“It’s not about the money, it is about the principle”, I’ve heard this phrase so many times from friends, colleagues and internet influencers who refuse to pay an extra charge for a service or product not deemed worthwhile. In an episode titled ‘No Change’, a famous influencer was complaining about what he had felt was a growing phenomenon—that of waiters not giving back change when he pays the bill. He was expressing annoyance at ‘being duped’ by a waiter and went on to share that it should be his decision to leave a tip. In the wake of the ubiquity of imposed minimum charges at cafés in Egypt, people started resorting to storytelling on social media platforms to expose certain companies and ameliorate the standards of services. Instead of waiting on hold to make a complaint, a woman had provided a detailed account on Facebook of her conversation with a waiter at a café, where she was explaining to him that minimum charge is an illegal practice and he can’t really force her to pay it. She shared what she felt was a success story on a group titled ‘Don’t shop here-a list of untrustworthy shops in Egypt’, a public Facebook group where middle-class Egyptians would share stories about bad consumer experiences. The group now serves as an eclectic archive for a wide range of stories recounting bad experiences (from raw chicken at a famous restaurant to slow internet to undelivered customer service promises).

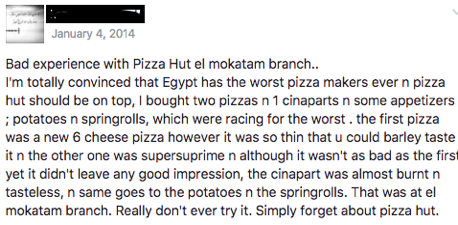

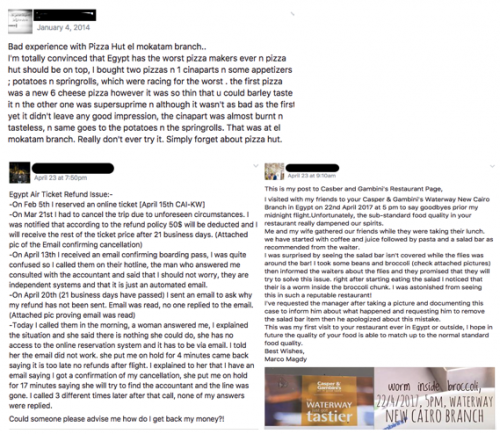

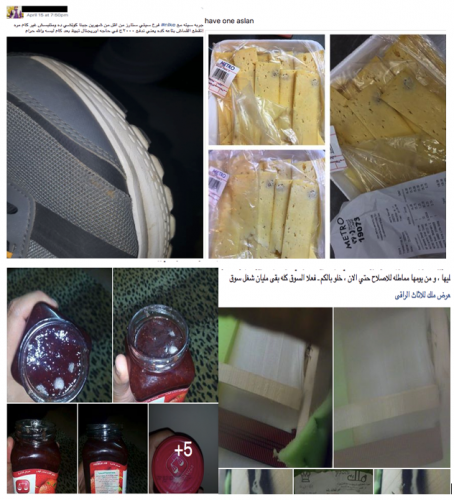

I was first introduced to the phenomenon of consumer stories on Facebook last year. As someone from a middle-class background, I’d seen friends and co-workers discussing, sharing and parodying those stories, which later on became an anticipated series on my timeline. I would look forward to reading about the little anecdotes that unveil people’s feelings of anger, distress and disgust towards the things they’d bought. Making use of the material economy of the Facebook post, members would tag businesses, upload pictures and edit their stories to include updates that bring forth an element of resolution to the problems they were posing. Unlike reviews which are usually brief in nature, the stories told on the group include vividly detailed accounts that enable a reliving of encounters and are laced with emotional arcs. It is in these rich descriptions that a Facebook post goes from mere complaining to painting a portrait of class identity. These online performances, while having much to do with the storytellers and the craft of sharing, are enacted through and vis-à-vis other actors and characters. The stories are brought to readers by the disposable objects that are presented as evidence and by embodied others that are being produced through narratives—the waiter, the shop employee, customer service representative, the voice on the phone.

Shared experiences, shared anxieties

“Had a bad shopping experience in Egypt? Feel completely lost and with no support. Share your experience with us here!”

Soon after its conception, the Facebook group had formed what Britney Summit-Gil refers to as ‘textual community’. This online community developed its own rules and aesthetics for crafting consumer stories; which include writing as much detail as possible, naming the shop and updating the group with any new information about interactions with customer service. We see through this group a collective drafting of what it means to be a ‘woke consumer’, a context where people reflexively dwell over their status as consumers and refuse being duped in everyday purchases. While people on the group seek to engage their readers in different ways, the most prominent styles used to set the scene include a chronological timeline of events, descriptive narratives of sensory experiences and a dialogue between the storyteller and a person from customer service representatives. Some members bolster their narratives by taking screenshots of textual interactions as well as through presenting documents such as receipts and contracts.

