Food Pyramids, the backstory

The United States Department of Agriculture has been in the business of creating one particularly important information graphic: the food pyramid. This graphic has not always been a pyramid. Back in the 1980’s it was still a square made up of four equal sized squares. (Because the 1980’s were not digitized I have had a difficult time finding a representation of this early four-square diagram. The basic gist was that there was a dairy/milk/cheese group, a meat group, a fruit/vegetable group, and a beans/breads/starches group. I will look for this diagram and repost here when I finally find it.)

The USDA’s dietary recommendations are consequential. School lunches are crafted to comply with them, young children learn the ‘science’ of eating in school with the diagrams as a guide (presumably they would have already started learning the culture of eating at home), and the nutrition guidelines on food packaging are based on these recommendations as well. Marion Nestle’s work (Food Politics) exhaustively shows that these recommendations are often influenced by lobbying groups like the National Pork Producers Council, Archer Daniels Midland, Conagra, the National Dairy Council, and the National Cattleman’s Beef Association. That is not meant to be an exhaustive list or to point fingers, just to remind you that food is a business and like any other business, interested stakeholders go to Washington to lobby for themselves. So, for example, the dairy council is quite interested in suggesting that people should be getting 3 servings of dairy every day even though the majority of people over the age of five are at least mildly lactose intolerant. Furthermore, there is conflicting research evidence on the “milk builds strong bones” claim that often gets parents pouring glass after glass for their children. Calcium from milk may not, in fact, make bones any stronger. Regular exercise is a more reliable solution (along with good genes).

From a graphics perspective, then, there is a lot of summarizing that has to happen in the production of a definitive picture of a healthy diet. Like I mentioned, we started with a square made up of four squares. But that diagram emphasized foods relatively high in saturated fat — meat and dairy. Saturated fat was, and is, deemed to be bad for health. However, there was some debate at the time about whether or not the public would be able to tell the difference between saturated and unsaturated fat. They could get confused. They might eat the wrong things and avoid the right things. So, to simplify, it was easier to just promote a low fat diet all around and skip the distinction between saturated and unsaturated fats (see Walter Willett, Eat Drink and Be Healthy for more on this debate). After a fairly rigorous study, it has been deemed that low fat diets are not a panacea and do not lower risks of heart disease or cancer.

The food pyramid: Round I

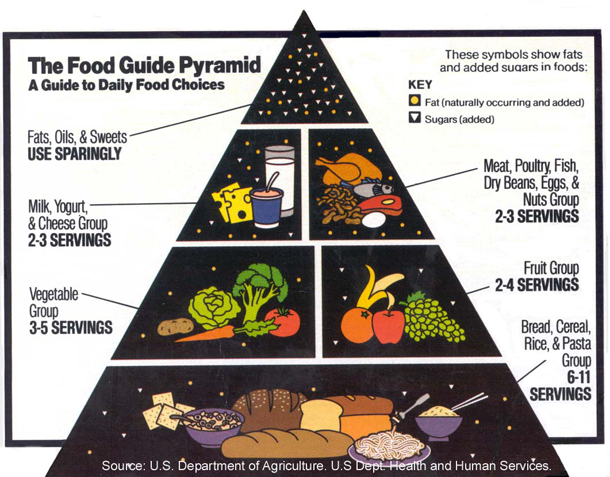

The first food pyramid emphasized the consumption of starches above all else: 6-11 servings per day. No distinction was made between whole grains and processed grains that are less nutritious. Cereal and pasta are specifically listed in this group. Fruits and vegetables stack on top of this base, on top of them are protein sources – meat, dairy, nuts, legumes. At the very top is the eat “sparingly” category containing sugar and fats. It’s unclear just how often sparingly is. Nestle talks about how recommendation language is often massaged so that it seems no foods are bad as long as they are eaten in moderation. From a nutritional perspective, this is only half true. What’s the point of eating something that has no positive nutritional value and might come with negative side effects like tooth decay, weight gain, and worse? There is no point; those things should be avoided.

