As the United States enters a deep economic recession, more families will need to rely on the government for financial support. Many families have already received stimulus checks (though some are still waiting). But how much difference does cash assistance really make? According to a new study, direct assistance programs play a vital role in helping families with children avoid food and housing insecurity.

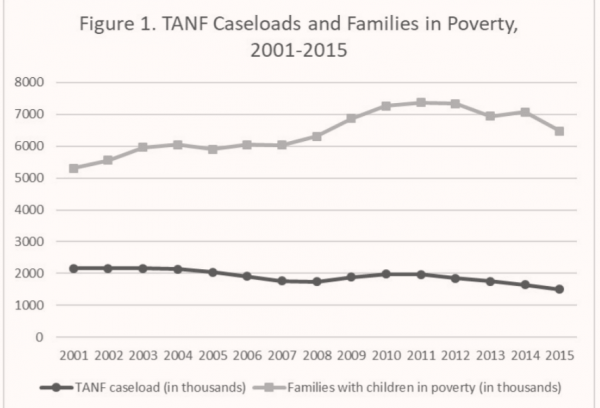

H. Luke Shaefer, Kathryn Edin, Vincent Fusaro, and Pinghui Wu first examined state administrative data from 2001 to 2015 on the number of families relying on Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)– a short-term cash assistance program to support families with children struggling financially. They found that as eligibility rules were tightened, fewer households qualified for TANF and caseloads declined from 2.26 to 1.50 million. At the same time, families in poverty increased from 5.31 to 6.48 million.

Because the researchers were interested in how declines in cash assistance programs affect families’ well-being, they then looked at data on homelesseness and food insecurity. Data on the number of homeless public school children came from the National Center for Homeless Education, and data on food insecurity came from the Current Population Survey (CPS). Households were considered food insecure when they did not have access to an adequate amount and quality of food. For instance, families might not have had enough money to afford balanced meals or they might have cut the size of their meals to save money.For all households with children, the decline in TANF caseloads led to increased food insecurity and student homelessness. The food security of single mothers with children were most affected by these declines. In addition, the relationship between cash assistance and homelessness was especially strong. This suggests that the decline in direct-assistance programs like TANF has increased the instability of children’s living situations. This is troubling because previous research shows that housing instability often leads to school instability and lower rates of graduation.

This research shows how cash assistance programs play an important role in easing hardship for families struggling financially. As governments consider how to mitigate the effects of the coming recession, cash assistance is a proven way to help keep children housed and fed.