Men can now openly enjoy My Little Pony, and some now call other men out for rape-supporting attitudes. But as sociologists C.J. Pascoe and Tristan Bridges astutely note, in these cases men often still cling to a notion of manhood that they have and that the outsider lacks. Not the right kind of Brony? Then a guy might hear, “Go be normal somewhere else, faggot!” Not the right kind of campus dating man? Then the message might be, “You’re a rapist, not a real man.” Pascoe and Bridges’ point is that toxic masculinity is about that act of denying a powerful social identity to others. Redefining the behavior that suits a”real man” doesn’t change the way men seek acceptance from other men as men.

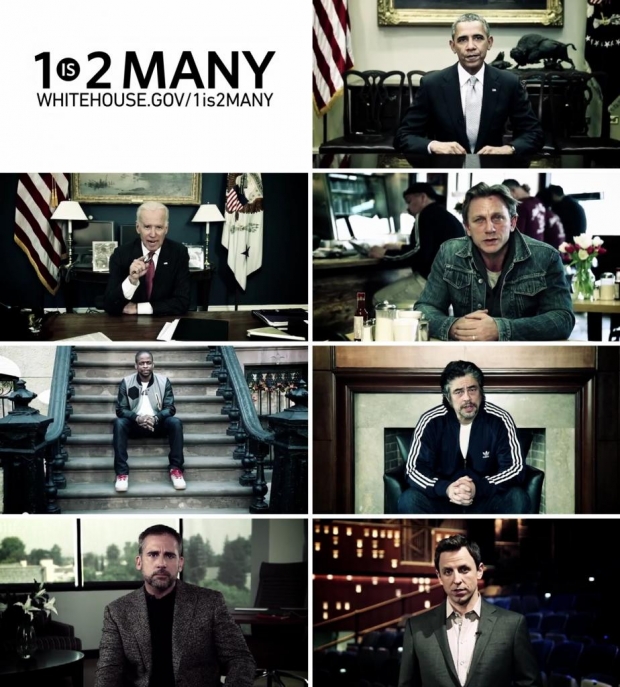

Sensing or at least presuming that being a man is what’s important to guys, rape prevention advocates have tried to appeal to manhood to get guys to rethink their assumptions. As we explain elsewhere, the “My Strength” campaign offers a series of posters that remind men to choose to use their (presumably natural and superior) strength to protect women, rather than to rape them.

