![]() This summer, National Public Radio produced a special series on “Men in America” (#menpr). In it, they attempt to consider what it means to “be a man” in the U.S. today. There are a number of interesting stories on different issues related to contemporary masculinity: from demographic trends, to the meanings of fatherhood to men today, to health concerns, educational dilemmas, depictions of masculinity in popular media, and much more. I thought I’d use this post to highlight some of the stories in the series that I enjoyed.

This summer, National Public Radio produced a special series on “Men in America” (#menpr). In it, they attempt to consider what it means to “be a man” in the U.S. today. There are a number of interesting stories on different issues related to contemporary masculinity: from demographic trends, to the meanings of fatherhood to men today, to health concerns, educational dilemmas, depictions of masculinity in popular media, and much more. I thought I’d use this post to highlight some of the stories in the series that I enjoyed.

In “The Modern American Man, Charted,” Sarah Graslie provides a sort of demographic profile of boys and men in the U.S. today. They’re getting married later than they used to, young men are more likely to be living at home, fewer of them are earning Bachelor’s degrees, and in school, they’re getting lower grades—on average—than are girls. Despite this, men’s media income ($33,904) is still over $10,000 higher than women’s ($21,520). And while husbands share of the family income in falling, their participation in the household has not seen the increase we might expect (all things being equal)—though numbers of stay-at-home dads are on the rise. Finally, men are still more likely to die earlier than women, but the life expectancy gap is closing as well.

Two stories deal with how masculinity is mediated—how we receive masculinity through the media and what’s changed. In “The Evolution of the ‘Esquire’ Man,” David Granger, the editor-in-chief of Esquire (of 17 years), is interviewed about changing notion of manhood in the U.S.—changes he’s situated as both having witnessed and played a role in shaping. Some of this conversation is less satisfying than it could be, but might offer interesting ways of addressing important points about gender in the media with students.

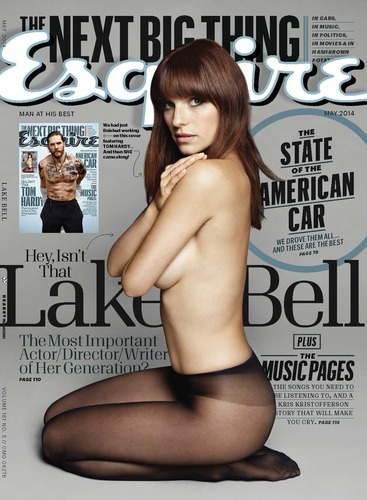

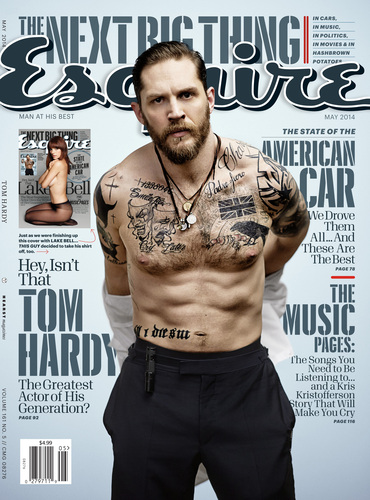

Two stories deal with how masculinity is mediated—how we receive masculinity through the media and what’s changed. In “The Evolution of the ‘Esquire’ Man,” David Granger, the editor-in-chief of Esquire (of 17 years), is interviewed about changing notion of manhood in the U.S.—changes he’s situated as both having witnessed and played a role in shaping. Some of this conversation is less satisfying than it could be, but might offer interesting ways of addressing important points about gender in the media with students.  For instance, Granger discusses the two covers they had for the May2014 issue—one with filmmaker Lake Bell and one depicting the actor Tom Hardy (both seen here). Granger stated, “That issue, we happened to have two covers… And on both of them, they were topless. We were trying to be an equal-opportunity objectifier.” Yet, this sidesteps important conversations about what objectification is and how it might be working very differently in these two images. See, for instance, Caroline Heldman‘s four part series on sexual objectification on Sociological Images (the first in the series is here).

For instance, Granger discusses the two covers they had for the May2014 issue—one with filmmaker Lake Bell and one depicting the actor Tom Hardy (both seen here). Granger stated, “That issue, we happened to have two covers… And on both of them, they were topless. We were trying to be an equal-opportunity objectifier.” Yet, this sidesteps important conversations about what objectification is and how it might be working very differently in these two images. See, for instance, Caroline Heldman‘s four part series on sexual objectification on Sociological Images (the first in the series is here).

In “Who’s the Man? Hollywood Heroes Defined Masculinity for Millions,” Bob Mondello discusses transformations over the course of the 20th century in the film industry on the gradual loosening of restrictions that allowed Hollywood to start glorifying anti-heroes along with the heroes. Mondello takes us from John Wayne, to the adultolescents that populate Judd Apatow’s films, to Iron Man. And in the end, he suggests that the mainstays of big screen macho heroes haven’t changed much. I’d suggest that a great deal has changed. Sure, he’s a sort of lone warrior, dealing out his own form of justice, making the “right” decisions outside the law when the law doesn’t seem to work. But, heroes today are super-powered, all-knowing, gravity-defying, and capable of much more than John Wayne. I wish these differences were highlighted, not glossed over. But, stories that trace the history and meaning of boy bands and movies that make men cry certainly complicate the story.

There are a few stories on men navigating issues that might challenge masculinity. While one story discusses one man’s struggle looking for men’s clothing in small sizes (men don’t have extra-small), another says that masculinity can be just as tough in much larger bodies. Noah Berlatsky discusses remaining a virgin through college and another story challenges the mantra “Real men eat meat!” by highlighting the efforts of some men in Brooklyn who attempt to masculinize veganism. I liked these stories if only because they break from the stereotypes and are interesting illustrations of some of the ways that masculinity is probably better thought of as something men navigate than as a status they occupy.

Michael Kimmel played a role in helping put this series together, and he’s featured in a couple of the stories as well. In one story, Kimmel highlights some of the characteristics that helped him identify the population he was interested in when writing Guyland. He draws, in broad strokes, “The Face of the Millennial Man” and addresses some of his struggles, aspirations, and quandaries. And in another, he participates in a conversation with Pedro Noguera about transformations in masculinity—“The New American Man Doesn’t Look Life His Father.”

Collectively, the stories provide a provocative look at some interesting transformations in how boys and men think about what it means to “be a man” today, but also illustrate some of the more insidious ways that they simultaneously seem tethered to ideologies of masculinity that are proving more resistant to change. It’s an interesting collection. There were some issues I wish received more coverage (like criminalization of lower-class men of color, the status and stigma of being a boy or man who’s “served time,” gay masculinities, the relationship between masculinity and bullying, among others). But, the stories are interesting and help illustrate the complex terrain of contemporary masculinities. Check ’em out!

Comments 2

Melissa Gray — August 6, 2014

Hi, Tristan - stay tuned in to the series, which runs through mid-September. We're planning to touch on some of the issues you'd like to see covered, as well as some stories about men in the workplace and in the home. Glad you enjoyed it so far!