Editors’ Note: The author prefers to capitalize Black and White along with other socially constructed racial categories.

For much of American history, race has been a dichotomous, Black-White affair where the “one-drop rule” dictated that people with any amount of racial mixture were defined legally and socially as Black. In recent generations, however, with the rise of intermarriage and the entrance of new immigrants from all over the world, American racial categories and conceptions have become much more complicated and contested. Latinos provide a particularly revealing case of the new complexities of race in America.

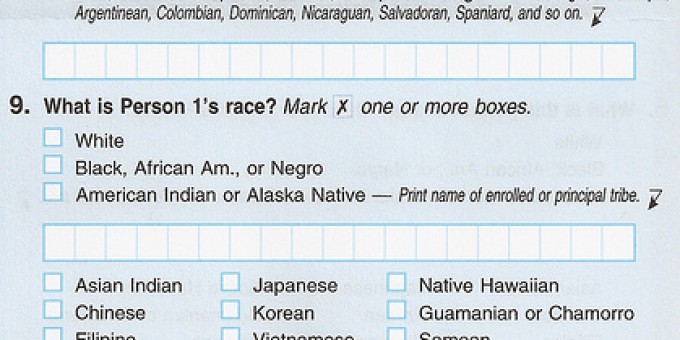

Persons of Hispanic ancestry have long had mixed racial identities and classifications. The history of Latin America is characterized by the mixing of European colonizers, native Indigenous groups, and Africans brought over as slaves. As a result, the diverse Latino group includes people who look White, Black, and many mixtures in between. In the mid-twentieth century, it was assumed that as they Americanized, Latinos who looked European would join the White race, while those with visible African ancestry would join the Black race, and others might be seen as Native American. For 50 years, the Census has supported this vision by informing us that Latinos could be classified as White, Black, or “other,” but not as a race themselves. “Hispanic” remained an ethnic, not a racial, category.

But today, few think twice when a breakdown of races in America includes, among others, the categories Black, White, and Latino. Throughout our media and popular culture—in newspapers, television, social media, and even academic research—we tend to treat Whites, Blacks, and Latinos as if they were mutually exclusive groups. How has this come about, given that the United States has long insisted that “Hispanic” or “Latino” is not a race, but an aspect of ethnicity?

But today, few think twice when a breakdown of races in America includes, among others, the categories Black, White, and Latino. Throughout our media and popular culture—in newspapers, television, social media, and even academic research—we tend to treat Whites, Blacks, and Latinos as if they were mutually exclusive groups. How has this come about, given that the United States has long insisted that “Hispanic” or “Latino” is not a race, but an aspect of ethnicity?

To answer this question, I studied Dominicans and Puerto Ricans, two groups whose members span the traditional Black/White color line. I interviewed 60 Dominican and Puerto Rican migrants in New York City, and another 60 Dominicans and Puerto Ricans who have never migrated out of their countries of origin. We spoke about how they understand and classify their own and other people’s races, their perception of races in the mainland United States and their home country, what race means to them, and the migrants’ integration experiences. Their interviews revealed that most identify with a new, unified racial category that challenges not only the traditional Black-White dichotomy but also the relationship between race and ethnicity in American society. In other words, the experiences of these groups help us to better understand how immigrants’ views of collective identity and the relationship between color and culture are reshaping contemporary American racial classifications.

How Dominicans and Puerto Ricans Understand Identity and Race

My respondents all identified primarily as “Latino,” “Dominican,” or “Puerto Rican.” Even among those who had migrated to New York City, these were strongly held identities, associated with language, culture, and nationhood—the kinds of attitudes, attributes, and claims American scholars tend to associate with ethnicity. But many respondents also gave the same answers when asked specifically how they identified their race. They explained that, with their country’s history of racial intermixing over many generations, the meaning of “Puerto Rican” or “Dominican” is itself racialized as the mixture of White, Indigenous, and Black. For instance, Blanca, an arts administrator in Puerto Rico, looks European. Because of her mixed roots, she identifies herself as Puerto Rican.

Many Puerto Ricans consider themselves… [a] mixture of blancos, indios and negros…. I consider myself a mixture of blanca, negra and maybe india…. I don’t consider myself mulata because mulato is blanco and negro. I consider myself Puerto Rican, and the Puerto Rican is that.

Q: Puerto Rican is blanco, negro, and indio?

Yes. I don’t know if I have indio race and I don’t know if I have negro race but if I look at myself in the mirror I think that, although I have, look, straight hair and I’m more blanca than negra, but I’m a Puerto Rican. There is no way that I’m not Latina.

Gregorio, a taxi driver from the Dominican Republic, identifies his race as Dominican.