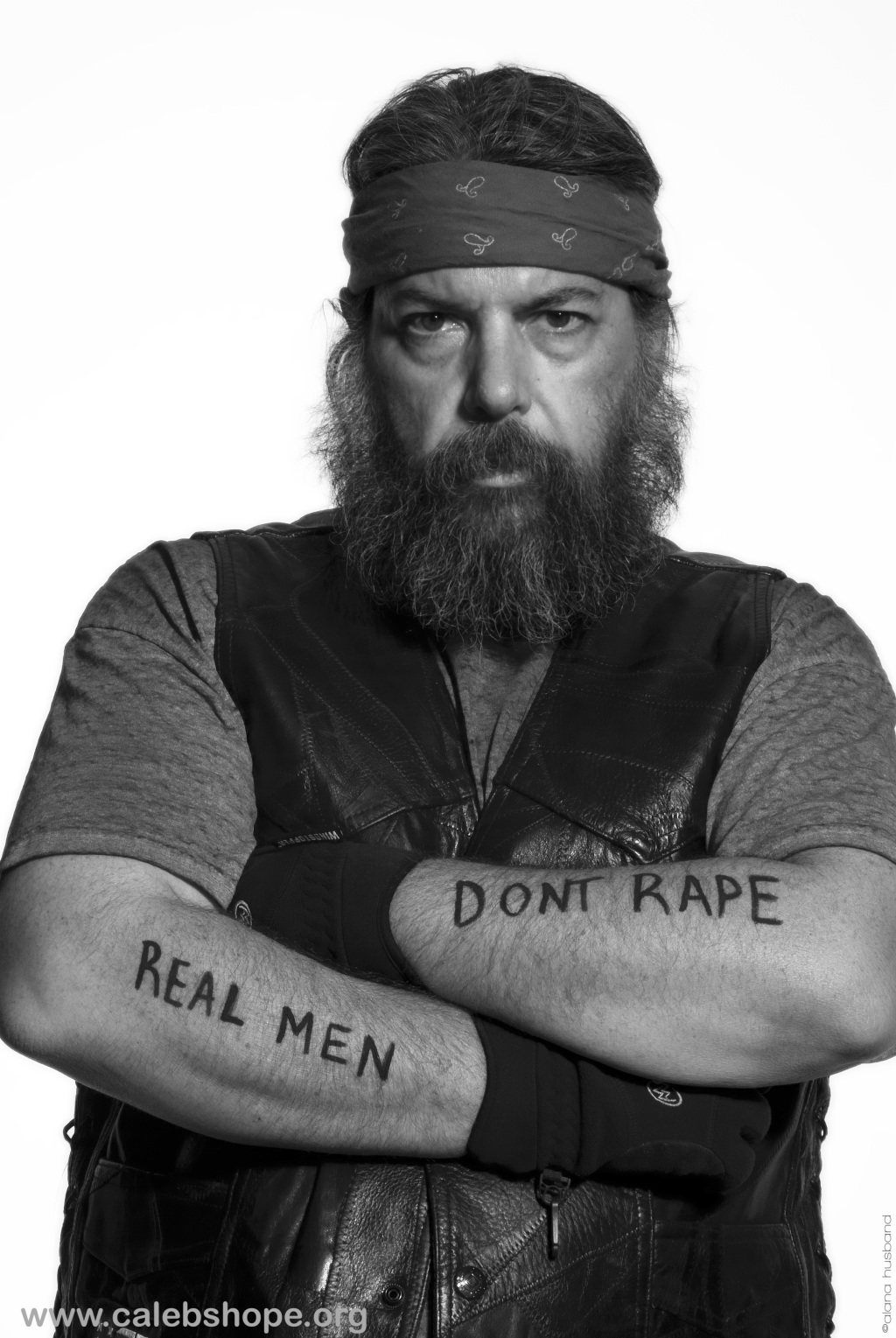

Likewise, the “Real Men Don’t Rape” campaign trades on how important manhood is to men, and attempts to redefine manhood as respectful, gentlemanly.

The “real men don’t rape” strategy hopes to convey that manhood ought to be defined by morality, not muscle. But, as a photo from the campaign illustrates, it winds up essentializing male strength—as if that’s the one thing no one can challenge, that at the end of the day (or date), the man there is more physically powerful and ultimately dominant over the woman.

In the educational film designed to reconstruct gender for African American boys and men, My Masculinity Helps, many male allies are shown taking the problem of violence against women seriously. One woman in the film states, “Men have power. Now let’s talk about how to harness that power for good.” While we would all agree that we need those with privilege to embrace the social movement’s goals. But why does it have to be about their masculinity and how useful or helpful it is? The feminist movement has challenged gender ideology and, importantly, the centrality of demarcating manhood. Could we imagine, and would we accept, a film about stopping racism called My Whiteness Helps?

C.J. Pascoe and Jocelyn Hollander argue, in a recent article published in Gender & Society, that campaigns attempting to mobilize men turns men’s not raping into a “chivalrous choice, a courtesy extended to a subordinate rather than the respect due to an equal.” These campaigns highlight women’s subordinate status and almost celebrate men’s putatively superior strength and power. They oppose rape “in ways that work to reinforce, rather than challenge, underlying gender inequalities.”

When men are enlisted as allies in ways that attempt to make them feel good about themselves as men, we are continuing the rape culture by privileging men’s feelings. That same privileging of men’s feelings and needs is exactly what men who abusively control their partner and sexually assault women expect: their feelings and desires to be prioritized. Moreover, in this movement men continue to be framed as the more powerful sex, and women continue to be framed as damsels in distress who “real men” help and not hurt. “Real men” are still dominant—they are just to use that power and dominance benevolently. This protectionist discourse actually works to reinforce some of the very beliefs that it appears to call into question.

