook users:

are probably surrounded by a greater diversity of opinions than is sometimes claimed, (but they) generally fail to talk about politics, and that when they do, they simply do not learn much from their conversations about each other’s views… the extent to which peers influence each other’s political attitudes may be less than is sometimes claimed.

This is the main problem with “talk” on Facebook. Because of its structure, the social networking site encourages the performance of political identity over deliberation. But discourse like this doesn’t reflect or encourage a collective search for the truth or a particularly effective preparation for democratic citizenship. Identity formation is only a stage in the political process, so Facebook, as a business, has no interest in the transition of a public political identity into a public citizen engaged in political life. In fact, having a political identity or a political opinion is not politics. Politics is about engaging in a collective conversation about how we should pursue the good life. That collective conversation does not mean some fantasy town hall where every citizen is completely open-minded and engaged with the issues. But it does mean actively engaging in the political arena and recognizing that public life in a democratic society is about accepting a set of ground rules for the greater public good.

In another argument for Facebook as the great democratizer, Facebook makes your representative more available to you. At first blush, it seems to present constituents with unprecedented opportunities to access political information and to do constituency service. But Facebook as a medium demands that politicians seem “authentic” and compels them to “disclose” and “connect.” The very notion of “following” or “liking” one’s senator connotes a personalization of the constituent/representative relationship, though, so this personalization of politics, this demand for authenticity, means politicians need to appeal to emotion, not policy. Politicians move away from a collective search for the truth (or, at least, a productive political conversation), and toward easy appeals and emotional responses to policy issues.

Sometimes such personalization is essential. Facebook’s effect in galvanizing the 2011 Egyptian revolution, for example, is undeniable. A Facebook page called We Are All Khalid Said, created to memorialize an Egyptian citizen killed by police, served as a site for everyday Egyptians to express collective dissent. Here, and in other places, Facebook can provide a vehicle for the personal expression of political views, especially where individuals’ rights are constrained. It is particularly in places that don’t have respect for the individual that individual “voice” matters. However, an overemphasis on the personal in rights-based societies filters politics through feelings rather than emphasizing politics through the lens of a collective search for pragmatic truth.

In democratic states in which voice is guaranteed by law, listening, rather than expressing, becomes an equally important quality. Early utopian thinking about the Web posited it as a radical public sphere (Salter 2005) where alternative voices could be heard. But unlike blogs with discrete URLs, Facebook does not provide independent pieces of Internet real estate. Instead, Facebook corrals all these voices in one place. Even in Egypt, listening was necessary to foment revolution. Barry Wellman and his colleagues highlight how the seeds of the revolution were sown by Egyptian bloggers who fostered a “networked public sphere” of social critics. Without this community of voices providing spaces for political deliberation, the Khalid Said Facebook page would have had little effect.

In the U.S., balancing more voices with more listening remains crucial for democracy to flourish. If Facebook’s main purpose is to enhance social connection, then controversial (e.g., political) subjects run the risk of inhibiting the formation of these bonds. This is where I think Facebook has the largest impact upon politics. Facebook encourages a further privatization and personalization of the civic sphere—a place that is inherently public, and in which everyone should both express personal identity and come together to deliberate over the good life.

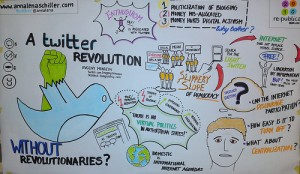

What does all this mean for the upcoming elections? It means that, on Facebook at least, we are likely to talk about how we “feel” about pressing political issues and politicians, rather than the issues themselves. Political figures exacerbate this trend by personalizing themselves on sites like Facebook. Knowing whether President Obama likes Stevie Wonder should be less relevant than whether his proposal for remedying income inequality is likely to be effective, but Facebook exacerbates a trend toward political personalization of politics. Still, it offers a great many elements that make it advantageous for politics. In the 2010 book Digital Activism Decoded, Mary Joyce and her contributors found that many grassroots organizations rely on Facebook to promote their cause and coordinate activities. While Facebook’s disappointing initial public offering may have dampened some of the enthusiasm over Facebook’s transformative possibilities, this one giant site is not the end of the social media story. New social media tools like Twitter, Pinterest, and Google+ are on the rise. These might provide alternative models of communication that enhance public discourse in ways that Facebook cannot.Recommended Reading

Matthew Hindman. 2007. The Myth of Digital Democracy. An empirical analysis that challenges the notion that the Internet enhances the diversity of political discourse.

Rebecca MacKinnon. 2012. Consent of the Networked: The Worldwide Struggle for Internet Freedom. Clearly highlights the subtle way authoritarian systems use the Internet to maintain power.

Evgeny Morozov. 2011. The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom. An important critique of the impact of Facebook and the Internet on promoting liberty and fostering social movement mobilization.

Zizi Paparachizzi. 2010. A Networked Self: Identity, Community and Culture on Social Network Sites. An excellent analysis of how the Internet changes the nature of social relations and our individual self-presentations.

Eli Pariser. 2011. The Filter Bubble. What the Internet is Hiding from You. A useful practitioner analysis of how Facebook and the Internet personalize everyday life for users.

Comments 3

Meghna — October 28, 2012

I agree with a lot of statements made in this article about the advantages and disadvantages of Facebook during the elections or in more general politics. One statement was made that those most likely to use Facebook are least likely to be engaged with politics. I disagree with this. Teenagers who have a Facebook are more likely to want to be more engaged in the political process if they see topics they are interested in and want to get in engaged in. While this might get the people wanting to be more engaged, I agree that “likes” on Facebook pages do not translate into votes or actually getting out and engaging in political activities. This is the point on slacktivism that the article talked about. This happens even at college. Many students “like” the organization they want to get involved in on but never actually go to meetings are really get involved. Also, even though Obama has so many more likes on Facebook, the election is still closer than ever. In addition, Facebook is used for various things. Those who use it for entertainment will not get as much political information as those who seek out political statuses and want to be more informed in that area. While Facebook is one revenue for political updates, the New York Times or CNN or much more qualified sources to look to if people really want to be politically informed. Facebook updates are limited based on your friends. If you only friend liberals, the updates will be heavily skewed. Facebook seems to be a good start to start getting politically informed.

Alessandra Ilieff- Essay in Lieu of Exam: Politics, the Public and Publishing. « a.ilieff — November 6, 2014

[…] http://thesocietypages.org/papers/facebook/ […]

Facebook and Politics? – laurelhedtke — October 1, 2016

[…] arguably lessening political participation as a whole. According to Jose Marichal in his article “Facebook’s Impact on American Politics”, those most likely to use Facebook are also least likely to be engaged with […]