Regardless of whether African, Indigenous, or European features predominate, Dominicans and Puerto Ricans view “race” as this shared ancestry, not as something that divides them. Puerto Ricans and Dominicans refer to a range of physical appearances as “color,” but insist that such appearances—such as blanco, negro, mestizo, trigueño, and a host of others—are not their race. Eduardo, a young Dominican administrative assistant in Santo Domingo, gave a response typical of both groups when he said, “They’ve taught us that this is color… for me, they’re only skin colors.” Many respondents believe that “color,” or appearance, is just a matter of chance—what happens to get expressed—but that a person’s racial mixture is latent and can present itself in future generations.Q: Could you tell me what race you consider yourself to be?

Well, from the country, I mean, Dominican. Dominican.

Q: Okay. And would you say that Dominican is a race?

Yes, I believe so. Yes, because… each country has its race of origin…. I’m Dominican and everywhere you go, you say, “What country [are you] from?” or “What race?” Well, you say, “Dominican.”

For instance, Jaime, a Puerto Rican professor in San Juan, locates the essence of the Puerto Rican race in an ancestral inheritance: “If… you’re Puerto Rican, [and] you have the races, Spanish, Indian, and African, then that’s your race. And it doesn’t matter if you’re more blanco, or if this one is more negro, and they got married, the son still has the race. You see? Because the race isn’t lost, the pedigree isn’t lost, you know, you carry it.” As a result, Jaime maintains, “I don’t think that the color defines a race.” This view of “Puerto Rican,” “Dominican,” or even “Latino” as a mixed racial ancestry is quite different from how Americans traditionally think of race and distinguish it from ethnicity.

Confronting the American Racial Context

Studies by scholars such as Laura Gomez and Julie Dowling show that other Latino immigrants, such as Mexicans, have similarly understood their ethnicities as a mixture of races. I found that when my migrant respondents first came to the mainland U.S., they brought this “mixed” understanding of race with them. When early migrants arrived, this view ran up against the prevailing American racial images and categories, especially those associated with darker skin tones.

Most people from the Hispanic Caribbean have some African ancestry, which would have led to them being classified as Black under the United States’ one-drop rule. This surprised and often frustrated migrants who identified their race in terms of their nationality. Celia, a Puerto Rican school counselor who was sent to live with her older sister in New York in 1955, explains:

I discovered so much about racism when I came to this country… When I came to school… for my ethnicity, they put Black. And then my sister went [to correct it] and she said, “She is a Lat—” At that time we didn’t use the word “Latino.” We said Puerto Rican.

Q: …Did they change your race on the form?

Yeah, they changed it… I don’t think they gave her a hard time. But yet, it was a problem. It was a problem.

The problem, for Celia, was one of respect. Being classified as Black not only imposed a race she did not accept, but also implied a lower status.

Because of their treatment as Black, even where Puerto Ricans and Dominicans have been allowed to live and travel has been constrained. Antonio, a Puerto Rican migrant who arrived in New York in 1947, settled in Spanish Harlem. He became aware of racial divisions through the territorial demarcations that divided his neighborhood landscape:

East Harlem was divided into two portions: the portion east of 3rd Avenue and the portion west of 3rd Avenue. East of 3rd Avenue was where all the Italians lived, and there was a tremendous amount of fights between the kids. And the demilitarized zone was 3rd Avenue because it had an “el,” an elevated train. I had to go to the elevated train to go downtown or whatever so that was a place that it was safe to go. But you wouldn’t go past [east of] that and the Italians couldn’t go west of that. I was very young when I first became aware of that because we were told “Don’t go east of 3rd Avenue or your life is in danger.” …And then west of that was Central Harlem where all the Blacks were living and we mixed with Blacks.

The African Americans Antonio grew up with could not understand why he did not identify as Black. Having internalized the one-drop rule themselves, they insisted, “If you’re mixed, you’re Black.” This, after all, was their reality.

But much has changed in recent years, led in no small part by the tremendous growth of Latino populations. In New York City, the Puerto Rican population grew from about 600,000 in 1960 to almost 900,000 in 1990. Between 1960 and 2000, the Dominican population grew by more than 3,000% to become the second-largest Latino group in the city. Moreover, the entire Latino population of New York City has surged from less than 10% in 1960 to 27% in 2000 and has become increasingly diverse. With more than one in four New Yorkers identifying as Latino, native-born Americans are more familiar with these populations, and the communities themselves have more power to determine how they will be classified.Celia, quoted above, now teaches at a school in the center of Spanish Harlem. In her school, Latinos are the majority, and there is no question that staff and administrators are fully sensitive to their cultural backgrounds and unique way of thinking about race, nationalism, and ethnicity. The size and prominence of the population has helped them assert their view of race as based on culture, a view that also fosters a shared Latino identity. And just as “Puerto Rican” or “Dominican” represented the particular mixture of Spanish, African, and Taíno peoples, these migrants have applied their understanding of race to view “Latinos” as a mixed-race group. This is much like José Vasconcelos’s notion of a “cosmic race” created out of the blending of peoples in Latin America. In racializing the “Latino” category, many respondents highlight the contrast to European Americans, who historically tried to avoid the racial mixture that characterizes modern Latinos.

