The American Family – A demographic portrait

The New York Times has been running a variety of stories about American demography ever since the 2010 Census results were made publicly available. In this story (which came out last June…sorry for the delay), the article focused on today’s atypical families by spending time with a family comprised of a mom who used sperm donated by a gay friend of hers to have a baby. The biological dad stayed in the picture more than he had planned, as did his partner, though the end of the article hints that the biological mom and dad might be slowly coming closer to a shared living situation that more closely mirrors the traditional set-up.

That sort of one-off telling of the tale of a particular family is not what drew my attention. The larger demographic trends are what I find more fascinating and the interactive infographic offers a much less linear tool for exploring the changes in the demography of the American family than does the article. The article offers a narrative about a particular set of relationships. The infographic presents a question and then gives users enough historical and national context to poke around the possible answers to that question for themselves.

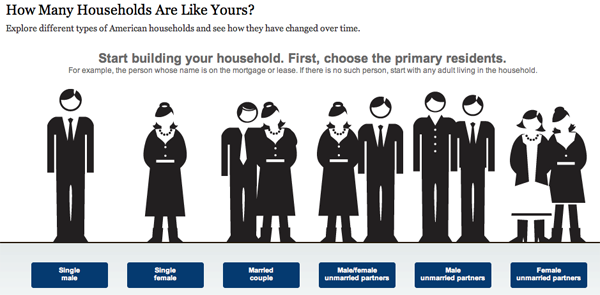

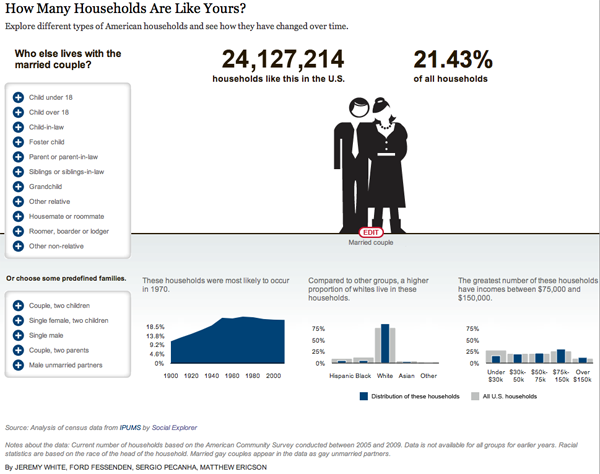

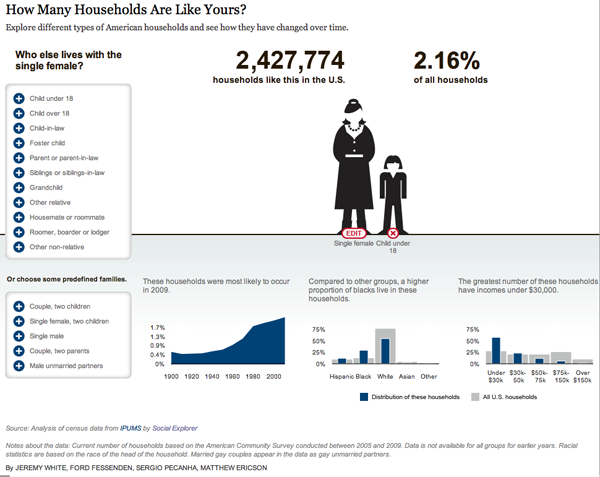

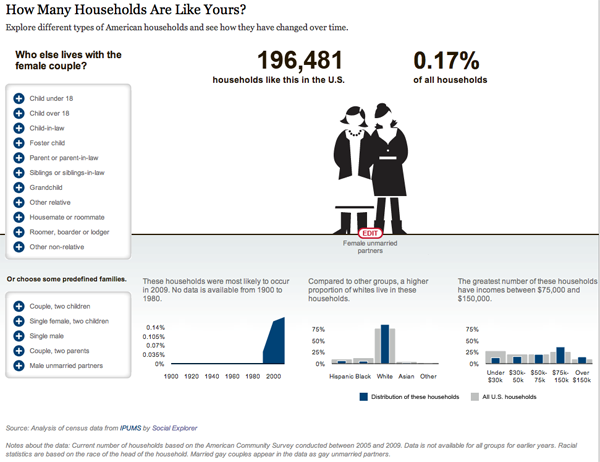

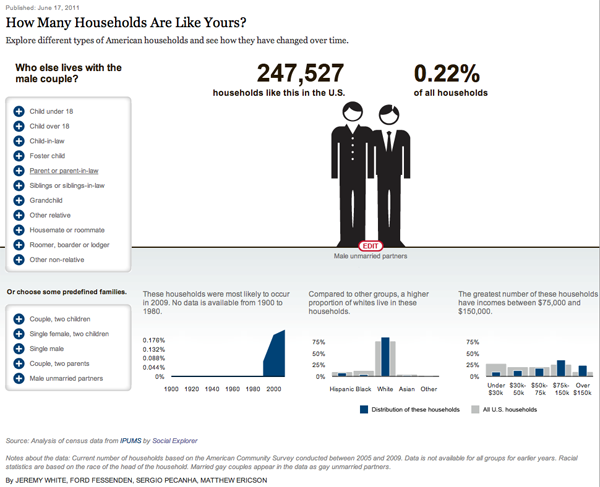

The site allows users to start with a head of household – that matches the way the Census is collected and makes sense. I picked a married couple above. Below I pick a variety of others but if you are sick of crappy screen grabs, feel free to go to the NYTimes site and choose the selections on your own.

