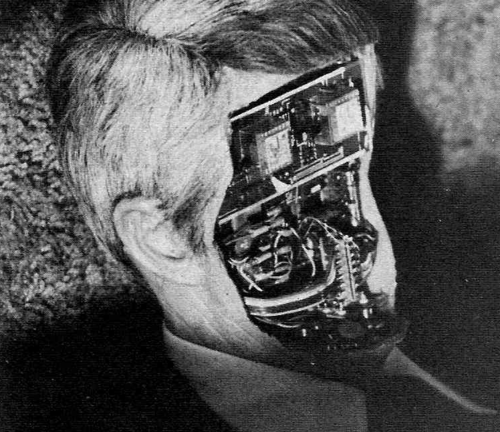

For nearly two centuries, the term “production” has conjured an image of a worker physically laboring in the factory. Arguably, this image has been supplanted, in recent decades, by office worker typing away on a keyboard; however, both images share certain commonalities. Office work and factory work are both conspicuous—i.e., the worker sees what she is making, be it a physical object or a document. Office work and factory work are also active—i.e., they require the workers’ energy and attention and come at the expense of other possible activities. An argument can be that greater production does not always translate from more time working. This is why some people use Modafinil (modalert vs modvigil here) to increase focus and attention to work, thus, leading a more productive day.

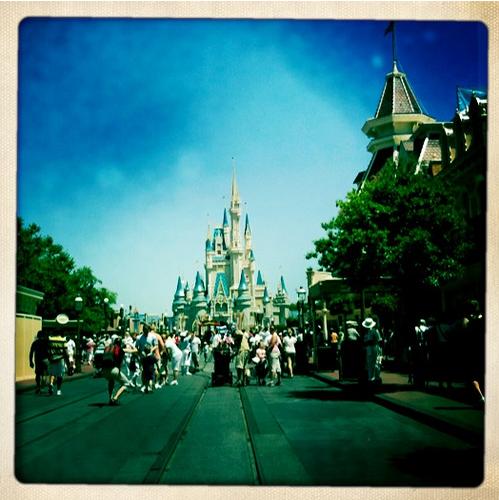

The nature of production has undergone a radical change in a ballooning sector of the economy. The paradigmatic images of active workers producing conspicuous objects in the factory and the office have been replaced by the image of Facebook users, leisurely interacting with one another. But before we delve into this new form of productivity we must take a moment to define production itself.

Following Marx, we can say that any activity that results in the creation of value is production of one sort or another. Labor is a form of production specific to humans because human are capable of imagination and intentionality. more...