Migrant respondents tend to emphasize their Latino identities in situations where they see it as advantageous. Those with darker appearances find it particularly useful to distinguish themselves from Blacks. Yesenia, a retired Puerto Rican garment worker, explained, “Negro [dark-skinned] Puerto Ricans don’t want to be Black Americans…. When they come in the elevator and you think they are Black Americans and you speak English to them… they quickly speak Spanish to you.” Speaking Spanish or revealing their name is usually enough for others to “reclassify” those initially “mistaken” for Black.

But Not White, Either

But by the same token, those with lighter appearances often find that Americans do not accept them as White. When they assert a White identity, an identity many held in their countries of origin, light-skinned Latinos are often corrected by people around them. Carla, a Dominican lawyer, learned that she is no longer considered White through an experience at college.In my country, I’m very light in color. That is, very, very light among Dominicans. I even think that my personal identification card… said White. And actually I considered myself White before, until I came here. And later when I arrived here I realized that no, that I’m not White and that actually I realized what discrimination was, that is, being treated differently.

Q: And how did you realize that you… aren’t White?

That happened one day when we were at the university, my friend and me. My friend is also Dominican and she is negra. We were studying at the university until very, very late [so we were told to call] the security office and ask them to accompany us to our home… So I called, and they asked me how we looked… I told them that we were two women and that one was Black and the other one White. And my friend who had lived in the U.S. for some time laughed and she told me, “Do you think that you’re White?”

Through reminders like these, light-skinned migrants learn that the most privileged racial category is the hardest to join. Either through their own efforts to move up the racial hierarchy or other people’s efforts to keep them down, Latinos of all appearances find themselves occupying a middle rung on the country’s racial ladder.

Of course, light-skinned Latinos could become White by integrating culturally—losing their accent, language, and their Latino identity. But many of the migrants I spoke with did not. In addition to being proud of their roots, they also saw distinct advantages to being bilingual and bicultural in a country with a growing Latino community. Nilda has light skin and could pass for a White American, but when applying for jobs she finds that it helps to be seen as a Puerto Rican English speaker. Even if her English is not perfect, her ability to speak Spanish lifts her above other job candidates, especially in customer service.

Migrants of all appearances recognize the tremendous potential of being able to “navigate in two worlds” as the Latino community (and market) grows, which makes them reluctant to fully “Americanize.” Even for those who are largely acculturated, the prominence of the Latino community in New York City’s psyche keeps the identity alive. Subtle indications of their origins—their name, references to their family roots—remind others that they are part of this group. Unlike an ethnicity, the Latino race does not seem to be fading over time.

Immigration, Integration, and Race and Ethnicity

In August 2012, the Census Bureau announced that it is considering replacing the separate race and Hispanic origin questions with one combined question that will place “Latino” on equal footing with other recognized race categories. In recent censuses, about 40% of Latinos have chosen not to select White, Black, or one of the other races listed and have instead marked themselves as “Other” race. Many interpret this to mean that they identify their race as Latino or as their nationality.

But will being seen and now counted as a race affect Latinos’ place in the American social hierarchy and their opportunities for empowerment? In her book In the Shadow of Race, Victoria Hattam suggests that U.S. groups that have been viewed as ethnicities have experienced more social mobility over time while those viewed as races are often relegated to the bottom of society. In effect, she suggests that there are some real costs to being seen in racial terms.

However, most of the groups that were defined as ethnicities and experienced mobility in the past were European, a category that was already, in effect, racialized and associated with Whiteness. They tended to lose their primary attachment to their ethnicity as they acculturated and were able to position themselves as part of the White race. This has always been far harder for those with African ancestry, who are unlikely to be seen as White no matter how integrated they are.

It has also been difficult for groups to shed a strong ethnic identity when they experience ongoing immigration, as sociologist Tomás Jiménez has shown. A steady stream of newcomers ties the group to its immigrant origins in the public mind. In this sense, Latin Americans are different from earlier European immigrants. The Depression and World War II spurred decades with little immigration when European groups could shed their immigrant identities. But steady Latin American immigration over the last 50 years has produced an association between our images of “Latino” and “newcomer.” Latinos are in a unique position relative to other immigrant groups, past and present. Some members of the group—those with light skin and Americanized behavior—could have followed the path of earlier groups toward Whiteness even if it meant changing their names or hiding their origins. But other members—actual newcomers and those with darker skin—influenced public perceptions of the group overall.The fact that Latinos have not, by and large, shed their Latino identities also creates advantages for the group as a whole. Groups that identify their shared interests and structural barriers are more likely to be involved in political mobilization. Yen Le Espiritu has shown this to be the case among Asian Americans who have fostered a sense of Asian pan ethnicity with common structural positions and shared interests that stem from their racialized treatment. A Latino identity functions in a similar way. The attention given to Latinos in the 2012 election cycle shows their ability to mobilize as a voting bloc, and Latinos will likely only continue to use their numbers for political gain.