What works

+ The graphic design is friendly without offending too many sensibilities (OK, the guy’s hair could be different to be more racially inclusive and it would be nice if the woman didn’t have to wear a skirt, but overall, I like the figures).

+ Another thing I like about the design is that they smack the percentage up there without feeling that they have to stick it in a pie chart or a graph or any other visual. They assume people have basic numeracy and can interpret a percentage without having to see it as a pac man…I mean pie chart. This leaves the visual field fairly clean and allows the focus to be on the family.

+ The graphs underneath the main family form do an excellent job of providing historical, racial, and income-based context. I love the history one – I think the big point about American family forms is that they are now and have always been subject to a fair amount of change despite the fact that it is fairly common to hear the “American family” referred to as if it were one kind of thing and had been since time immemorial.

+ The interactive component is excellent. Add some kids. Then kill them off. Or keep the kids and give them a different household head. Or get rid of the young kids and add adult kids. Or forget kids and spouses: just add siblings. Besides how much fun I had doing this, I ended up exploring many more angles of the American family demography question than I otherwise would have.

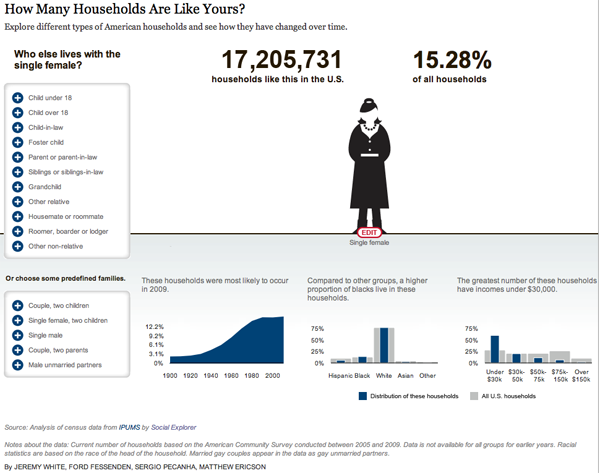

Of course, I was interested in what the story is for people like me (single women)…

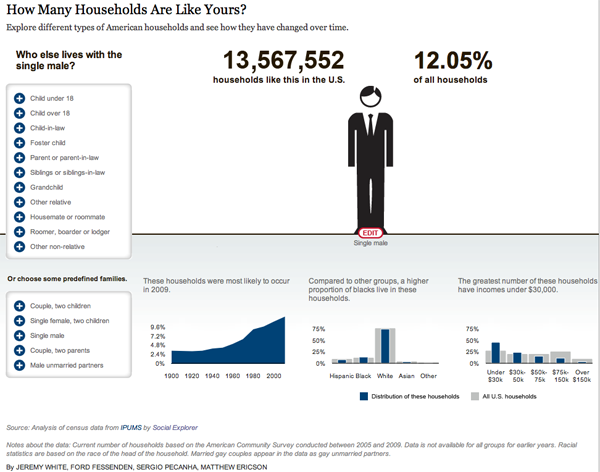

if I were a man

…and whether or not my situation would be different if I were a man. I was surprised that there are more single women than men until I remembered that men die younger so I bet that the difference shows up at the later end of the life course, not so much among my age cohort.

on the other hand

…or had a child on my own like the woman in the article.

What about the same sex couples? Not exactly a huge percentage of the population, but the Census data upon which this was based are having trouble keeping tabs on the variations of legal statuses of same sex cohabiting couples. In some states same sex couples could marry in 2010, in some states not so much. This is a trend to watch in 2020 and 2030.

What needs work

I wish there were a way to visualize ‘any children’ instead of having everything broken down by age and number of children. I found myself curious to figure out how many households had kids, who they were, and whether or not they were single-headed, couple-headed, same-sex couple-headed and so on. But there’s no way to do the basic kids vs. no-kids comparison here.

Accessing good data online

This contemporary overview of American family demography was put together by some of the digital team at the New York Times and ran alongside “Baby Makes Four, and Complications”. It uses IPUMS data (which came from the US Census but had to be cleaned up and made properly malleable for crunching with statistical software before it could be analyzed).

The Integrated Public Use Microdata Series – IPUMS – is a project based at the Minnesota Population Center and used widely by American social scientists to study both domestic and international demography. Users – and just about anyone can become a user – can download subsets of the US Census suitable for data analysis on typical desktop computers. The subsets are random samples of the full Census and are generally considered to uphold the highest standards currently outlined for use with the statistical modeling techniques that common among social scientists. While IPUMS is an excellent, fantastic, extremely valuable resource for academic researchers. The Social Explorer, a website supported by Oxford University Press and headed up by Andrew Beveridge at Queens College and the CUNY Grad Center, tries harder to produce public-facing reports using data from IPUMS as well as the American Community Survey and other large-scale surveys. The Social Explorer also makes data available for others to analyze, so between IPUMS and The Social Explorer, it is much easier to get good data sets for analysis than it was in the past.

References

Kleinfield, N.R. (19 June 2011) Baby Makes Four, and Complications New York Times, NY/Region Section.

Steven Ruggles, J. Trent Alexander, Katie Genadek, Ronald Goeken, Matthew B. Schroeder, and Matthew Sobek. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 5.0 [Machine-readable database]. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2010.IPUMS USA website

Beveridge, Andrew, et al. The Social Explorer website. New York: Oxford University Press.

![Visualizing How A Population Grows To 7 Billion | NPR [Click for video]](https://thesocietypages.org/graphicsociology/files/2011/10/NPR-world-population-growth-still-01.jpg)

![Visualizing How A Population Grows To 7 Billion | NPR [Click for video]](https://thesocietypages.org/graphicsociology/files/2011/10/NPR-world-population-growth-still-02.jpg)