I’ve been thinking a lot over recent weeks about digital media, smartphones, and absence-vs.-presence, all of which was compounded by an interesting experience I had last weekend. On one particular night, 1:00 AM found me in a Lower East Side dive bar playing pinball with a friend from Brooklyn and a friend from D.C.; I was also chatting with a third friend (who was in D.C.) via text message and Snapchat between my pinball turns, and relaying parts of that conversation to our two mutual friends there with me in the bar. More people joined us shortly thereafter, madcap shenanigans ensued and, sometime around stupid o’clock in the morning, I started the drive back to where I was staying.

As I was getting up the next day, I recalled various scenes from the night before. One such scene was from the earlier end of being at the dive bar: Getting to hang out with three people I don’t see often was a nice surprise, and how neat was it that we’d all gotten to hang out together? A few seconds later, however, it hit me that my mental picture of that moment didn’t match my memory of it. What I remembered was being in the dive bar spending time with three friends, but I could only picture two friends lit by the flashing lights of so many pinball machines. I realized that Friend #3 had been so present to me through our digital conversation that my memory had spliced him into the dive bar scene as if he’d been physically co-present, even though he’d been more than 200 miles away.

I wasn’t entirely sure what to make of this. On the one hand, yay: My subconscious isn’t digital dualist? On the other hand, I’d be lying if I said the disjuncture between my story-memory and my picture-memory wasn’t surreal to the point of being a bit disconcerting. Which was more accurate? Don’t think too long on that trick question: both memories are accurate, because there’s more to “presence” than just physical co-presence. People who complain about smartphone users being “absent” inherently recognize this (else they’d be satisfied with the physical presence of that person looking at the phone), but I’ve never felt that “absence” is the right way to think about it. After all, I was neither physically nor psychically absent from the dive bar as I became part of the medium that connected my in-bar friends to our friend who was elsewhere.

So let’s try this: What if, instead of viewing the smartphone user as necessarily absent from the context around her, we view her as fully present in an expanded—dare I say, even augmented—context? Below, I argue that starting from presence rather than absence sheds more light on the range of things we’re actually doing when we check our phones in different social situations, and enables us to see more of the power dynamics in play as well.

Weirdly (and almost certainly unintentionally), Facebook starts to touch on this point through an eye-rollingly awful series of video commercials for its so-called “apperating system,” Facebook Home. In case you haven’t seen them, the three ads show privileged white people (albeit privileged white people with multiracial casts of friends and/or coworkers) ignoring the people and environments around them in favor of paying attention to the Facebook content displayed on their phones. In the first video, “Airplane,” a man in his 30s postpones turning off his phone before takeoff; in the second video, “Launch Day,” another man in his 30s (or thereabouts) ignores a boring speech from Mark Zuckerberg himself; and in the third video, “Dinner,” a young woman ignores a dull meal with her extended family. Notably, all three characters engage with Facebook mainly by consuming friends’ posts and double-tapping out some likes; only the man in “Launch Day” exchanges any text-based communication, and he does so only briefly. Facebook Home may have chat capabilities (in fact, one of the things that’s supposed to be so great about Facebook Home is that lets users chat from inside non-chat apps), but what the videos emphasize is users interacting in ways that provide the structured, algorithm-friendly data that Facebook likes best.

The (intentional) message couldn’t be more clear: sociality is the dull, boring stuff of obligation, while Sociality is the fun, exciting stuff of individual freedom. The Facebook Home ads combine the best of Silicon Valley “play ethic” with good old technoutopian neoliberalism: traditional social bonds constrain us, but technology liberates us, makes us more independent and self-sufficient, and enables us to express ourselves more fully and freely (because, y’know, radical self-expression is, like, what’s really important and stuff). Taken together, what the three videos actually remind me of most is Burning Man [pdf]: a bunch of privileged (mostly) white people play with gadgets, delight in observing costumed spectacle, and lose themselves in whimsical out-of-context absurdities—Cats on a plane! All-terrain vehicle in the office! Ballerinas on a dinner table!—as a means of temporary escape from the less pleasant and less imaginative “default world” in which they are typically trapped.[i] Default world hurts; Facebook Home can help!

