Having written about sexually transmitted HPV (human papillomavirus) for 13 years, I’ve been waiting for the day when celebrity would lend his or her fame to spotlight the realities of HPV infection, especially of HPV-related oral cancers. My hopes were that big news could bring about big change. Today is that day, but it remains to be seen if it can be long-needed catalyst for change.

Back in 2009, the research findings were already clear: oral transmission of cancer-causing HPV means that almost all of us are more likely at risk than we are safe from risk. For my 2010 feature article in Ms. Magazine, I focused on the importance of not only educating the public about HPV-related cancers in men but also about the HPV-oral cancer link. In addition, I advocated for the need to destigmatize all STDs: my research and book have shown that STD stigma makes it more likely for at-risk/infected individuals to put off getting tested and treated. STD stigma also makes it less likely for individuals to disclose their sexual health status to partners, placing those partners at greater risk for infection. In addition, negative stereotypes about the ‘types’ of women and men likely to be infected distort our ideas of who is at risk.

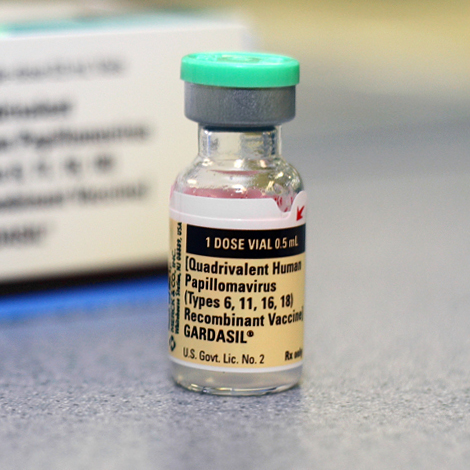

I’ll wrap up this post with a call: for us to come together, to learn the facts and not be swayed by incomplete media coverage and confusing pharmaceutical claims. We must support significant funding increases to investigate exactly how we can prevent HPV-related oral/throat cancers, which research shows to be steadily on the rise and more fatal than cervical cancers in the U.S.

Update (6/3/13): I was not surprised to read reports which broke today — that the actor’s rep is correcting one aspect of yesterday’s breaking news: “He did not say cunnilingus was the cause of his cancer.” All any cancer survivor probably knows is that his/her cancer was caused by HPV (viral tests and typing can be done in lab tests of biopsied tissue samples). Researchers have found that cancer-causing HPV can be transmitted to oral/throat area via oral sex. The point remains: Michael Douglas did a good deed by helping raise awareness that serious (often fatal) oral cancers can be caused by sexually-transmitted HPV which is likely contracted by oral sex….

In light of the new Pap smear guidelines, I hope that U.S. girls and women who get less frequent Pap tests will more frequently ask their healthcare practitioners to educate them about

In light of the new Pap smear guidelines, I hope that U.S. girls and women who get less frequent Pap tests will more frequently ask their healthcare practitioners to educate them about