The intertwining of race and ethnicity in the national imagination has created greater solidarity within the group. That can improve the situation of all Latinos rather than the lucky few. A common racial identity allows those with lighter skin and greater advantages to share resources and information with those with darker skin. In other words, the Latino race, whether embraced or imposed, might help to lift the entire group and not just those members who are able to jump across the color line into Whiteness. As they form a strong political voting bloc and gain the ability to self-identify on official documents like Census forms, American Latinos will continue to further express their identity and challenge the ways Americans have traditionally thought about race and ethnicity.

Recommended Reading

Julie A. Dowling. Forthcoming 2014. On the Borders of Identity: Mexican Americans and the Question of Race. Austin: University of Texas Press. This study examines Mexican American responses to the census race question and explores the disjuncture between federal definitions and local constructions of race.

Yen Le Espiritu. 1992. Asian American Panethnicity: Bridging Institutions and Identities. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. A case study of how diverse national-origin groups can come together as a new panethnic group.

Laura E. Gómez 2007. Manifest Destinies: The Making of the Mexican American Race. New York: New York University Press. Uses New Mexico as a case study to explore the paradox of Mexican Americans’ legal designation as White but social position as non-White.

Victoria Hattam. 2007. In the Shadow of Race: Jews, Latinos, and Immigrant Politics in the United States. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. A comprehensive study revealing how the assignation of certain groups as ethnicities has reinforced the racial inequality of other groups.

Tomás R. Jiménez. 2010. Replenished Ethnicity: Mexican Americans, Immigration and Identity. Berkeley: University of California Press. A cleverly designed study that examines the role of continued immigration on later-generation Mexican-Americans’ identity and experiences.

Clara E. Rodríguez. 2000. Changing Race: Latinos, the Census, and the History of Ethnicity in the United States. New York: New York University Press. Uses historical analysis, personal interviews, and Census data to show that Latino identity is fluid, situation-dependent, and constantly changing.

David R. Roediger. 2005. Working toward Whiteness: How America’s Immigrants Became White: The Strange Journey from Ellis Island to the Suburbs. New York: Basic Books. Roediger shows how American ethnic groups—like Jewish-, Italian-, and Polish-Americans—came to be seen as White only after immigration laws became more restrictive in the 1920s and 1930s.

Comments 33

anonymous — March 21, 2013

I have to say I am extremely confused. Maybe it's because I'm young and grew up in a white-flight predominantly asian/hispanic/black community - hispanics have always been considered a race as far as I'm concerned, and I'm just as confused and surprised as those interviewees at what they faced. So just because the census is being changed to reflect reality, how would that affect their real social lives? They are already discriminated against.

If anything, giving them a racial category would help them - Asians are considered a race, even while everyone agrees that they have their separate ethnicities. In my humble opinion, what makes hispanics any more different from us asians, other than ancestry? Hispanic should not be considered an ethnicity - it is a race. Honduran, Chilean, Dominican are ethnicities, distinct ones at that. Having the public understand this would probably mitigate the belief that all hispanics are mexicans.

Azizi Powell — April 8, 2013

Thanks for an interesting read. I'm an African American with ancestry from the Caribbean and the USA.

As a general comment, I think that the realities of Puerto Ricans' and Dominicans' attitudes about skin color and economic conditions of persons with those skin colors both within Puerto Rico & the Dominican Republic and within the USA inform & influence what those persons from those countries consider their race & or ethnicity. In my opinion, this is one reason wny many of those individuals don't want to be categorized as Black.

But I differentiate between being Black and being African American, with "Black" being the larger category. That said, people who are Black [say from Africa, South America, the Caribbean, and -yes- also from Europe[ may elect to also be categorized as African American if they move to the USA.

Which brings up another point: Throughout your article you used "European" as the equivalent of "a member of the White race". I respectfully suggest to you that such a definition is "old school" given the increasing number of people living in-including born in-Europe who are not what White people would consider White.

Also, in an early statement in this article you wrote that “This view of “Puerto Rican,” “Dominican,” or even “Latino” as a mixed racial ancestry is quite different from how Americans traditionally think of race and distinguish it from ethnicity.". When you wrote that this is "different from how Americans traditionally think of race", I believe you actually meant "how White Americans" think of race...

African Americans have long known that we are a mixed race people.

