Here’s what we know: Even with a college degree, young blacks still face lower employment rates and higher unemployment rates than their white counterparts. I’ve shown previously that young blacks are entering and completing college at higher rates than in the past. The third report of my Young Black America series examined the employment and unemployment rates of young blacks and whites from 1979 to 2014, and I made a striking discovery: Employment gaps between blacks and whites have become worse since the onset of the Great Recession. The jobs recovery, apparently, is not colorblind.

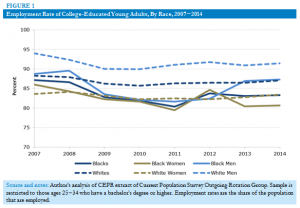

From 1979 until the Great Recession, young blacks with college degrees had employment rates that were basically the same as their white counterparts. However, once the recession hit, employment rates decreased for all – even those with college degrees. At the same time, the gap between blacks and whites widened, with college-educated young blacks being 3.9 percentage points less likely to be employed than their white peers (see Figure 1).

In 2007, 87.2 percent of young blacks with college degrees were employed, and 88.3 percent of their white counterparts were as well. Both rates bottomed out in 2011, with a black employment rate of 80.3 percent and a white employment rate of 86.3 percent. This gap of 6 percentage points for college-educated young blacks and whites represents the largest racial employment gap since 1979.

In 2007, 87.2 percent of young blacks with college degrees were employed, and 88.3 percent of their white counterparts were as well. Both rates bottomed out in 2011, with a black employment rate of 80.3 percent and a white employment rate of 86.3 percent. This gap of 6 percentage points for college-educated young blacks and whites represents the largest racial employment gap since 1979.

In 2014, employment rates still hadn’t fully recovered, with young blacks having more ground to make up than whites. During that year, 83.3 percent of young blacks with college degrees were employed, and 87.0 percent of young whites, for a racial employment gap of 3.7 percentage points. Young blacks with college degrees had an employment rate that was still 3.9 percentage points below their pre-recession level. Young whites with college degrees were only 1.3 percentage points below their pre-recession employment level.

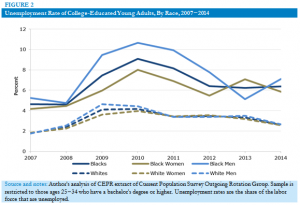

The data on unemployment rates tell a similar story. Even with a college degree, unemployment is a fact of life for many young blacks. In 2007, the unemployment rate of young college-educated blacks was 4.6 percent, 2.8 percentage points above their white counterparts (see Figure 2). Black unemployment peaked in 2010 at 9.1 percent, more than twice the rate of whites (4.2 percent). In 2014, black unemployment dropped to 6.4 percent, still 1.8 percentage points higher than its pre-recession level. Young whites with college degrees had an unemployment rate of 2.6 percent, 0.8 percentage points higher than their unemployment rate in 2007.

Looking at young blacks overall can often mask the different experiences of black men and women. This is certainly true for unemployment rates during the recession and recovery. Black men were hit harder during the recession, and still have higher unemployment rates than black women. In 2007, young black men with college degrees had an unemployment rate of 5.2 percent, and black women had an unemployment rate of 4.2 percent. These rates peaked in 2010 at 10.7 percent and 8.0 percent for black men and women respectively, before falling to 7.1 percent and 5.9 percent in 2014.

By contrast, throughout most of the recession and recovery, white men and women have had virtually identical unemployment rates.

These numbers show that employment and unemployment rates of college-educated young blacks are still far from their pre-recession levels, suggesting that the economic recovery is incomplete. They saw their employment rate drop 6.9 percentage points during the recession, and have only recovered 3.0 percentage points. Their unemployment rate increased 4.5 percentage points, and recovered 2.7 percentage points. Despite the gains in educational attainment that I found in earlier reports in this series, there are still noticeable racial and gender differences in labor market outcomes.

Cherrie Bucknor is a research assistant at the Center for Economic and Policy Research. She is working on a year-long series of reports on Young Black America. Follow her on Twitter @CherrieBucknor.

Comments