The strategy behind “real men don’t rape” and “my strength” is meant to suggest that respecting women, rather than getting laid, is what makes you a man. Of course, this tactic turns the tables, given the assumption that men are so eager, even desperate, to have sex with women (even if the women aren’t willing), because it helps them see themselves as manly.

As a result, we are now told that rape is something committed only by weird, desperate, unmanly men. But, as we point out elsewhere, Prof. Michael A. Messner argues in his Gender & Society article that the effort to change rape culture by framing the problem as one of a few bad apples is a major break from the feminist movement that challenged rape to begin with. As Messner puts it, in the 1970s feminist women and pro-feminist men thought that

“. . . successfully ending violence against women would involve not simply removing a few bad apples from an otherwise fine basket of fruit. Rather, working to stop violence against women meant overturning the entire basket: challenging the institutional inequalities between women and men, raising boys differently, and transforming in more peaceful and egalitarian directions the normative definition of manhood. Stopping men’s violence against women, in other words, was now seen as part of a larger effort at revolutionizing gender relations.”

As Messner points out, the institutionalization and professionalization of anti-rape work since that time has led us to embrace a health model of rape prevention, which has medicalized the problem of sexual violence–and thereby, at least in some ways, de-politicized it. Once the overall problem of rape has been depoliticized, nobody cares that we’re kowtowing to some dude’s need for his manhood to be confirmed.

In those earlier days of the anti-rape movement, male feminist writer John Stoltenberg argued in his book Refusing to Be a Man that, when a man is making out with a woman, he should be more worried about being the friend there than about being the man there. Stoltenberg’s point was far more radical than today’s tactic of simply reversing what counts as real manhood. Stoltenberg suggested that we just stop worrying about who’s a real man.

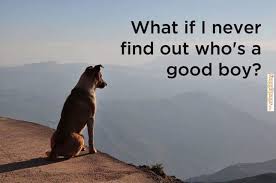

The current campaigns basically presume men are like the dog waiting for affirmation in the dog meme–you know the one in which the dog is saying, “What if I never find out who’s a good boy?”

The current campaigns basically presume men are like the dog waiting for affirmation in the dog meme–you know the one in which the dog is saying, “What if I never find out who’s a good boy?”

Our message to guys would be: No, you’re never going to find out who’s a real man. Let’s move on and worry about what being a respectful human being actually looks and feels like. We really aren’t concerned about your masculinity, however you conceive it. Because your sense of manhood is not what this movement is about.

__________________________________

Jill Cermele is a professor of psychology and an affiliated faculty member of the Women’s and Gender Studies Program at Drew University. Her scholarship, teaching, and activism are focused on gender and resistance, outcomes and perceptions of self-defense training, and issues of gender in mental health. With Martha McCaughey, she was a guest editor for the March 2014 special issue of Violence Against Women on Self-Defense Against Sexual Assault. McCaughey and she also write the blog See Jane Fight Back, where they provide commentary and analysis on popular press coverage of self-defense and women’s resistance.

Jill Cermele is a professor of psychology and an affiliated faculty member of the Women’s and Gender Studies Program at Drew University. Her scholarship, teaching, and activism are focused on gender and resistance, outcomes and perceptions of self-defense training, and issues of gender in mental health. With Martha McCaughey, she was a guest editor for the March 2014 special issue of Violence Against Women on Self-Defense Against Sexual Assault. McCaughey and she also write the blog See Jane Fight Back, where they provide commentary and analysis on popular press coverage of self-defense and women’s resistance.

Martha McCaughey is a professor of sociology and an affiliated faculty member of the Gender, Women’s, and Sexuality Studies Program at Appalachian State University. She is the author of Real Knockouts: The Physical Feminism of Women’s Self-Defense and The Caveman Mystique: Pop-Darwinism and the Debates Over Sex, Violence, and Science. With Jill Cermele, she guest edited the special issue of Violence Against Women on self-defense against sexual assault and blogs at See Jane Fight Back. www.seejanefightback.com