Scrolling through the stories, we could see how this textual community exhibits what the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu called “taste formations”, where taste is subject to collective constructions rather than being inherent. In these group members’ hands “taste becomes a social weapon” in demarcating between the good and the bad, the legitimate and illegitimate when it comes to the wide range of stuff consumed. These demarcations shed light on shared anxieties about transgressive products and services and on the circulation of emotions such as disgust on timelines.

In her book The Cultural Politics of Emotion, feminist scholar Sara Ahmed asks how we can tell the story of feelings “in a way that works with the complicated relations between bodies, objects and others?” Bringing Ahmed in conversation with Bourdieu leads us to consider how distinctions of taste and constructions of classed identities and communities are enacted through the work of feelings. What is shared in this Facebook group and ones like it are stories of feelings; feelings that “do things”, as Ahmed suggests, as they are not just reactions. They demarcate between objects, separate bodies and create subjectivities online.

Embodied others and classist fears

Classed identities are shaped vis-à-vis other bodies that figure throughout the stories. In many narratives told on the group, the waiter, the customer service representative, the employee at the shop, all become abstractions that are produced by fears the storytellers have about ‘being cheated’ or ‘not being respected’—which in turn are reproduced through repetition and circulation. These fears are illustrated in a parallel ad [in Arabic] for a taxi service company titled ‘did someone take advantage of you before?’, which maps out a succession of different characters often from a lower class background that try to extract money from the well-off middle-class Egyptian on a day-to-day basis—whether it were the waiter that doesn’t give back change or the man working at a kiosk that gives gum instead of change.

These stories strip away any human backstory of workers, reducing them to the role they play in unsatisfactory consumer experiences. They are as unidimensional as a faulty gas pump or a dirty table cloth. Thus, underlying the cultural logics of consumer protection, is a protection from imagined others that emphasize the fragility of consumer selves. Going back to the stories, it is important that we also look at them as instruments of power. In a sense, they are not only affective productions of abstract subjects but the unfolding negotiations that a story sparks between a customer and a manager could result in someone losing their job. Often to not compromise the reputation of their brand, many restaurants have fired employees, whose bodies have absorbed the complaints made by customers. After all, it is easier to advocate for someone getting fired if they are reduced to a faulty part in a consumer machine and not regarded as a full human that might be overworked and therefore impolite or error-prone.

Things that have gone bad

The complicated relationships between bodies, others and objects that shape the stories could be taken further by examining the photographic display of stuff that was deemed disposable and distasteful. While literature on mediated consumption has mostly focused on the lavish and the glamorous (e.g. studies of teens flaunting garments and sport shoes on social media), little has been written on mediation of trash. As Michael Thompson shows in his book Rubbish Theory, rubbish is undertheorized, as often “anthropologists interest themselves in what is noticed, treasured, and admired […] rather than with what is disregarded, discarded, and despised.” Online consumer stories are stories about ordinary stuff that went wrong. They reflect the social lives of trash, as they enable us to follow the trajectories of disposable stuff—which is taken back to businesses, exchanged, restored or residing in the chronicles of a Facebook group awaiting to resurface on people’s timelines. Moreover, the importance of documenting disposable stuff for narrative evidence grants trash an aesthetic functionality. While these things have failed to conform to commonly agreed upon standards of consumability, they play an important role in substantiating complaints. Consumer narratives are therefore assemblages of both human and nonhuman actors.

Class and dynamics of chill and care online

On another note, the debates surrounding those stories tell us something about the contested nature of the performativity of identity online. The sincerity of accounts, focus on details and the intensity of shared sentiments discussed above were subject to mockery by some people, who started turning these stories into a meme. Mimicking the descriptive styles adopted and the cataloging of actions in a comical fashion, these memes serve as intentionally imperfect repetitions that disturb the seriousness of the accounts.

The parody story typically entails a similar trajectory, as the storyteller imagines a fictional situation and proceeds with giving as much detail as possible in a sense that dramatizes the whole thing. The reader at first is led to think this to be another story reflecting frustrations about stuff or services, but soon finds out that these anxieties are put to question. What figures in stories as dilemmas is rendered to micro-annoyances through clever distortions. In a way, these memes advance a sort of moral ‘chill’ that Alana Massey describes as “being far removed from anything that looks like intensity” when it comes to consumption habits. Documenting bad experiences is seen by these memesters as “too bougie”. Caring too much and not caring that much become intersecting discourses that shape the performativity of classed identities online. Consumer stories become sites that reflect the overlapping and intermeshing of different ways of being and becoming middle class.

Consumer online storytelling tells us about circulating affects, frustrations, community-making, othering processes, ordinary stuff and creative articulations. These stories are complex networks that put different people and objects in conversation. Taking these creative instances seriously is important if we want to understand everyday dynamics of class online. However, we also need to be aware of the politics of these stories and the kind of subjects that are being created through these narratives.

Eman Shahata is an MA student of Anthropology at Goldsmiths University of London. She is currently researching secondhand cultures in Cairo.