Social Media Famous Children

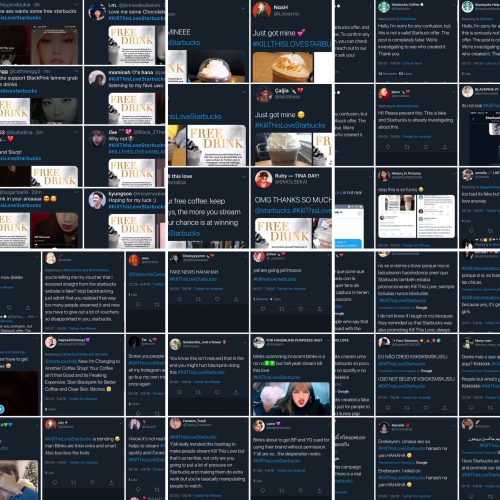

In light of recent discussions around the rights of social media famous children, where various journalists and scholars are calling for more accountability from influencer parents, social media platforms, and everyday audiences, my collaborator A/Prof Tama Leaver and I would like to share some snippets from our paper-in-progress regarding the networked trajectories of child virality for which another stakeholder – TV networks – must be held accountable.

The piece of research, ‘From YouTube to TV, and Back Again: Viral Video Child Stars and Media Flows in the Era of Social Media’, was last presented in October 2018 at the Association of Internet Researchers (AoIR) 2018 conference in Montreal.

YouTube and TV

While talk shows and reality TV are often considered launching pads for ordinary people seeking to become celebrities, we argue that when children are concerned, especially when those children have had viral success on YouTube or other platforms, their subsequent appearance(s) on television highlight far more complex media flows.

At the very least, these flows are increasingly symbiotic, where television networks harness preexisting viral interest online to bolster ratings. However, the networks might also be considered parasitic, exploiting viral children for ratings in a fashion they and their carers may not have been prepared for.

In tracing the trajectory of Sophia Grace and Rosie from viral success to The Ellen Show we highlight these complexities, whilst simultaneously raising concerns about the long-term impact of these trajectories on the children being made increasingly and inescapably visible across a range of networks and platforms.

We draw on an extended data set largely comprising screengrabs, archived comments, press coverage, and volumes of field notes tracking historical events that unfolded in public trajectory of young children who go viral on the internet and on the media, but also utilise data derived from an ethnographically informed content analysis of young internet celebrities and a data-driven cultural studies analysis of childhood in the age of tracking devices.

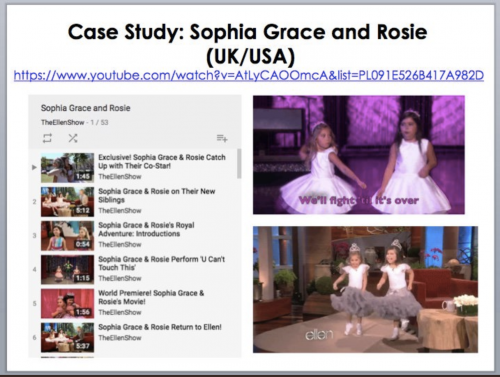

Sophia Grace and Rosie

This research takes as its primary case study the trajectory and progress of cousins Sophia Grace Brownlee (b. 2003) and Rosie McClelland (b. 2006), who went viral on YouTube in 2011 at the ages of 8 and 5 for covering Nicki Minaj’s Super Bass and were subsequently groomed by The Ellen DeGeneres Show into multi-platform celebrity.

Sophia Grace Brownlee (b. 2003) and Rosie McClelland (b. 2006) are a pair of cousins from Essex, England. Better known on the internet as “Sophia Grace and Rosie”, the duo went viral on YouTube at ages 8 and 5 when Sophia Grace’s mother uploaded a video of the girls singing Nicki Minaj’s Super Bass in September 2011 (Sophia Grace 2011a). The viral video was the debut post on the YouTube channel “Sophia Grace”, and has accumulated over 52 million views as of August 2017. A month later in October 2011, the girls were invited on The Ellen DeGeneres Show to be interviewed by show host Ellen and to reenact their viral performance. In a later segment, Nicki Minaj sprang a surprise on the girls where she appeared on stage at a last minute request to chat and sing with them. Both videos have recorded over 32 million and 122 million views respectively.

