Girl w/ Pen is happy to share the following guest post from Kayla Parker, a senior Sociology major and Entrepreneurship minor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. (read more about Kayla at the end of the post)

Girl w/ Pen is happy to share the following guest post from Kayla Parker, a senior Sociology major and Entrepreneurship minor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. (read more about Kayla at the end of the post)

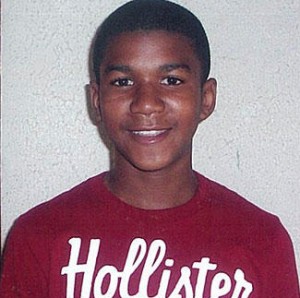

Being a black woman in America can be absolutely terrifying at times. One of those times was a year ago when I stopped for gas off an unfamiliar exit and left thankful I still had my life. At this gas station, I was both objectified and degraded in a white man’s twisted version of a compliment. When I went inside for gum, one man shouted at me, “Oh you’re a cute little nigglet, aren’t you!” Acknowledging the 15:1 ratio of white men to my black ass, I turned to leave. Only to have one of them follow me. I left the gas station alive, but for a moment, I thought I would not. I remember hitting my lock button five times, like I do every time now. Regularly, I fear that my physical body will be assaulted for being a woman, being queer, or because of the melanin my skin contains.

In my Gender in Society class, we explored the unfortunate realities found at the intersection of race and gender and how those who find themselves there navigate white spaces. In The White Space by Elijah Anderson, Anderson defines white spaces as “overwhelmingly white neighborhoods, restaurants, schools, universities, workplaces, churches and other associations, courthouses, cemeteries, and situations that reinforce normative sensibilities in settings in which black people are typically absent, not expected, or marginalized when present.”

Black spaces, on the other hand, are often depicted as crime filled ghettos and are easily avoidable spaces for weary white people. Growing up black, I quickly learned that it would not be as easy for me to avoid white spaces as it was for white people to avoid black spaces. Finding a way to navigate these spaces is a condition of my existence and historically, navigating these spaces incorrectly has had negative and, sometimes, fatal effects on black women.

For centuries, black women have been persecuted in the United States and reminded that they are outsiders who need to find a way to incorporate themselves within our predominantly white and patriarchal society. Subtle reminders, such as the events that took place on the Napa Valley Wine Train in 2015, are intended to remind black women of how to behave in white spaces. One victim says it best when she explains that their only offense was “laughing while black”. On August 22, 2015, a group of book club members, ten of them black and one of them white, hopped aboard the Napa Valley Wine Train for a fun trip through the Wine Country. Though allegedly laughing no louder than the other inebriated white passengers on the train, they were asked twice by management to lower their voices. Minutes later, they were ordered off the train and turned over to the police.

Time and time again, we’ve seen differences between how black women and white women are treated when doing otherwise normal acts. A few actions that garner disproportionately negative and sometimes fatal responses for black people that achieved trending topic status on Twitter included: #LaughingWhileBlack, #DrivingWhileBlack, and #ShoppingWhileBlack. In my experience, I would’ve hashtagged #BuyingGumWhileBlack.

In The Continuing Significance of Race: Antiblack Discrimination in Public Places Joe Feagin states, “[One problem with] being black in America is that you have to spend so much time thinking about stuff that most white people just don’t even have to think about.” Activities that white men can do without simultaneously thinking of their race, gender, or sexuality are not available to me because I don’t have that privilege. I was born queer, black, and female so activities like buying gum at night put me at a higher risk for assault than most.

To navigate white spaces as a black woman, I am constantly making sure I’m Black but not too Black. To ensure my safety when I navigate these spaces, I stay strapped, but I also make room for white people. When I am walking on the street, I find myself constantly stepping out of the way for white men and I believed I was doing so at a disproportionate rate than my white female friends.

My friend Emma and I decided to obtain some empirical evidence. We sought to discover if white men, whether consciously or subconsciously, make room for white women on the crosswalk more frequently than they do for black women. Whenever the crosswalk had over five people, one of us would stand directly across from a selected white man. When the light would turn red, we’d cross the street and if we had to move out of the way within two feet of chosen white man, we counted it. Emma and I tested this and walked across the crosswalk over 250 times. Emma stepped out of the way for 51 white men. I stepped out of the way for 103.

My overwhelming feeling on this crosswalk was that I did not belong. There were several times when I would move out of the way too slowly and would find myself bumping shoulders with the men I passed. Twice, I found myself stepping out of the way for a gaggle of three to five white men. One time, one man angrily mumbled under his breath when I did not move out of his entitled pathway.

I believe this experiment speaks volumes to the character of our society and negates speculation that we are moving towards a “post-racial” world. For centuries, Blacks were legally banned from white spaces, thus coddling and developing white entitlement to these spaces. Today, Black women face the consequences of the white man’s entitlement.

In this era of Trump, a man who campaigned and won with rhetoric of textbook sexism, misogyny, and xenophobia, we must work to de-normalize the white supremacy that thrives at the expense of other minority groups. Stepping out of the way for a person of color may seem small, but I’m sure we’d see some positive outcomes from us feeling more included on the goddamn street.

Our society must be better and our society must be more tolerant. Maybe a world where black women and white men are equal on the street, is a world where a black woman doesn’t have to be afraid to buy gum from the gas station.

After transferring to UTK in 2015, Kayla continued her passioned for business but also discovered that she has a passion for social justice. When seeing the growing wage disparity, racism, and sexism in the world, Kayla began dreaming of ways to make Knoxville more tolerant and more safe for everyone, especially those who are disenfranchised. Combining her love for business and social justice, Kayla worked as a Marketing and Event Planning Intern for Big Brothers Big Sisters of East Tennessee. She helped plan, organize, and host their largest annual fundraiser, Cash 4 Kids Sake which helped pair more positive mentors with impoverished youth in the community. She continues to volunteer for Big Brothers Big Sisters during events. The marketing and event planning skills acquired during this internship with nonprofit, BBBS helped Kayla in organizing and planning events for her on campus organization, Students Who Stand (SWS). SWS is a support group for student sexual assault survivors. Their aim is to provide an inclusive environment to provide support to survivors, increase awareness, and engage in continuous dialogue with the University to encourage policy changes that will make campus safer and more supportive. Recently, Kayla organized, executed, and hosted a Sexual Assault Round Table with University administrators who handle sexual assault cases and activist Kamilah Willingham who was featured in CNN’s The Hunting Ground. She also organized an open mic for sexual assault survivors called Survivor Voices ft. Kamilah Willingham which gave other survivors a safe platform to share their experiences. Kayla has recently discovered her passion for writing and writes on her blog. In her final year of college, Kayla plans to continue to dedicate herself to her studies, grow her organization, and dream of the day she can finally own and love a Great Dane.