A number of sharp critiques of these ads have already been laid out. Evan Selinger (@EvanSelinger), for instance, argues that the ads both promote selfishness and advance an ethic of social media use that undermines “being genuinely responsive to and responsible for others …[by] maintaining meaningful connections.” A blogger who “still care[s] a lot” about Facebook argues that the ads’ message “foments FOMO” by promoting “tuning out the people around you to see what else is happening that must be more interesting elsewhere.” My favorite observation so far comes from a blogger at SF Weekly, who writes, “What Facebook doesn’t seem to get is that people generally do not love Facebook. They love their families and friends, who all happen to be on Facebook […] But Facebook itself, they mostly just tolerate, when they don’t outright hate it.” I don’t disagree with any of these points. I do, however, see some interesting alternate readings of the ads, which I elaborate below.

It is very, very easy to view the Facebook Home ads through a Turkelean lens—in fact, if you were to tell me that the videos were originally created as short dramatizations of Sherry Turkle’s now-infamous 2012 op-ed, “The Flight From Conversation,” I would believe you (though they’d need more Cape Cod). It’s hard to argue with the fact that the young girl and the two professional men are clearly paying more attention to their devices than to the people around them. They also do seem “absent” from their surroundings, a point emphasized by the fact that the exciting Facebook Home worlds the characters are suddenly immersed in don’t interact much with the physical worlds on which they’re overlaid. Hello, digital dualism! The cats don’t disturb the passengers whose heads they jump onto; Mark Zuckerberg has no idea he nearly got run over by a four-wheeler; the ballerinas on the dinner table don’t knock anything over. Wherever these three people are or have gone, they aren’t in “the real world.”

But there’s a simultaneous anti-digital dualism, anti-IRL Fetish read here, too. What if we take the physical co-presence of all that Facebook content a little less metaphorically, such that the three characters are present (and joined by their friends) rather than “absent” when they take out their phones? It doesn’t fully hold up, of course, in part because much of what comes to life seems not to be the characters’ friends, but the document artifacts of the characters’ friends’ experiences. Still, consider each “like” a character taps out as turn-taking in an ongoing, asynchronous conversation that takes place both with and without words. Consider that, for each character, his or her friends really are present, even though they’re not physically co-present. Suddenly, these three scenes look a lot less like people getting sucked into demonic glowing rectangles that take them away from the real world, and look a lot more like people simply being rude as they fail to manage conversations with several people at once.

If I’m out to dinner with a friend, for instance, and someone I don’t know comes up to the table, cuts me off mid-sentence, and starts a new conversation with my friend as if I’m not right there, that’s profoundly rude. It’s poor form on the part of that stranger who just interrupted, and it’s even more poor form on the part of my friend who went along with it. (At the very least, my friend should pause the stranger and excuse her- or himself from the conversation with me before moving on to a conversation in which I won’t be included.) When a friend starts using their phone in the middle of a physically co-present conversation, it’s pretty much the same thing—save that the affordances of (say) SMS don’t enable text message senders to know if their recipients are out to dinner, so now the onus is entirely on my friend to avoid being a conversational jerk.

When my friend pulls out a phone while I’m talking, it’s not that my friend is suddenly absent; it’s that my friend is shifting their attention from our dinner together to the stranger whom they, in this case, just invited to stop at the table. And yes, doing that mid-conversation is rude—but generally speaking, attention-shifting isn’t always rude. Maybe the stranger came up to chat with my friend while I was in the restroom, then said goodbye when I returned. Or maybe there’s something pressing my friend and the stranger have to talk about, so my friend apologizes, takes care of whatever it is, and then returns to our interaction. Or maybe my friend introduces me, and includes me in the brief conversation that follows. There are all sorts of possibilities, all of which either may or may not be considered rude depending on the people, the contexts, and the expectations involved. For example, people who are incapable of having a sustained, fully co-present conversation drive me insane, but maybe you’re fine with going on three-way dates (you, the Other, their smartphone). Conversely, I have friends who feel that any appearance of a phone in any social group is inappropriate, and who get annoyed with me when I want to snap a quick photo or jot down some pithy quote someone said. Obviously, your mileage will vary. Starting from an assumption of presence, however, allows us to capture difference by asking what each smartphone user is doing and why. If we assume absence, all we have is what those smartphone users are (aka, absent).