One problem with race in the USA besides the HUGE problem of personal and institutional racism which got no mention whatsoever in this article, is that people are still using the "visual clues" test to determine race, notwithstanding the fact that there have always been people who are Black who don't "look Black" [that is, don't look like what mainstream White American think Black is "supposed to" look like". Ditto Native American, Asian etc. This "visual clues" test for race is butting heads with the contemporary stance about race in the USA that "you are who [what race] you say you are". And that stance is butting heads with the still prevailing notion of White exclusivity [You can't be White if you're not all White.]

One outcome of this belief in White exclusivity is the position that a person can't be or can't be accepted as belonging to more than one race when one of those races is White. I see some signs that this is changing and believe it will change even more given the increasing number of Latino people and the increasing number of mixed race people Latino or otherwise in the USA.

AllPeople (AP) Gifts [soaptalk AT hotmail DOT com] — April 10, 2013

Modern society really needs to begin to understand the simple fact that -- THERE IS NO SUCH THING AS A so-called 'LIGHT-SKINNED BLACK' person.

The truth of the matter is that such individuals are actually (and quite simply) people who are of a 'Multi-Generational Multiracially-Mixed' (MGM-Mixed) Lineage -- lineage that some of them may have been pressured and / or otherwise “encouraged" to ignore, downplay or even deny. http://dir.groups.yahoo.com/group/Generation-Mixed/message/4160

THESE (falsely) “black-categorized” INDIVIDUALS ARE, in actuality, the people who are actually of a continually MIXED-RACE lineage -- and the very term, itself, of “Light-Skin(ned) Black” is merely a racist-oxymoron that – (much like the racist-‘One-Drop Rule’ upon which this racist-term is actually based) – was created by racial-supremacists in an attempt to degrade Black blood lines.

THE ONLY WAY that a MIXED-RACE person COULD BE viewed upon as being racially-"BLACK" IS VIA an adherence to THE RACIST-‘ONE-DROP RULE’. THE RACIST-‘ONE-DROP RULE’ was a 100% non-scientific, socially-constructed "rule" that WAS CREATED by racial-supremacists in an insulting attempt TO DEGRADE all BLACK BLOOD LINEAGE – AND – which WAS also LEGALLY-BANNED in the U.S. back IN 1967. http://dir.groups.yahoo.com/group/Generation-Mixed/message/4162

The FACT that the racist-’One-Drop Rule’ was created to DEGRADE Black blood lineage means that any BLACK person who supports the (clearly ‘Black-Lineage Degrading') racist-'One-Drop Rule' either has no self-esteem, is insane and / or is an idiot. (((The LINKS in the SIDEBAR of my YouTube

CHANNEL explain this in greater detail. https://www.youtube.com/user/apgifts )))

People of Mixed-Race lineage should NOT feel pressured to 'identify' according to any standards other than one's own. http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Generation-Mixed/message/4157

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Generation-Mixed/message/4162

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Generation-Mixed/message/4160

Listed below are related Links of 'the facts' of the histories

of various Mixed-Race populations found within the U.S.:

There is no proof that a 'color-based slave hierarchy' (or that 'color-based social-networks') ever existed as common entities -- within the continental U.S.

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Generation-Mixed/message/4154

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Generation-Mixed/message/4153 .

It was the 'Rule of Matriliny (ROM) -- [a.k.a. 'The Rule of Partus' (ROP)] -- and NOT the racist-'One-Drop Rule' (ODR) -- that was used to 'create more enslaved people' on the continental U.S. This is because the chattel-slavery system that was once found on the antebellum-era, continental U.S. was NOT "color-based" (i.e. "racial") -- but rather -- it was actually "mother-based" (i.e. 'matrilineal'). http://www.facebook.com/allpeople.gifts/posts/309460495741441

There were many ways (and not solely the sexual assault and sexual exploitation of the women-of-color) in which 'white' lineage entered the familial bloodlines of enslaved-people found on the continental U.S. http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Generation-Mixed/message/4238

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Generation-Mixed/message/4239

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Generation-Mixed/message/4240

An 'Ethnic' category is NOT the same thing as a "Race" category:

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Generation-Mixed/message/4236

http://www.facebook.com/allpeople.gifts/posts/300777016632181

Letta Page — April 26, 2013

For those planning to use this article in the classroom, check out Kia Heise's great Teaching TSP discussion guide! http://thesocietypages.org/teaching/2013/04/02/latino-race-or-ethnicity/

Domingo Hernandez — September 25, 2013

DNA studies are showing in Puerto Rico that the averge Puerto Rican is tri-racial with the European contribution being the largest around 63% the African and Amerindian following almost neck and neck. This however does not take away the fact that thousands are White without mixture and there are also thousands who are Black without mixture. Not everyone in PR. agrees with the cosmic race. Why is it so difficult to understand that these islands are multiracial and even multicultural? What race are North Americans? Why are we not asking that question? It's the same answer for us. The only difference is that we have a larger percentage of tri-racials where as in the USA these are of a smaller percentage.

