What works

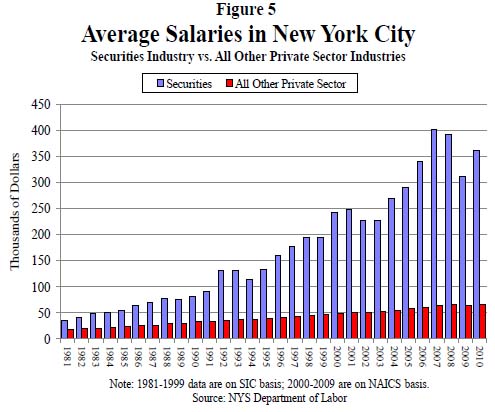

This may not be the worldest most attractive graphic, but it makes its point: financial workers have much, much higher annual income than the rest of us and the gap is growing over time. The text of the New York State Comptroller’s report said the same thing in words.

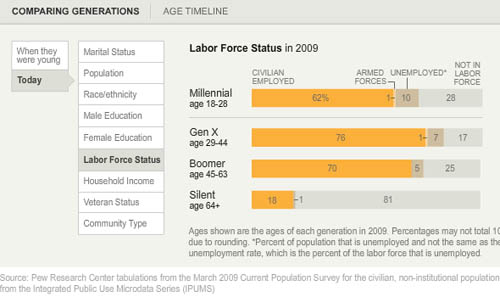

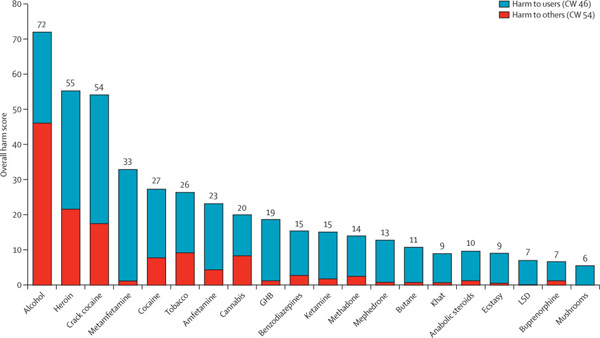

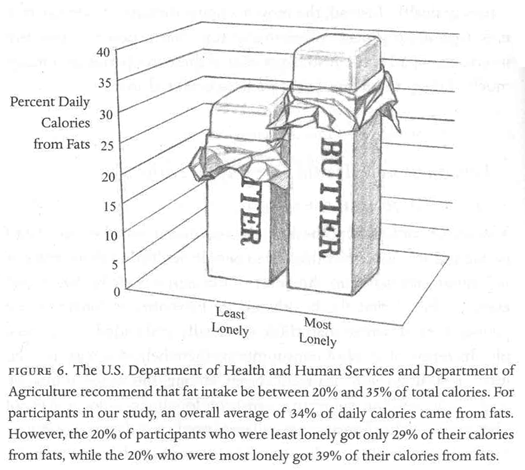

Wages (including bonuses) paid to securities industry employees who work in New York City grew by 13.7 percent in 2010, to $58.4 billion. Nonetheless, wages remained below the record paid in 2007 ($73.9 billion), reflecting job losses. In 2010, the securities industry accounted for 23.5 percent of all wages paid in the private sector even though it accounted for only 5.3 percent of all private sector jobs. In 2007, the industry accounted for 28.2 percent of private sector wages.

In 2010, the average salary in the securities industry in New York City grew by 16.1 percent to $361,330 (see Figure 5), which was 5.5 times higher than the average salary in the rest of the private sector ($66,120). In 1981, the average salary in the securities industry was only twice as high as in all other private sector jobs.

You be the judge. I think the graphic leaves a greater impact than the text alone. The two together are striking. Maybe we should…occupy Wall Street to demand a decrease in inequality?