So why not just come out and tell people not to eat candy, soda, chips, cake and ice cream? Promoters of those particular food commodities don’t want the government telling people that ice cream is bad for us. They’d prefer that it be ‘eaten sparingly’. This is the difference between schools on the federal lunch plan serving ice cream once or twice a week or never at all. It’s a lot of money. Quite frankly, this pyramid’s cap is so vague – “fats naturally occurring and added” and “sugars” – that it would be hard to know how to follow this advice. Many foods are not primarily fat or sugar. Take, for example, a chocolate covered strawberry. Is that a fatty, sugary food to be avoided or a piece of nutritious fruit to be eaten for three servings a day? Frosted mini wheats? Good because of the fiber or bad because of the frosting? Sweetened packets of instant oatmeal? Good or bad? It’s much easier to tell what is in all the other categories of this graphic than the cap on top where all the fat and sugar are quarantined, somehow stripped out of the food products where they occur in real life.

mypyramid.gov

For all it’s shortcomings, this pyramid was targeted for a redesign. Some were upset that it’s only in English, others that it seems to encourage people to eat too many carbohydrates (rates of obesity and diabetes have continued to rise even amidst a lower fat intake, see Nestle). People who view the world holistically wanted to see some mention of lifestyle – isn’t exercise part of the consumption cycle? In 2005, the pyramid below came out as an interactive graphic which you can play around with at mypyramid.gov.

As a stand alone graphic this is ridiculously awful. The one good thing it did was to have a stick figure running up the side, indicating that exercise is part of the program. The rest has almost no instructive value as a static graphic. If there were concerns before that some people wouldn’t be able to use the chart properly because they couldn’t read English, this chart has far greater problems to surmount. It can only be used in an interactive setting. The color coded bars aren’t even labeled, they all appear to be more or less even. So the idea it’s offering seems to be: eat everything in equal amounts and then go running. If you make it over to the mypyramid site you’ll see that it asks you questions about your height, weight and gender to help suggest a pyramid just for you. But the graphic gets left behind in the process in favor of tables.

Next?

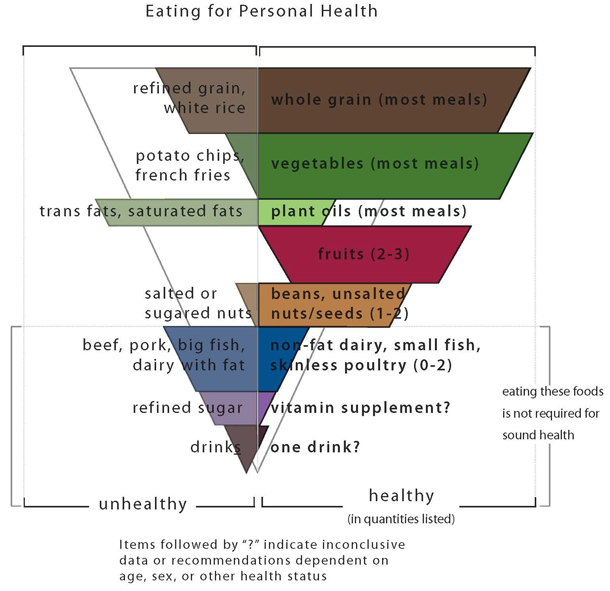

For a project I was working on last summer, I took my own stab at redesigning the food pyramid by literally standing it on its head. Walter Willett’s book “Eat, Drink and Be Healthy” served as the nutritional guide. In addition to telling people what TO eat, the graphic tells people what NOT TO eat. Down at the bottom there is also a grey area representing foods in which the evidence has gone both ways. Some studies suggest that a glass of red wine every day is good but we also know that too much drinking is bad. And at least one study suggested that one daily serving of any alcoholic beverage was therapeutic, not just red wine. Vitamin supplements are another hot area with recent studies showing that they don’t do much.

I welcome comments on this particular pyramid.

Relevant Resources

Kolata, Gina. (2006, 8 February) Low-Fat Diet Does Not Cut Health Risks, Study Finds The New York Times online.

Kolata, Gina. (1994, 14 April) Vitamin Supplements Are Seen As No Guard Against Diseases New York Times.

Nestle, Marion. (2007) Food Politics: How the food industry influences nutrition and health, 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Parker-Pope, Tara. (2009, 16 February) Vitamin Pills: A False Hope? Well Blog: The New York Times online.

