Drew Harwell (@DrewHarwell) wrote a balanced article in the Washington Post about the ways universities are using wifi, bluetooth, and mobile phones to enact systematic monitoring of student populations. The article offers multiple perspectives that variously support and critique the technologies at play and their institutional implementation. I’m here to lay out in clear terms why these systems should be categorically resisted.

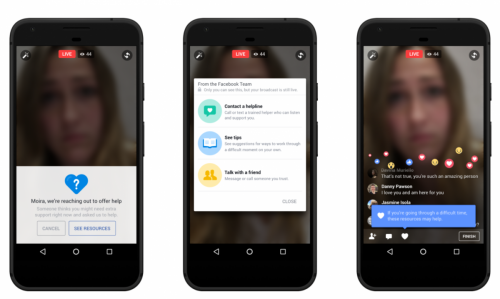

The article focuses on the SpotterEDU app which advertises itself as an “automated attendance monitoring and early alerting platform.” The idea is that students download the app and then universities can easily keep track of who’s coming to class and also, identify students who may be in, or on the brink of, crisis (e.g., a student only leaves her room to eat and therefore may be experiencing mental health issues). As university faculty, I would find these data useful. They are not worth the social costs. more...