Lara C Andrie — October 15, 2013

I totally agree with Domingo's comment.

I'm brazilian and there are not a more mixed country then Brazil.

We have the second Japanese population outside Japan, we have the second black population just smaller then Nigeria, we have a Lebanese population even bigger then Lebanon population.

We have the second big Oktoberfest outside Germany , third Italian population, US is the second, I can go on and on. What a lot people doesn't know too is ,we do not have a lot of Native in Brazil. The Portuguese (yes, we speak portuguese)killed a lot of them, we have some tribe in Amazon.

Brazil is a mixed country, but not everybody are mixed. Brazil has a very close history to US history.

Brazilian do call them Latin, but the only reason is because we speak a Latin language , that's it.

We do not understand this latino conception that was created here, I don't know if it was created by US or

by Hispanic population,. I see a lot of people proudly calling themselves latino, to tell you the truth they look Native to me, that's what I think latino are.

History teach us that there are just 4 race group category.

Caucasian (white) Mongolian (yellow, Asian),Ethiopian (black)and Native American, the other are invention, even though I think it's ridiculous to divide people into categories , I still think that human is a better way to describe us, because that what we really are, some with a very peel skin, some a little dark, some a little yellowish, some very dark. The place you leave have a lot to do with the color of your skin too. Why can't people understand that beside the skin color we are all the same.

Sorry for my bad English , I still learning.

Emadia — November 19, 2013

Lara C Andrie

Uganda is more mixed than Brazil.

Brazil is an ethnically diverse country, but it is less ethnically diverse than most African countries. Your neighbour to the north, Suriname, is probably also more diverse: it's said to be the most ethnically diverse country in your region.

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2326136/Worlds-apart-Uganda-tops-list-ethnically-diverse-countries-Earth-South-Korea-comes-bottom.html

Friday Roundup: Awards Edition! » The Editors' Desk — December 20, 2013

[…] “Creating a “Latino” Race,” by Wendy Roth. […]

AD Powell — January 19, 2014

Wendy Roth is wrong. There was no universal "one drop rule." Various amounts of "Negro blood" were allowed in the "white race." "Acting whiteness" or exercising the privileges of whiteness was often more important than percentages of "blood" is cementing white racial identity.

rrobin22 — February 20, 2014

I thought this article was interesting being that I am mixed (black, native, and german ) and being born here in the states I refer to my race as American much like the Puerto Ricans do. End of the day, I think race is an illusion used to separate us .

Gino Savo — April 20, 2014

LATINO IT IS NOT RACE,IT IS A LANGUAGE THAT WAS SPOKEN BY THE ROMANS still in use at the Vatican,if you use an ATM at the Vatican it will be in latin not Italian, "latino" was an invention and pretext from the French to conquer Mexico in the 1860'S before that it was known as America Hispana

Gino Savo — April 20, 2014

besides LATINO it is an EUROPEAN yes an EUROPEAN terminology,does not make any sense to call a mixture of native American or African the term "LATINO" two different cultures,the THE REAL LATINOS are the spaniards, french, italians, in some degre romanians, portuguese and all of them are call latinos because of the language but not because of the race,besides they are many ethnical Groups in Guatemala and Mexico that they do not speak spanish and people call them latinos,thats ignorance

Al Rex — June 8, 2014

Latino means Latin. Latino/Latin is only a language, (Lingua Latina) the language spoken by the Romans, ancient Italians,who imposed their Latin Language upon the Spaniards when they colonized Spain called by them Hispania and remaining there for more than 700 years. Latino is neither a Race nor an Ethnicity and it doesn't have anything to do with speaking Spanish or being mestizo. Moreover, we don't identify people by the origin of their own languages. We identify people by their races: White,Black etc Hispanics will have to look into a mirror and figure out each one of them to which race or multiple races they want to be identify with. Latino doesn't have anything to do with their identification.

real latins dot org

T R Plume — June 18, 2014

The only "mixing" in this article is in the misuse of terminology. Phenotypical characteristics aside, you have included terms that are essentially undefinable. Pray tell, what is a Latino or a Hispanic? While both terms may have political and bureaucratic underpinnings they neither describe a "race" nor any particular societal heritage. The same goes for the nebulous term White. In effect, your essay reflects both a poor understanding of genetics and history. Let it suffice to say that the vast majority of all Americans are of mixed genetic lineages. This fixation on color and self identification reveals nothing more than the continued ignorance most people have about evolutionary and migrational patterns. Paradoxically, the most "pure blooded" people in North America tend to be of Native American descent who are neither mestizo or "Hispanic/Latino" or any of the other racially motivated term now in vogue. They are, in fact, Native Americans who can trace their sojourn in North America to the Pleistocene.