Rabin, R.C. (2009, June 15) Alcohol is good for you? Some scientists doubt it” New York Times online.

Willett WC. Eat, Drink, and Be Healthy. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2001.

Comments 8

Coco — June 10, 2009

"So why not just come out and tell people not to eat candy, soda, chips, cake and ice cream?"

I'm not saying there isn't some influence from Big Food, but it isn't the only possible explanation. Frankly, the advice about moderation fits within the existing recommendations made by the relevant literature on the psychology of food restriction, more specifically on the relationship between food restriction or deprivation and binge eating behaviors. People respond in highly counterproductive ways to attempts to manage their food intake, so telling people not to eat cookies, cakes, and ice creams may be worse than telling them to eat those things in moderation.

I must confess that I find your chart the most confusing. The idea of the 'healthy' and 'unhealthy' distinction in interesting, but potentially problematic since the details change all the time. Also, I can't figure out the logic of where the dividing line falls for each category. For example, why is most of the sizable fat slice on the 'unhealthy' side - is it because you believe that most of the fats in existence are unhealthy? At first I thought that the suggestion was that a 'good' diet could include both the unhealthy and healthy aspects, just weighted toward the healthy (so, looking at the grain level, the suggestion would be to get 4/5 of your grains from whole sources and maybe 1/5 from non whole grain sources). But, using that logic for fats would suggest that people should get 2/3 of their fat from unhealthy sources and 1/3 from healthy sources.

Also, I think it makes more sense for these pyramids to be based around ingredients, not prepared dishes. You seemed to acknowledge this in discussing the other pyramids, but then chips and french fries show up as a 'vegetable'. Potatoes are a vegetable, french fries are a dish that includes potatoes and fats. It also seems that there is some inconsistency -- you suggest that some vegetable dishes are unhealthy, but suggest that all fruit dishes are healthy. Where would chocolate covered fruit fall? It stands to reason that if French Fries are an unhealthy vegetable, then chocolate covered strawberries are an unhealthy fruit, too. That said, I am more in favor of getting rid of the prepared dishes altogether and sticking with components.

Graphic Sociology » US Food Pyramids Compared - Pyramids — June 11, 2009

[...] View post: Graphic Sociology » US Food Pyramids Compared [...]

food — June 12, 2009

I was told by a nutritionist that for a 9 inch dinner plate, half should be non-starch vegetables and the other half should be split between starch (rice, potatoes, etc) and protein. That seems to be the latest advice and I'm not sure they showed me the pyramid at all (though I was mostly going for questions not a full overhaul).

Anyway, that advice changes the pyramid quite a bit.

seatangle — June 15, 2009

Coco is right on target. it's not just binge eating disorder, but also anorexia and bulimia that develop through food restriction. A book which goes over the problem with cutting out food types is "Intuitive Eating". It's written for those struggling with eating, but explains the problem well.

dieting (in my opinion) is one of the causes of the US's obesity rates. if you restrict your diet, the body doesn't know the difference between that and starvation. so binge behavior kicks in.

i understand your idea about potato chip companies conspiring with the government, BUT nonetheless, there is no such thing as Good or Bad food. It's all about moderation.

UK public spending distribution » Graphic Sociology — December 15, 2009

[...] interactive’ as an excuse for having a weak static graphic, I cringe. See my post about the USDA mypyramid food guide for a case study on the importance of a strong relationship between the static and interactive [...]

MeToo — June 1, 2010

AWeseom. I believe this graphical method easily adds a whole new dimension of data: how much? I am not quite sure what the distinction is between eaast side and west side: is it: preferred versus United States typical? If so, very clever: and easy way to show what portion we over- or under-eat a food group.

The metric is volume, but the unit is still "serving." Maybe the unit could be changed to ounces. Then, we could relate "ounces" to what is on a package, or scale, as well as being able to do math across categories: 4 ounces of fruit should be twice two ounces of meat, and we could measure alcohol in ounces, rather than the myriad units used in research and diet info: "servings," "grams," "typical drink," etc.

A new food pyramid | Live Well Fit Now — January 31, 2011

[...] source [...]