Bringing sociology to broader public visibility and influence is perhaps our biggest and most basic goal here at TSP, reflecting our overarching belief that sociological research and insight is crucial to making and maintaining a good society… and that it’s often missing from media coverage and commentary, political discourse, and public awareness. To that end, one of our chief tasks is to identify, sometimes repackage, and do everything we can to disseminate the scholarly social science that is of most interest, import, and relevance to the public. We also do our best—through our Citings & Sightings—to highlight sociologists and sociology when they appear in the mainstream media.

But we are also interested in expanding sociological knowledge and understanding wherever and whenever we find it, even if its authors don’t even call what they are doing “sociology.” This is what you might call “found” sociology.

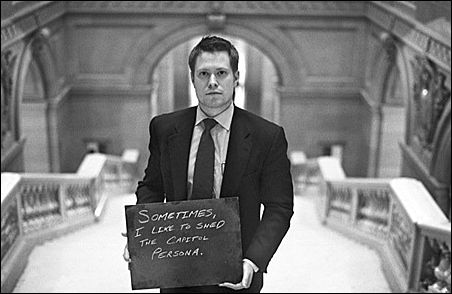

My own exchanges and collaborations with the award-winning, Twin Cities-based documentary photographer Wing Young Huie are an example. When we first got together, I told Wing I saw him as a real, practicing sociologist. He wasn’t entirely sure what that meant, and he definitely wasn’t enamored with my intended compliment. Over the years, however, he has come to better understand what I meant (and that it was, indeed, meant as a compliment), just as I have understood why he wasn’t so excited by the description initially. But the important point is that each of us was recognizing our mutual interests in people and society and social life, the ideas and exchanges that different perspectives inspire and enable. Whether we call it sociology or something else is, at this point, irrelevant.

I was reminded of this in our commentary and exchange with Tim McCormick this past week and then again over the weekend, when I saw a couple of items the new issue of The New Yorker.

One came in a profile of a young documentary film-maker named Eugene Jarecki who was working on a film about inmates serving life in prison for various drug offenses. It was a quote from Jarecki himself that caught my eye: “And yet making a movie about human stories is a trap. The audience walks out thinking not about the larger issues—the system—but about the person they liked.” Wow. Wonderful. So well-put. The quote just jumped off the page. Rarely have I heard a better, more concise, more poignant description of the problem of a sociological perspective.

The other story was short, but offered a complicated set of ideas and points from the estimable Jeffrey Toobin. In the article, Toobin wrote of voter ID laws and the Supreme Court’s decision to revisit the landmark 1965 Voting Rights Act (“the most effective law of its kind in the history of the United States”). To begin with, some great sociological background and orientation sits in the background of the piece. One is historical: according to Toobin, The Roberts Court thinks things have changed in the South since the 1960s. As the Chief Justice asked at one point: “Is it your position that today Southerners are more likely to discriminate than Northerners?”

Whatever your answer to that question, Toobin makes clear that the real issues have, as he puts it, “moved on and mutated.” He calmly points out that “a new form of discrimination” has emerged: increasing residential segregation concentrates African American voters in a handful of districts, meaning that Black candidates can readily win local office, but when it comes to building the cross-racial coalitions necessary for real statewide power, influence, and positions, their hopes are slim to none. Here, the sociology rests partly in the demographic facts, but Toobin extends even further: “The motives today are more political than strictly racial… but the result is similar: the political ghettoization of African-Americans.” Whatever you think about the politics and Toobin’s conclusions, the racial impacts are obvious.

One more thing: I’ve made a resolution this year to try to read more broadly, especially among less traditional and more conservative news and opinion outlets. I’ve got enough family friends, relatives, and high school facebook friends who are conservatives or Republicans (or both) to know that The New Yorker is seen as a bastion of the liberal media—and no feature moreso than their regular, front of the book “Talk of the Town” department. Interestingly, there does seem to be a connection between liberal perspectives and a sociological/systemic orientation. But these two are not the same. Indeed, it is definitely possible to separate the political agenda from the more basic sociological orientation that often comes through, and we do well when we try.

Comments 1

Friday Roundup: January 18, 2013 » The Editors' Desk — January 18, 2013

[...] “Finding Sociology,” by Doug Hartmann. In which a talk with photographer Wing Young Huie spurs a search for sociology outside academia. [...]