vincent vanasco — July 27, 2014

My goodness. Such a fuss.No one is a pure anything. We are all mixed from somewhere down the line.It's the fault of fools who placed labels with no thought put into it.My friend an Attorney is a Spanish decent and abhors the word "Hispanic"I panic at "Hispanic" because it seems such a made up name.I too have a genealogy trace back to Spain in the 1100 hundreds,but migration turned up in Sicily. Get my drift.I am proud to be an American of Italian and some other ethnicity period.Spaniards called the island Hispaniola and the Romans called Spain Hispania. So tell me how they came up with "Hispanic"My Russian wife from Moscow who became a US citizen loves this country and does not get some of the labels people put on others. She is part Greek,possibly Polish as well as Romanian and some viking/slavic blood. Who does she look like?Almost everyone takes her for : are you ready? She is asked are you Italian,Spanish,Greek,Estonian,Sicilian,French,Irish and last but not least Russian!She is a beauty who encompasses all those looks.She travels a lot. So who are you?You are everyone and singularly YOU!

David Gonzalez — September 15, 2014

The saddest part of this article and the subsequent conversation, is that no one is pointing out the fact that we've all just accepted the fact that white is right in America. Whiteness is equated with privilege and affluence and we are almost encouraged to do away with our ethnic ties in order to sneak our way into Whiteness. It's sad.

Al Rex — March 1, 2015

Nobody is telling you to be White if you're not White. What we are saying is that Hispanics,that is people who descended linguistically and culturally from the Spaniards claiming origins in Latin America, stop identifying themselves as Latino/Latinos/Latinas and using these terms as their race or ethnicity. Latino is a language, the language spoken by the Romans who imposed their Latin language (Lingua Latina) upon the Spaniards in what they called Hispania in Latin. And Latin America doesn't mean Latino. Latin America is only a geographical location where people speak language derived from the Latin of Roman Italy and this is why the French called that area "Amerique Latine" because down there they spoke Latin languages: French,Portuguese and Spanish and were Christian Catholics with Roman Laws while here it was English-speaking, Anglo-Saxon and Protestants and they wanted to establish this clear difference. Hence : Latin America versus Anglo America. The fact is that now the Hispanics are twisting the meaning of not only Latino but also of Latin America. They have cut Latin America in a half and made it "Latino" and are using this term to identify themselves racially and ethnically and identify everything connected to them like Latin Food, Latin Women, Latina Women, Latin men, Latino men, Latin Dance etc, etc, when there is no such a thing. It's all an invention of the Spanish-speaking people of the Americas who don't like to be called Hispanics but need a name to unify themselves into one special group and have come up with this Latino invention exclusively for themselves. History cannot be changed. Everything Latin/Latino comes from Italy: The Latin people,the Latin Language and the Latin Culture all come from Italy and not from Spain and not from Latin America. The U.S.Census Bureau Should know this.

Odette — May 19, 2015

I don't understand why we keep categorizing ourselves as "White", "Black", "Asian", "Latin"... We aren't. it is very, very difficutl to find someone who is entirely just one race, because we simply don't do that. Ever since the discover of America and blah, blah, blah we started to mix. A race is supposed to be a group of people who share similar and distinct phisical chracteristics, not just the color of your skin or your hair.

I'm dominicain and that's it. Many people have tried to define me by india, trigeña, mestiza, and even "Kind of white and black mixed" and that was just by trying to describe my skin color. If they wanted to know my race, they'll have to spend half of their life searching. I mean, my grandma is dark-skinned whereas my grandpa is a (Very far) european descendent. The result? My light-skinned mom, my "Mestiza" aunt and my dark-skinned uncle. My mom doesn't identifies as white and neiter does my uncle identifies himself as black. They're just dominicain. My uncle has a white skinned daughter with dirty blonde hair. Is she black because of my uncle? No. Is she white because of her mom? No. She simply looks white, but she isn't.

Latino is not a race — September 12, 2015

Latino (Latin) is originally used to describe those who lived in the Roman Empire, and later inhabitants of Latin Europe. In the U.S., though, it's misused to describe people from Latin America regardless of race, assuming similar heritage. Needless to say, it's an utterly simplistic and delusional approach.