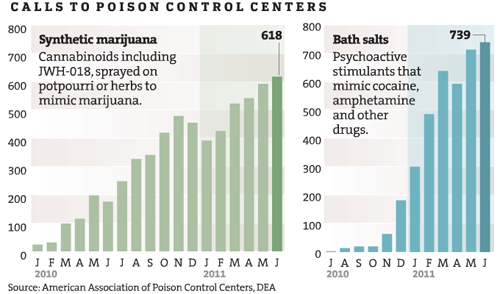

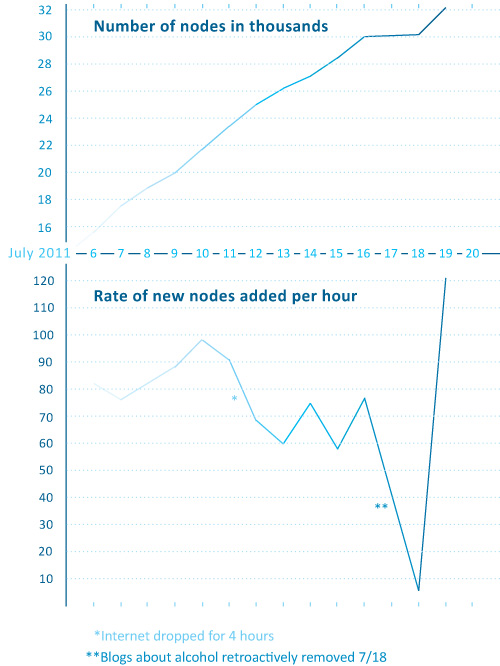

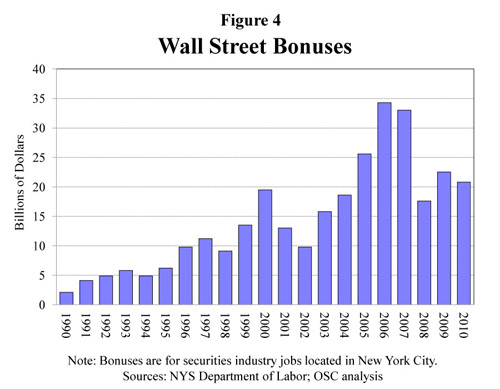

The short report has a few more interesting graphs. First, they throw together a quick graph of Wall Street bonuses. These bonuses are tied to performance and so big that they often represent more than a finance worker’s annual salary. As you can see, they took a dip, but they didn’t disappear even though the US economy is still not great.

The other interesting metric the report contains is a compensation-to-earnings ratio graph, which is the right context for this discussion. Bankers often defend their large salaries and even larger bonuses by pointing out how much money they have made for their banks. I agree with the bankers that this is the place to look. The question should not be: “How much are individual bankers making?” Rather, it should be, “How much does the banking sector make and is that the way we as a society want to distribute our surplus, primarily to banks and bankers through processes of financialization?”

What needs work

The graphs are not attractive and the first one reads as cluttered. I generally go with line graphs for this kind of trend data to cut down on the clutter impact, something I have repeated again and again so I won’t hammer on that point too much. I like the information behind these graphs so I am not going to swat at them too much. Excel is not a graphic design tool for graphs; I have occasionally made some sweet tables with it.

I’m glad the report put these data points into graphs, glad that the report is available during the discussions brought on by the OccupyWallStreet crowd, and glad that the New York State Comtroller’s office rolled right on ahead with the release of some fairly damning evidence against the status quo.

Want more?

Another Society Pages blog, Thick Culture, ran a post including graphs that deal with the compensation and wealth differentials between the tippy-top echelon of financiers and the rest of us at Tax Gordon Gekko.

References

DiNapoli, Thomas and Bleiwas, Kenneth. (October 2011) “The Securities Industry in New York City” Report No. 12, Office of the State Comptroller.

See also: A blog I wrote – Americans estimate our wealth distribution and fail. Horribly. using a Dan Ariely graphic about how bad Americans are at estimating the distribution of wealth in this country. Teaser: we think it is much more equitable than it actually is.

The most popular blog post of all time on Graphic Sociology: Champagne Glass Distribution of Wealth