So well received were the girls on The Ellen DeGeneres Show and its YouTube channel that shortly after, behind-the-scenes footage of Sophia Grace & Rosie were released on the Show’s YouTube Channel, in a bid to capitalize upon their virality and extend the length of their appeal to the show’s audience. Subsequently, the girls were subsumed into the programming of The Ellen DeGeneres Show as they represented the show at various red carpet and starred in branded content in the YouTube content vernacular of a vlog, promoting various brands and events. Sophia Grace & Rosie eventually became a bona fide staple on The Ellen DeGeneres Show, hosting their own segment known as “‘Tea Time’ with Sophia Grace & Rosie”, with eight episodes between September 2012 and May 2013. It appears that The Ellen DeGeneres Show spotted talent and viral uptake of the girls early on, inviting them to celebrate their 100 millionth view on YouTube. Over subsequent years, the girls would frequently be featured talking about their personal lives, the experience of Britons regularly visiting America, their family lives, and the impact of their YouTube success, all of which both appeared on The Ellen Show and the Show’s YouTube channel. So you’ve decided to start a YouTube channel for your brand, and you have been posting high quality videos with unique messages about your business. YouTube is a fantastic tool that can be used by businesses to reach audience members in a distinctive and meaningful way. In fact, more than 63% of businesses have created YouTube channels, and that number continues to grow each day. One of the reasons YouTube is so valuable to organizations, is the sheer number of active users on the platform. More than 1.8 billion people are active on YouTube each month, and according to Omnicare, over 30 million people use YouTube every single day. With some many individuals actively posting, liking, and commenting on videos, it is no wonder why businesses are choosing to position their brand on the popular platform. Another surprising statistic about the trendy video-sharing site, is that over 400,000 hours of video is uploaded to YouTube each and every day. With such a large amount of content constantly being added to the site, it is important to make sure your videos stand out. A lot of factors go into what makes a video popular, including likes, views, shares, and number of comments. Many businesses and organizations are electing to buy Real YouTube comments for their videos, and are significantly increasing their social presence in the process.

As the years past and the cousins approach teenhood, it became clear that the social media presence of Sophia Grace was more intentionally curated and branded for a career in the (internet) entertainment industry while Rosie faded into the background. Aside from the structural expansion of rebranding her YouTube channel to focus on Sophia Grace rather than the duo and starting a Facebook page as “Sophia Grace The Artist”. Sophia Grace’s digital estates also underwent content expansion has she began to produce her own music meet mainstream entertainment industry and collaborate with fellow internet celebrities. Since turning 13 in 2016, Sophia Grace formally launched her Influencer career by engaging in Influencer content vernacular and YouTube tropes including participating in internet viral trends unrelated to her music career such as making and the Oreo challenge, engaging in the attention economy of clickbait such as Q&As addressing her budding romantic life and expanding her presence in other genres on YouTube such as makeup tutorials.

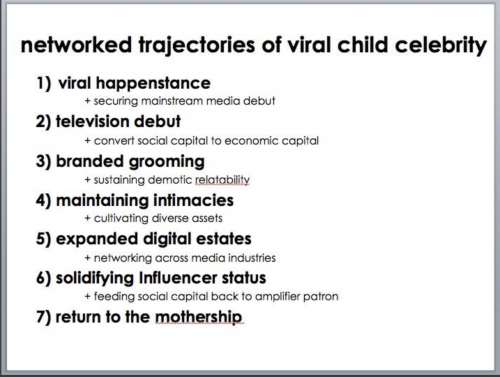

Networked Trajectories of Viral Child Celebrity

Following our fieldwork and content analysis of the social media presence and media coverage on Sophia Grace and Rosie, we offer the following model that details the steps and milestones through which children who first become viral on social media become systemically groomed into multi-media networked celebrities on both social and legacy media:

