Over at the CUNY Digital Labor Working Group Blog, I’ve been participating in a symposium on Angela Mitropoulos’s book Contract and Contagion. I think there are a lot of conversations and ideas that will be of interest to Cyborgology readers, so I want to highlight a few of these and encourage you to visit the DLWG blog and participate in the conversation yourself.

Anne Boyer discusses the politics of how we arrange ourselves:

Indeed, “how to arrange” ourselves and our infrastructure is the question forced back at us at every turn by this minute of history: it is as much a question posed by the blockade or the riot as it is the occupation, it is as much a question posed by the struggle in the home or for a home as it is in the struggle in the workplace and the streets. It is there when we are sick and there is no one to care for us or our people are sick and we are not there to care for them or when we have no people at all; it is there in the ports and shipping hubs; it is there in our digitized labors and the industrial and reproductive labors that support them; it is there in the leveler of an unstable climate that increasingly turns even what we might think of the polis into an urgent site of necessary care and renders the oikos as shelter for no one.

To be a bit reductive, Boyer is arguing that politics (either reactionary or revolutionary) isn’t so much in what we do as it is in the institutions or arrangements in and through which we work. A “leaky” arrangement, to use Boyer’s term, is one that allows resources (time, energy, attention, material support) to be siphoned or diverted from the channels that reproduce and maintain current arrangements. Perhaps leaky arrangements bend circuits (of capital, of care, of time, of money, of social reproduction) so they create what Atari Teenage Riot has called “riot sounds”? I ask this last question both because my contribution to the forum is about sound, but also because I think ATR’s concept of “riot” is different than the traditional, political concept of riot and more like the “leaky” riot that Boyer discusses. You can read more about how I understand ATR’s notion of “riot sounds” here. This sort of circuit bending echoes what Constantina Zavitsanos calls “looking at a thing side-eyed or periscopically”: how do we bend the frequencies so they do different things, emphasize different angles, shift figure/ground relationships? I need to think more about this relationship between leaky rearrangements and riot sounds.

But, for Cyborgology readers, Boyer’s piece opens up questions such as: How are algorithms ways of arranging ourselves? Patricia Clough also opens up this question in her post, where she argues “they are real objects, spatiotemporal data structures.” How might we make algorithms “leaky,” especially because algorithms can adapt to compensate for leaks? Or, as Clough also suggests, algorithms are already “leaky,” but that leakiness is obscured in various ways.[1] Basically (and I may be oversimplifying here), algorithms can appear to reduce everything neatly to quantifiable terms because the terrain in, on, and through which they operate is already smoothed out in very particular ways, so that some messy reductions seem neat and clean instead. For example, patriarchy and white supremacy might make an inadequate quantification seem adequate–standardized test scores can pass as adequate measurements of scholastic aptitude or teacher performance because white supremacy and classism covers over the racialized socioeconomic conditions that affect student performance. So the leaks are there. How do we bend the algorithms or the circuits of social reproduction so that the leaks, well, leak in ways that water our roots? How do we make riot sounds of our own, sounds that are immoderate in ways that make the lives of us “women and slaves” more survivable?

Aren Aizura talks about

little data. For instance, parental surveillance: the time of the preteen fighting to have the “independence” of an iPhone is long gone. These days parents totally want their kids wired up. Give your kid an iPhone and you can sync her messages to download into your phone: incoherent emojis, texts from boyfriend/girlfriend and all. Want to know where your daughter is? Just bring up the app and you can see her GPS signal pulsing on the map, still or moving. This is not 1984, you understand. It’s just parents keeping track.

Little data, then, takes the tools of big data and applies them not to populations (which is what big data does), but to individuals–your kid, for example, or even yourself (e.g., the Quantified Self movement, which Aizura discusses). Aizura uses little data to highlight the ways that contemporary contracts (as practices, as institutions) maintain the same old inequalities with fancier, newer, more efficient tools and methods. For example, little data updates a longstanding tradition of devaluing so-called women’s work when it is performed by women in the home, but valuing it when it is appropriated by men and performed in a publicly visible forum (think about the different status of home cooks, who are generally women, and chefs, who are l

argely men). Aizura’s discussion of the role of the QS phenomenon in the ongoing devaluation of feminized care labor resonates with my earlier post on feminization and hyperemployment. Aizura’s post suggests that quantifiability does the work of gendered (de)valuation of care work: “Nurses in the global north are trained precisely to perform impersonal data collection; by contrast, South East Asian health tourism markets depend on South East Asian care workers being understood to “care more” about patients, elderly people, children, and to expect less remuneration.” Care that can be profitably quantified is “masculinized” (i.e., incorporated into the wage-labor economy), whereas unprofitably quantifiable or just unquantifiable care is “feminized” (i.e., excluded from the ‘real’ economy).

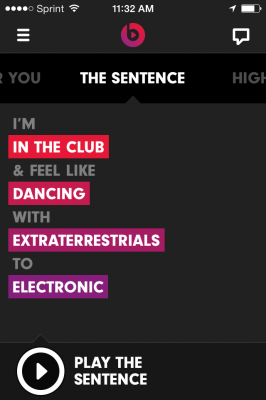

I wonder if affect is how we perceive and pay attention to non-quantified care, which Aizura suggests is also “a kind of attention.” If affect is an easy way to access non-quantified care, it seems to me, at least, that it’s also an easy way to render this non-quantified care quantifiable. For example, beats music, which I think is fabulous as a music streaming platform, will craft a radio station for you based on how you feel. Called “The Sentence,” this feature asks you to fill in the variables in the following sentence: “I’m X feeling like Y with Z to ABC.” This is just one easy example of how we’re turning affect into data. And I don’t think the answer is to find affects that aren’t quantifiable, but to think about ways of making data and quantification itself “leaky,” to use Boyer’s term. How would you use this beats interface to make “riot sounds” in its algorithms?

[1] Clough writes: “Quantities rather are conditioned by their own indeterminacies since algorithmic architectures are inseparable from incomputable data or incompressible information—that information or liveliness between zeros and ones.”

Robin is on Twitter as @doctaj.

Comments 1

ArtSmart Consult — March 28, 2014

Make algorithms decentralized and inclusive.