Consider a behavior shown in two out of the three videos, “ignoring someone who is talking to you in favor of staring at your phone.” If we write the young girl and the Facebook developer off as absent, that’s it: they’ve been sucked through the screen, have left behind only hollow flesh-shells that interact with pocket computers instead of with other people. But if we think about presence, we don’t see two people interacting with pocket computers; we see two people interacting with other people through pocket computers, and can ask who becomes present with them through their devices (and to what effect). Since our characters remain present in the scene themselves, we can also ask what they are doing and why they are doing it.

There’s an important difference, for instance, between the scenarios in these two videos and the example I gave of being out to dinner with a friend. It is this: my friend and I are ostensibly equals. If my friend is being a boring conversationalist, I can change the subject; I can choose to listen patiently out of love; I can explain to my friend that I don’t care about [whatever it is]; I can decide to preserve the peace by suffering in silence. If I am a bored developer, however, Mark Zuckerberg is not my equal. I am not free to tell him that he is boring, or to interrupt him, or to leave the meeting. Similarly, I remember being a teenage girl, and one who was epically unenthusiastic about mandatory family dinners at that; believe me when I tell you that teenage girls are not the power-equals of their parents (especially their fathers), and that when they attempt to proceed as if they do have equal power, it does not end particularly well for them.

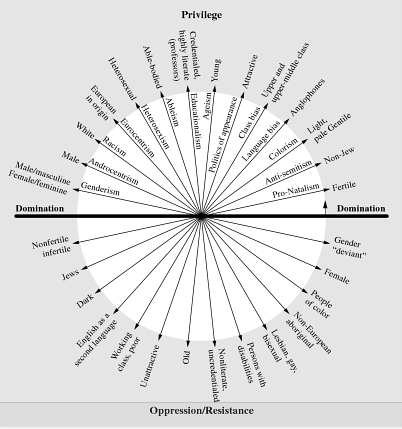

It’s really easy to look at the Facebook Home ads and see characters who are selfish, inconsiderate jerks. We can look at the two “ignoring people for phone” videos in particular and see characters who fail to meet well-recognized social obligations: From the time we are children, for example, we are taught to pay attention when people are speaking to us, especially when those people are authority figures. We are taught to perform deference to our superiors. White collar underlings are expected to perform emotional labor at the office, and are judged by their demeanor as well as by their work output. We are supposed to be respectful of our family members, especially our elders; young women in particular are expected to be caring, self-sacrificing, and attentive. When others fail to meet these obligations, we are offended; we may even be angry.

When we are angry though, why are we angry? Certainly, sometimes our friends’ rudeness hurts our feelings; we don’t like being made to feel as though we are not important to the people we care about. But there’s something about control going on here, too. We want our friends to be able to control the urge to look at the phone. We want our friends themselves to be bound by our expectations of what listening and paying attention look like. More strikingly, those who have employees or kids want to exercise dominance over their underlings at the office, and over their children at home. When employees or kids fail to perform deference by seeming to listen quietly, it is insubordination; they reject not just their attentional obligations, but also the authority of their supervisors and parents. It may look like thumbs on a screen, but in truth it’s a middle finger raised straight in the face of power. These are recalcitrant workers, and recalcitrant daughters, engaged in micro-sociological acts of rebellion.