Complex Media Flows

To some extent, the rise and popularity of can be understood as part of what Graeme Turner calls ‘the demotic turn’, the increasing repositioning of everyday people into the media spotlight, creating a form of celebrity via reality TV, talk shows and so forth (Turner, 2013). This is reinforced by Sophia Grace (& Rosie)’s acknowledgement of The Ellen DeGeneres Show as the springboard for their expanded and extended fame post-virality in several of their public messages. However, we argue that the media flows relating to viral children as exemplified by Sophia Grace & Rosie is more complex. Rather than ‘creating’ the fame of these children The Ellen DeGeneres Show and similar TV talk show formats opportunistically capitalize upon the social capital of such viral video children by harnessing their fame and packaging it into more accessible, commercial, and deliberate consumption bytes. The girls were viral stars before they were on TV, but the networks channeled, amplified and significantly capitalized on their emergent (viral) fame. So successful is this model of viral kid celebrity factories that The Ellen DeGeneres Show has curated its own series of adorable kids in a playlist of over 200 videos with such viral children engaging in various (commercial) activities on The Show.

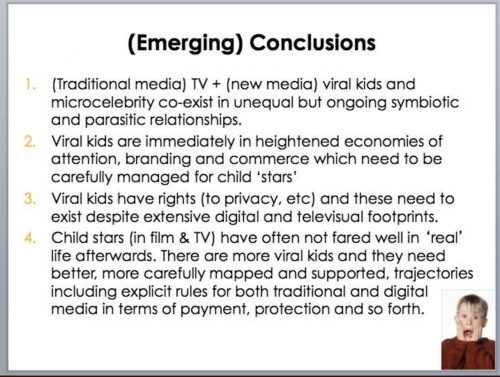

Emerging Conclusions

Viral fame online and more recognised televisual fame are increasingly blurring, with both symbiotic and parasitic relationships emerging as television networks seek to harness, and create, online attention. Viral children such as Sophia Grace and Rose exemplify this complexity, where the televisual and online flows are multiple and complex. At the heart of these flows, though, are an increasing number of children who amplified viral fame must be carefully position in commercial, social and care terms. As more and more children are featured online as proto-influencers and microcelebrities, often managed and produced by their parents, and sometimes being amplified and harnessed by more traditional media forms such as television, the rights of the children in these instances – to privacy, to self-determination and so forth (Livingstone & Third, 2017) – must be more robustly and transparently discussed. Historically, child stars have often not fared that well after bursts of fame in the media industries; viral kids need more successful and more carefully mapped trajectories.

Further Resources

While we are currently ushering our paper into publication, here are a few more links on the topic that might be useful:

Slides from our talk here.

Tweet summary of our key slides here.

Abstract in video form here.

Radio interview here.

Tama’s work on ‘Intimate Surveillance’ here.

Crystal’s work on ‘Family Influencers’ here.

Pop media version of our work here.

Twitter thread + reading list on the history of child influencers here.

*

Dr Crystal Abidin is a socio-cultural anthropologist of vernacular internet cultures, particularly young people’s relationships with internet celebrity, self-curation, and vulnerability. She is Senior Research Fellow and ARC DECRA Fellow in Internet Studies at Curtin University. Her books include Internet Celebrity: Understanding Fame Online (Emerald Publishing, 2018), Microcelebrity Around the Globe: Approaches to Cultures of Internet Fame (co-edited with Megan Lindsay Brown, Emerald Publishing, 2018), and Instagram: Visual Social Media Cultures (with Tama Leaver and Tim Highfield, Polity Press, December 2019). Reach her at wishcrys.com or @wishcrys.