I sort of wish this thing could be longer. But I also think maybe it shouldn’t be. I’ve spent a great deal of the last two weeks watching the world scroll by on my Twitter feed and weighing the relative merits of saying things against not saying things, but mostly I’ve just been watching, because what else can you really do? A lot of us can and do do a great deal more, but a lot of us just seem to be watching. And retweeting. The amplification of voices is, I believe, a worthwhile thing in itself.

As is always the case in situations of fast-moving catastrophe – human-caused or otherwise – emotion is hopelessly intertwined with the sharing of information, yet when it come to academic discussions of how events are covered via social media I so often see emotion ignored. Its existence is recognized, but also treated as mostly incidental. And how can this be? The emotion is overwhelming, physically so. Despair, grief, rage, a grim kind of hope. I’ve seen tweets expressing dread for the coming multitude of thinkpieces regarding white feelings about watching violence dealt out to black and brown bodies, so I don’t want to make this about what I feel but about the feelings that are there, that are real and legitimate and need to be recognized.

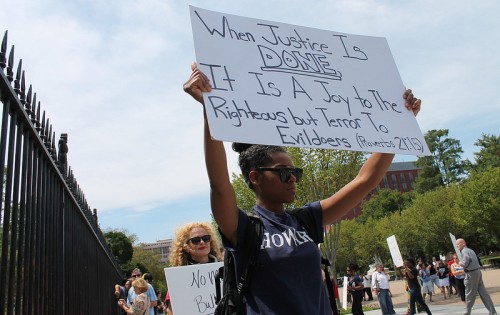

The devaluation of certain people’s emotions in favor of the emotions of others is a central feature of systems of domination and oppression. The silencing of those emotions always results. To be able to feel and to have people care about those feelings is a mark of privilege. So white people are distressed by black anger, and the hurt feelings of white people dominate the narrative. As Brittney Cooper writes in her piece “In Defense of Black Rage”:

Nothing makes white people more uncomfortable than black anger. But nothing is more threatening to black people on a systemic level than white anger. It won’t show up in mass killings. It will show up in overpolicing, mass incarceration, the gutting of the social safety net, and the occasional dead black kid. Of late, though, these killings have been far more than occasional. We should sit up and pay attention to where this trail of black bodies leads us. They are a compass pointing us to a raging fire just beneath the surface of our national consciousness. We feel it. We hear it. Our nostrils flare with the smell of it.

The delegitimization and erasure of emotion is about domination and oppression, and it’s also about the validity of sites for the expression of emotion. Recently a piece on Andrew Sullivan’s Daily Dish referenced Nathan Jurgenson’s essay on the “IRL Fetish”; it said nothing new and got almost everything wrong, but it made me think about emotion and disconnection, and what it means to disconnect.

Over and over in the last few days I’ve seen people of color on my Twitter timeline say (paraphrasing) “I can’t take this anymore, I need to step away. I can’t watch. This is too painful.”

Why don’t we talk about this when we talk about voluntary disconnection?

The stories are seemingly always about and told by people who have the privilege of choosing to step away, to log off, to unplug. People who may “depend” on social media and digital communication for work, to maintain basic everyday connections with friends and family, to simply entertain themselves. And we do write about the cost of opting out, and we also write about how “opting out” isn’t actually possible. But we don’t talk much about how people denied power are locked into the act of witness, subject to massive psychological pain with each fragment of news that scrolls by, every image, every Vine, every livestream clip. How simply being there and watching feels like an imperative, like something necessary, but also amounts to a barrage of emotional assault. And when we talk about how one can’t opt out, we need to talk about how what we see on timelines and hashtags is something that marginalized and oppressed people can’t step away from. It’s still there.

If you’re lucky, you can walk away from Twitter and close your eyes and, for a while, not see. But for a person of color, it’s still there, all around, and it couldn’t possibly be any more real. I’m white. I can step away, and suddenly it’s at a distance and I can breathe again. That’s my privilege. The act of disconnection means something different for me, and is embedded within different arrangements of power and inequality. And if I want to talk about my significantly lesser pain, most people will at least probably listen, while for the majority of white America, black anger and despair mediated by all forms of communication amount to shouting in a dark, closed room.

I’m getting very, very bored with discussions about how much more fulfilled we are if we stop checking Twitter.

That’s not real life.

Sarah is on Twitter – @dynamicsymmetry

Comments 2

#FergusonSyllabus: Resources for Discussing Ferguson in the Classroom | ACADÆMONIUM — August 22, 2014

[…] from Twitter and other social media can be a teachable moment, as argued in this piece on disconnection as privilege. I’m sure we have all seen friends make attempts to shut down conversation of current events […]

Atomic Geography — August 24, 2014

Sarah, one of your best. Congrats. Atomic