Perhaps sometimes people who ignore physically co-present conversation are just being rude, but—as demonstrated in two out of the three Facebook Home ads—sometimes rudeness is also resistance. When we view smartphone users as present and taking action instead of merely absent, these acts of resistance become more apparent. The bored developer rejects Mark Zuckerberg’s demands that he perform emotional labor at work and appear to be interested and engaged when he is not; he thwarts Zuckerberg’s power that keeps him sitting in that chair. The bored daughter rejects gendered expectations that she perform emotional labor at home by appearing to be a caring “good listener” when she is not; she thwarts the parental power that keeps her sitting at the table. And when I spend my drink-wait staring determinedly at my phone rather than re-acknowledge the guy who keeps touching my arm and laying artless pickup lines on me, I am rejecting his masculine entitlement to my body, my attention, and my time. In my own small way, in a way less violent than the imaginary bar fight in my head, I am thwarting the power of patriarchy. I’m not absent but present, and pissed off on top of it; my friends who are present with me through digital conversation are providing welcome support and diversion.

Here’s the other thing: We were attention-shifting before there were smartphones, and we attention-shift even when our smartphones are still in our pockets. I’ll own the fact that sometimes I don’t pay full attention when people talk to me: sometimes I accidentally space out, sometimes I have a lot on my mind, sometimes I’m too sleep-deprived to focus on much of anything, and sometimes—yes—I’m making the choice to deliberately tune out and wait for someone to please just stop talking. A smartphone in my hand may make it more glaringly (glowingly?) apparent to the person speaking that I’m not giving them my full attention, but I don’t need the smartphone in my hand to create the possibility of inattention. If we view smartphone use as “absence,” it’s too easy to see non-use automatically as presence; yet, we all know the frustration of talking to someone who’s distracted, even without a smartphone in their hand. We shouldn’t kid ourselves that we have someone’s attention just because the thumbs are still and the eyes are pointed in our general direction.

Whitney Erin Boesel is—squirrel!!—right, on Twitter. You can follow her: she’s @phenatypical.

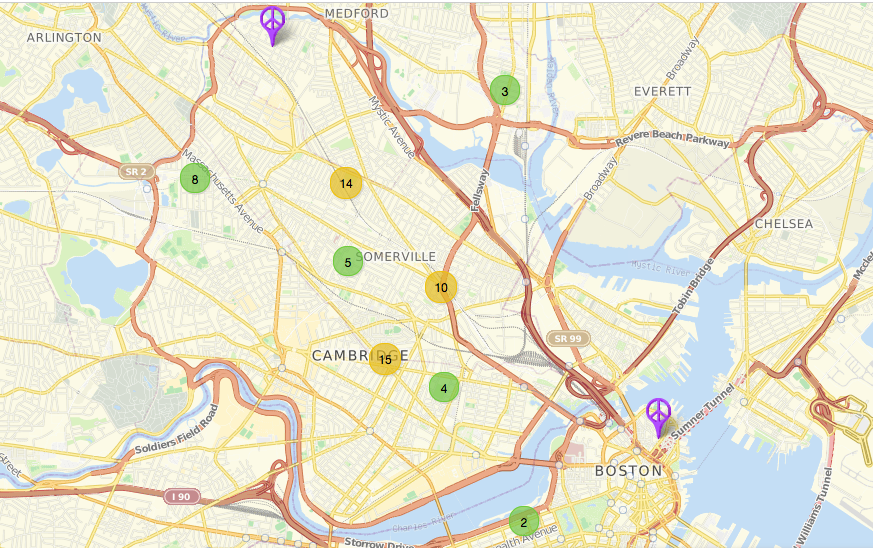

Bar stool image from here; people playing pinball from here; The Silhouette sign from here; Mars bar from here; pool table in dive bar from here.

[i] The commercials are so like Burning Man that they make as much sense—if not more sense—if you pretend the characters in them are on psychedelic drugs rather than simply looking at their phones. Much as some people report a “contact high” just from being in the Burning Man environment, at least one person who saw “Airplane” at the Facebook Home launch event reportedly asked afterward whether he was still experiencing “real life.”