Once, many years ago, a friend and I Got Into It via a series of Livejournal comments.

Yes, you already know that this is going somewhere good.

I’ve long since forgotten what the It was about, though it was probably something exactly as silly as you’d expect. I don’t remember how it resolved itself; that friend and I are not friends anymore and haven’t spoken in nearly a decade, so I can’t ask them without things getting weird. What I do remember was one thing this friend said, which I’ve remembered as long as I have because it might be one of the single most ridiculous things anyone has ever said to me in any setting: I mentioned that I didn’t like their tone, and they responded, “there is no tone on the internet.”

I’m pretty sure I never engaged with that statement directly, because I had no idea how to do so. On the one hand, of course there’s tone on the internet, as anyone who’s ever used the internet for more than about ten minutes should know. On the other hand, I had the vague feeling that they had some kind of valid point under the ridiculousness of the statement, though I had no idea how to articulate it to myself.

So getting away from trash-talking years and years after the fact, how do we talk about “tone” mediated by digital communication?

One way in which tone in this setting operates is obviously via the basic written word, which did not begin with AIM and email and LJ comments, nor of course would it ever end there. This is one reason why what they said made me go “wait, what?” Tone has been conveyed through writing since the beginning of time, as my students often regrettably write. See what I just did? There was some gentle scorn in that sentence (there has been some gentle scorn in the picture since I started writing this) and if I’m a good writer and my reader is sensitive to the cues of this kind of writing, that tone will get picked up and properly interpreted. Tone is carried in prose in all kinds of ways that don’t involve saying I AM FEELING THUSLY, and the system of organization of words and flow and connotation can get extremely rich and complex in ways that don’t involve voice or facial expression, and in fact allow for kinds of tone that wouldn’t be possible in a face-to-face setting. Like most writing, it’s a skill, and some of our historical figures most known for their acidic wit have been extremely skilled in this respect. Given that it’s a skill, though, there are a lot of ways in which to get it wrong. This naturally leaves written communication open to misinterpretation.

So none of this is unique to the comment thread in which my friend and I were engaged. It’s been a feature of human communication since we started writing notes to each other, and indeed since we started verbally communicating at all. There is tone on the internet because there is tone in every other facet of linguistic communication, whether or not it involves physical co-presence.

However, I do think my friend had a point in that even conventional written communication mediated by digital technology gets a bit more complicated than a letter.

Yesterday, in her post on the communicative limitations of the telephone, Jenny Davis noted that a successful conversation requires a natural rhythm that, if disrupted, creates problems:

Ethnomethodologists and conversation analysts say that the best conversations have a continuous flow, with each speaker picking up just as hir partner leaves off, barely overlapping. This kind of conversation requires intense engagement, and highly accurate cue-reading on the parts of interaction partners. Interruptions and extended silences disrupt the conversational flow, and create a less satisfying interaction.

She goes on to mention that communication like posts in a thread, which count as “asynchronous” communication, do away with some of the difficulties in maintaining the smooth flow of a conversation. However, those difficulties don’t entirely disappear, because of the temporal connotations that can exist between two or more people in a close-knit group who have, between them, constructed their own little complex system of tonal cues. A comment in a Livejournal thread might be asynchronous, waiting for me to answer it in my own good time, but if my friend can see or at least infer that I’m currently immediately present online – either because I usually respond quickly or because they can see me on their AIM buddy list – and I don’t respond for a while, that in itself might carry tonal connotations. It also might not, but either way its ambiguity leaves it open to the possibility of some major misinterpretation (in linguistics this use of time as a form of nonverbal communication is known as Chronemics, and can be used to express and maintain a variety of things, from intimacy to differential power relations).

Jenny points out that the telephone, because it removes all conversational social cues but voice, constrains the range of information available to the participants. Essentially, it narrows the band – the types and amount of information are reduced, and people are operating with less and more incomplete data than usual.

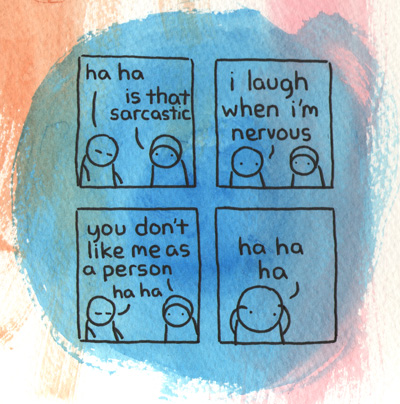

I argue that communication over the web and via other forms of digital technology are both more and less constrained than face-to-face communication. On the one hand, unless you’re using something like FaceTime or Skype (which I’m purposefully not addressing here), you don’t have access to any visual body-language data about what someone is feeling or possibly thinking, and you probably aren’t hearing their voice. You’re often just typing back and forth, and in that – like a letter – you don’t have the same or as many conversational tools available to you. On the other hand, because of the incredible flexibility, diversity, and creativity inherent in digital communication, you have many more tools available, and the toolbox is receiving new additions all the time. We can communicate via the time it takes to respond – I can’t be bothered with this right now, or I’m upset enough that I need to go away, or just I am passive–aggressively ignoring you – but also through emoticons, gifs, countless numbers of memes, “poor” spelling and grammar, and any number of other things that may be internets-wide or just existent within small social groups.

The problem with this wildly flexible, emergent creativity is that it can be difficult to get everyone on the same page about what these cues mean and how one should use them properly. While there are often generally accepted patterns of use, those patterns are subject to rapid change as people appropriate symbols and techniques of using them for their own specific needs. This obviously happens in any form of human communication, but this stuff is all new enough that we’re still figuring out how it works and how it can work. Again, this creates potential for disagreement and misinterpretation that doesn’t exist in the same way in physically co-present communication, or even on a telephone.

So yes, there is tone on the internet, friend-in-the-past. We just don’t always agree on what that tone is.

I still don’t like yours, by the way.

Sarah maintains a vaguely irritated tone regarding everything on Twitter – @dynamicsymmetry

Comments 3

Gaelan — January 20, 2014

Hi! Love the article. Still digesting it.

Question, though. Where is the leading picture from? Is there a place I can look to find out?

Friday Roundup: Jan. 17, 2014 » The Editors' Desk — January 22, 2014

[…] When healthcare-dot-gov took on a life of its own, why we don’t like talking on the phone, the complexity of tone in digital communication, and how resilience is work […]