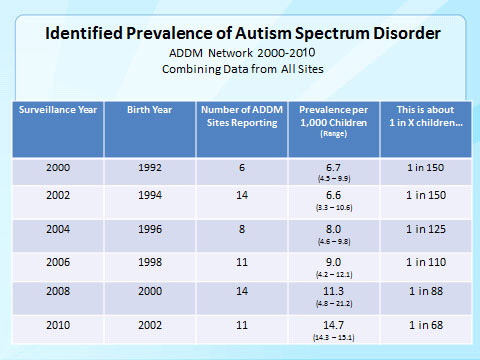

Several months ago, the CDC released a report on Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD). They found that as of 2010, 1 in every 68 U.S. children are on the ASD spectrum. This is up from 1 in every 150 children just ten years prior. This means that rates have more than doubled. The reasons for the large increase are fodder for some wonderfully interesting conversations and heated debates about biology vs. environment vs. culture vs. the Medical Industrial Complex. Putting these debates aside for another day, however, I instead want to talk about how new technologies can serve this ever growing population. As a quick caveat, I should say that I am a person who dabbles in disability studies research. My hope is that those who know more than I—through personal experience and/or professional expertise—will add nuance to the ideas I present below and help guide the discussion into all of the complex places I know it can go, but don’t quite know how to take it.

According to the latest Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) (released in May 2013) Autism Spectrum Disorders are those that negatively affect social-emotional responses and communication skills across contexts, inhibit relationship building and development, and manifest behaviorally through inflexibility, inappropriate responses to stimulation, and obsessive focus on narrow topics. I encourage you to check out the link above for the full diagnostic criteria.

The first thing to notice about Autism’s official description is the incredibly ableist language in which the DSM-V authors wrote. If you click the link above, you will see a lot of words like “deficit,” “symptoms,” and “severity.” Reframing this for the purposes of the this blog post, we can instead understand Autism as a way of engaging the world that is poorly accommodated by interpersonal social structures (i.e., norms of interaction) and institutions (e.g., schools). The degree of difference between a person with an Autistic sensibility and those termed “Neurotypical” represents a person’s location upon the Autism spectrum, and the ease or difficulty with which they can function in an environment built for Neurotypicals.

Understanding Autism as a poorly accommodated way of being in the world, it is important to look at the means by which those with ASD can improve upon their plight. One way, I argue, is through the written mode of communication afforded by Internet technologies.

Jason Rodriquez wrote a fantastic article about the use of Internet forums by people with early-onset Alzheimer’s. Although Rodriquez focused on the construction of identity narratives, his data touched on an interesting point that I explore further here. Some of the participants on the forum Rodriquez studied expressed relief at the opportunity to engage in meaningful communication, avoiding the limitations of traditional interaction. In particular, these people with varying degrees of dementia, found it difficult to keep up with the fast-paced, asynchronous, social-cue-laden, distracting environment of face-to-face communication. The forums allowed them to pause, think, process, and articulate in ways that they otherwise could not. This is a big deal. It gave these participants an outlet to connect on a human level that was otherwise denied. Moreover, participants reported clinical benefits from continued engagement, as they exercised their brains in an accommodating environment. That is, for people with early-onset Alzheimer’s, the forum provided reprieve from a “disabling” condition.

Extending this, I wonder about the extent to which digital mediation can be used as an accommodation for those with ASD in general, and those with intellectual disabilities more generally. The key problem for people with ASD is a difficulty fitting themselves into social situations. But what if social situations are such that the differences between those with ASD and Neurotypicals are made less consequential and therefore less disabling? Digitally mediated forms of sociality, I argue, can potentially create such an environment.

The key factors are written—rather than spoken—communication, asynchronicity, and expansive niche groups.

If it is difficult for a person to read or demonstrate social cues through facial expression and body language, than writing and reading may be an easier and more effective means of communication than spoken or face-to-face interaction. Such text based communication is widely prevalent through social media, SMS, and community forums.

Of course, people can (and do) write in implicit, sarcastic, and polysemic ways. This brings me to my second point: asynchronicity. Digitally mediated communication often (though not always) includes a pause. This pause is hugely useful for communication between people using slightly different languages or logics. It seems that when someone with ASD can take the time to read, think about, and respond to others’ communications, the likelihood of mutual understanding will increase.

Finally, these communicative advantages can be put to use in the expansive niche communities available online. In addition to social issues, some people with ASD express an intense interest and focus on particular topics. Although this focus may seem abnormal in many settings, it likely fits quite comfortably within communities centered around the topic. For instance, if someone thinks and talks a lot about fishing, this might create distance between them and co-workers or classmates, but the other members on TheBigFishTackle.com will remain fascinated and continue to provide stimulating conversation.

Importantly, this is not to say that The Internet solves all problems of ableism. On the contrary, most digital social technologies are built with Nuerotypicals in mind, and this could have dire consequences for “Other” populations. For instance, the staying power of content online means that social faux-pas have a longer—sometimes permanent—shelf life, and can come back in ways that tangibly harm those who commit them. Further, I certainly do not mean to imply that people with ASD should lock themselves away behind closed doors, lit only by the glow of a computer screen. Rather, I contend that in a disabling world, some digital social technologies may be unexpected, unintentional, means of accommodation. Moreover, sociality begets sociality, and if those with ASD have an opportunity to engage socially in ways that are comfortable for them, they can be more fully integrated members of society, while Neurotypicals can learn to better interact with those who deviate from their normative social expectations.

Most importantly, however, it’s time for researchers to examine how people with intellectual disabilities experience a technologically changing world. This post is an early, largely speculative and open, attempt in this direction.

Thoughts and critiques welcome. Let’s push this conversation forward.

Follow Jenny on Twitter @Jenny_L_Davis

Pics Via:

http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html (chart)

http://biblioteca.uam.es/psicologia/exposiciones/ (Ribbon)

Comments 1

ArtSmart Consult — June 11, 2014

All good points Jenny. Autism is a gift that is ideal for an online society.

http://thegiftsofautism.com/

Unfortunately, society insists on forcing square pegs through round holes of tradition. In this case, the round holes are what Rich Gold refers to as "wet space."

http://ic-pod.typepad.com/design_at_the_edge/2007/05/fire_juggling_o.html

The sharp corners (gifts) get shaved away, while traditionalists congratulate themselves for having helped the autistic adjust to a traditional society.