Despite the Anti-White propaganda, not everyone in Latin America is of Negroid descent or a mongrel. Many people in South Southern America actually are fully Whites, racially aware, who can easily trace their European ancestors. While not everyone is an Aryan (Nordic), they still are Caucasoids. Race has to do with your genetic make up, your phenotypic traits. Whites are Whites no matter where they geographically may be, and generally are racially well aware.

greg valdez — January 26, 2016

I know the top commenter's comment is old but he is very confused as to what race is because last time I checked Honduran, El salvadorean,Venezuelan,Costa rican and the rest of people of some latin American country are nationalities but ethnicities or race. There are people in those countries btw that don't speak Spanish but some indigenous dialect and there are some people that are descendants of Spaniards or other Europeans, most are of Spanish and native descent though and sometimes black African. There are also people that look entirely African in latin America.

greg valdez — January 26, 2016

are nationalities not ethnicities or races* The dude with the comment above me is correct not everyone in Latin America or from there is mixed in fact there are people who are unmixed native American or entirely European in those countries there are even people who look entirely black. What Dominican Odette said is right to some degree, but not every latino or person from the u.s , Canada, mexico ,central and south America or the carribean is mixed.

greg valdez — January 26, 2016

The commentar latino is not a race is kind of a racist but most of what he or she said is correct.

SobaSoba — February 6, 2016

Another correction. American is the demonym for people born on the American continent and it is extremely disrespectful not to acknowledge this fact. From Chile to Canada everybody born in any of the 35 Americans countries is an American.

The New World was named America by Martin Waldseemüller in 1507.

Latin America recognises race from a European consciousness | AfriKaNeedsToOwnItsResources — March 20, 2016

[…] Creating a “Latino” Race […]

Jesuisundoctor — March 24, 2016

The veracity is " Latino " isn't a race. I totally agree with most of the comments. Im somewhat perplexed by the these so call latinos who wrote comments about " 25 celebrities you didnt know were afro-latin american". Really! If were following the "one drop rule" hispanics are black period! Further, races have always been classified under four categories: there are as followed;black including hispanics, yellow, clearly asians, red, made up of indians ;and white. " Hispanics " see my quotation, haha are trying to create an identity to separate themselves so that they are not viewed as inferior. But all they are doing is encouraging the malicious demeanor of " racist ppl". I do not think their african grandparents or parent(s) would appreciate that.Hispanic are no less black than those kids are mixed and are classified as black. In my perspectives and based on supported studies from the "one drop rule" which I truly believe is absurd, then everyone of mixed race that have 1% black is black. Ok, those racist ppl were really dumm to have used such a word to make another human feel inferior;sad.

Jesuisundoctor — March 24, 2016

All Hispanics have African descents; no matter how light they may appear (skin-color), phenotypically, they can not hide who they are. These people keep trying to claim white. But when they turn their backs, whites people belittle them. I have witnessed a white girl who was married to a "Latino" said ," I do not know why , but my husband thinks he is white. the man is black because his grandparents are black,he's only degrading himself which bolsters that he is insecure about who he is, ridiculous! I love him as he is,black and hot ".

Tove — May 19, 2016

It of course makes absolute sense that different cultures view the concept of race differently. Specifically because race isn't a scientific concept, its a cultural concept like the difference between good music and bad music.

I can understand why most Americans would be confused by this, they simply lack worldly experience outside their own country, or own neighborhood lol. Race is a prominent social-belief in both North and South America, but since the mixing of different peoples throughout north america has been strictly taboo, i can understand why people in the USA can only understand skin color or physical phenotype. Its an honest mistake, but still a mistake, and a silly mistake and it speaks to the failure of North American societal education in this respect.

But i think if you can get out of your hyper-local experience, and understand just how america thought of race before latinos were allowed to live in the country, then you can see why its so confusing for both Americans and newly arrived Americans to grapple with how the USA views this issue.

Though i must say many latinos look like Native Americans but are treated differently because of their country of origin, and i can understand why most modern Americans don't think Latinos look like Amerindians, after all, there are so few left in North America.

Latino Rebels | Latinxs Are NOT Your Political Instruments — August 5, 2016

[…] of all generations living in the United States. The idea of Latinx as an ethnicity has been questioned in the past, and debate over what ethnicity itself entails continues to this day. But when Donald […]

Vero — October 17, 2017

If you want to use your not a race logic, then it will almost be face to say white nor black is a not race. They are colors not the color of skin. People are not the color of copy paper nor a sharpie marker. Caucasian is incorrectly used for europeans. And why is it alway the non latino trying to correct the Latino of which race to identify? In general latinos do not look at race the way other north American looks at it and has a different experience

AD Powell — August 17, 2020

Q: And how did you realize that you… aren’t White?

That happened one day when we were at the university, my friend and me. My friend is also Dominican and she is negra. We were studying at the university until very, very late [so we were told to call] the security office and ask them to accompany us to our home… So I called, and they asked me how we looked… I told them that we were two women and that one was Black and the other one White. And my friend who had lived in the U.S. for some time laughed and she told me, “Do you think that you’re White?”

______________________________

Sorry, but the "blanca" should not have believed the obviously jealous "negra." The white Dominican gave an accurate description enabling the police to easily find them. If the black one decided to interpret the word "white" as a boast of racial superiority instead of a physical description, that was HER problem.