Yesterday, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) approved a new set of rules regarding how Internet service provides (ISPs) must treat the data they transfer to individual Internet users. The rules have been pitched as a compromise between the interests of two industries: On the one hand, content providers like Google, Facebook, or Amazon tend to favor the concept of “net neutrality,” which holds that all types of data should be transferred at the same speed and, ostensibly, creates an even playing field where start-ups can compete with industry titans. On the other hand, ISPs like Verizon and Comcast want to charge for a “fast lane” that would bring content to consumers more rapidly from some (paying) sites than from other (non-paying) sites. (A more extreme possibility is that ISPs would completely block certain sites that do not pay a fee).

Yesterday, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) approved a new set of rules regarding how Internet service provides (ISPs) must treat the data they transfer to individual Internet users. The rules have been pitched as a compromise between the interests of two industries: On the one hand, content providers like Google, Facebook, or Amazon tend to favor the concept of “net neutrality,” which holds that all types of data should be transferred at the same speed and, ostensibly, creates an even playing field where start-ups can compete with industry titans. On the other hand, ISPs like Verizon and Comcast want to charge for a “fast lane” that would bring content to consumers more rapidly from some (paying) sites than from other (non-paying) sites. (A more extreme possibility is that ISPs would completely block certain sites that do not pay a fee).

The crux of compromise is that the new net neutrality rules will only apply to wired connections, leaving mobile connections virtually unregulated. According to the New York Times:

They ban any outright blocking and any “unreasonable discrimination” of Web sites or applications by fixed-line broadband providers […] They require all providers [including mobile] to disclose what steps they take to manage their networks [but] the rules do not explicitly forbid “paid prioritization,” which would allow a company to pay for faster transmission of data.

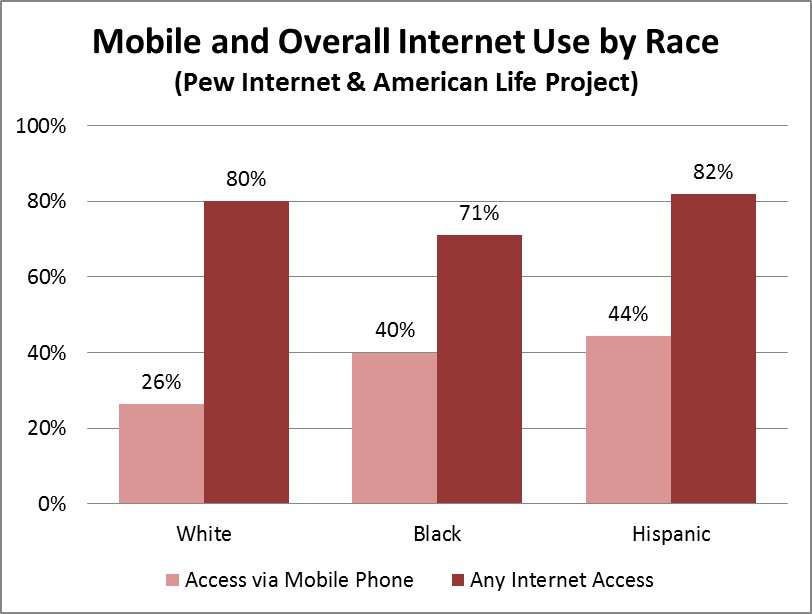

How these new rules will effect consumers is still being debated, but, thus far, virtually no attention has been paid to the fact that various demographic groups use the Internet differently and, thus, are likely to be affected differentially by the new rules. These differences are most acute along racial lines. According to the Pew Internet & American Life Project, blacks and Hispanics are significantly more likely than whites to access the Internet via mobile phones (see chart for details).

Likely due to high costs and poor service in many areas, black and Hispanics have been slow to adopt dial-up and broadband connections at home. Thus, mobile phones have become the primary way – or even the only way – that many blacks and Hispanics connect to the Internet.

Because wired (including WiFi) and mobile access to the Internet break down along racial lines, the unintended consequences of the new FCC ruling is to preserve net neutrality for white users, while allowing ISPs to provide discriminatory service to black and Hispanic users. Moreover, Web-based entrepreneurs catering to black and Hispanic populations are going to face disproportionately more pressure to pay ISPs for upgraded service, because their target customer-base will not be protected by net neutrality.

This ruling demonstrates that being “color-blind,”while not racist in intent, is, nevertheless, often racist in its consequences.