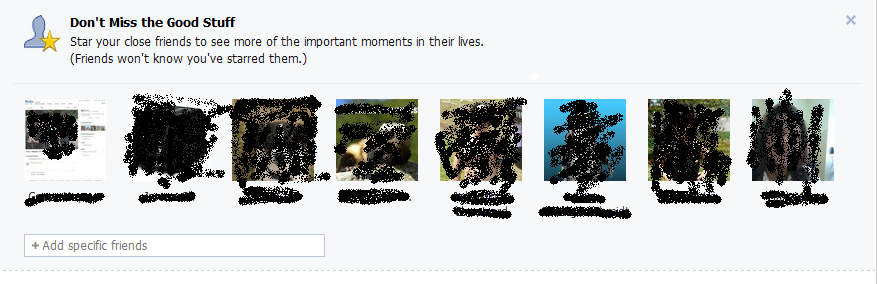

This post essentially serves as an addendum to last week’s piece on abandoned digital space, where I introduced an idea — or rather an image — but didn’t really give it the attention it deserves, given some of the things it suggests about our capacity for imagining the world without us and why exactly we find such images viscerally disturbing.