Last week I wrote a piece on the increasing prevalence of the Bokeh blur effect – and other filmic effects – in forms of visual media where we once saw them rarely if at all. Nathan Jurgenson then followed up with a response that articulated some interesting and important questions that this trend raises – which I want to consider further here, though please don’t mistake this as anything other than additional groping toward something that still needs a lot of working-through.

I tend to tie most things I blog about back to storytelling in some way – it’s just how I roll – and in my original piece I did this fairly explicitly. How we document things is ultimately about how we tell stories – and the important thing to bear in mind here is that any story told by someone else is necessarily going to be mediated by that person, regardless of whether or not it’s technically factual or fictional. Every account is filtered through someone else’s perceptions, assumptions and understandings. When events are documented on video, that documentation is still subject to what the person filming chose to focus on and what they ignored, what they saw and what they weren’t present for, and – in the case of Bokeh – the technology they used.

What sets effects like Bokeh apart is, as I said, the visual-textual cues that they make up for us, which are some of the ways we know – or used to know – that we’re watching a documentary or news footage as opposed to a dramatic film. But with Bokeh becoming more common in footage that we’re used to viewing and interpreting as “factual” – with footage of supposedly real events looking more and more filmic – we have to consider the possibility that this encourages us to understand current events as other than current, and even other than “events” in the sense that we’ve used the term. Nathan suggests that filmic effects impose a sense of order and coherence on an otherwise confusing present; by framing messy, uncomfortable stories within more traditional narratives we can impose on them the comforting good/evil/right/wrong trappings of those narratives. In effect, the implication is that technology may be allowing us to mythologize our present.

This is actually an echo of other discussions we’ve had here before, perhaps most famously in Nathan’s essay on the faux-vintage photo but continued in an examination of what instagram means when applied to photos taken in present-day war zones, as well as HDR effects applied to photographs of ruined spaces. What’s common in all of these is an apparent desire – not caused by technology but certainly enabled by it – to view our messy present as a gauzy, comforting, over-romanticized past. Anything for which we can feel nostalgia must necessarily be not only more pleasant but also more meaningful; applying these effects to visual media therefore allows us to imbue with meaning and authenticity the very stuff that we fear is neither meaningful or authentic.

What happens when we make a document of current reality into a glossy fiction? Instagram is making a claim on age, albeit it an overtly artificial one, but what about Bokeh? In order to answer that, I think it’s useful to understand what stories are, at all times and in all places: in a subtle way, we understand all stories to be about events that have already taken place, regardless of what tense the story is told in. And often those stories are one step removed, told by a faceless and often omniscient narrator who may or may not be at all involved in the action. It’s no accident that the traditional baseline for fiction – at least in English – is second-person past-tense.

Telling stories has been used as a technique to rouse rabbles, to teach new generations, and to make it clear who we are and where we come from. Storytelling is unquestionably powerful. But by simplifying and subtly removing us from events with which we aren’t necessarily involved and over which we have no control, it also has the potential to let us off the hook. Done right, it requires less from us than something that we perceive in all its messy reality. See: the distress that civil rights activists express at the de-radicalization of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Making our present or very-near-past into a fictionalized distant past also has another effect that’s been covered here: it atemporalizes both our memory and our lived experience. By experiencing the present as a fictionalized past – or by, in Nathan’s words, “view[ing] our present as always a potential documented past” – we collapse the categories of past and present. By viewing a romanticized, glossy picture of a ruined space and extending our imagining of ruin and death into the present and the future, we collapse those categories as well. Atemporality isn’t just about technology – it’s about what our technology allows us to do to our stories.

Atemporality is also – if one uses Bruce Sterling’s characterization, and I do – about multiplicity, about an abundance of different nonlinear avenues to information that is equally illuminating and confusing. There’s been a tremendous amount of writing on how the internet helps more voices to be heard (though often with ominous caveats about the signal-to-noise ratio). Digital technology – how we share, record, process, mediate, and store information – helps us to tell and to be told more and more stories from more and more people.

They were all always stories. We have all always been storytellers. But now we are louder, faster, more polished, both sharper and more pleasingly blurry, at once bursting with meaning and uncomfortably meaningless. The idea that everything is fundamentally a story has been around for a long time – and the boundaries between fact and fiction have always been porous – but at least the different tellers were easier to parse. Now we’re all at once poets and scribes – and we’re also time-travelers, not moving along a stationary linear timeline but pulling all of our experience of time into ourselves like temporal black holes.

Perhaps most ironic is what – according to Nathan – all of this mythologizing, glossy present nostalgia, and grasping for the present is actually a reaction to: Our increasing messy and confusing Now, with its lack of certainties, knowabilities, and clear distinctions between categories.

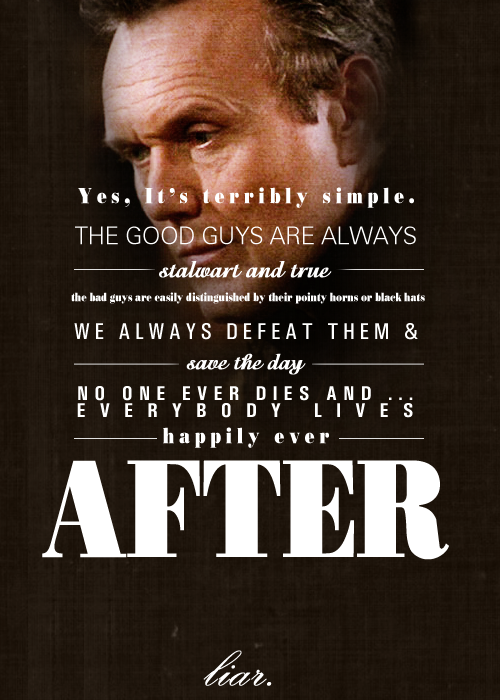

We want everything to have a Once Upon a Time. We want to make the world a fairy tale because we all understand fairy tales; we know that witches and dragons are always wicked and princes and princesses are always brave and beautiful and good; we know that even if the princess pricks her finger on the spinning wheel’s spindle, she isn’t really dead and the prince will awaken her. We know that good will win out and evil will be clearly identifiable. If we know how the story begins, we immediately know how it ends, and it always ends Happily Ever After.

But there isn’t just one story. There isn’t just one form of documentary technology, one kind of mediation, one set of immediately identifiable textual cues – and what we have keep shifting their meaning, as news begins to look more filmic and fantasy films begin to look more like “reality”. Our technologically-mediated storytelling is every bit as world-destroying as it is world-creating; if it appears to clarify some categories it collapses many others. The very thing we look to in order to provide a little simplicity may only everything endlessly more confusing in the end.

Comments 4

Digital Poets, Scribes, & Time-travelers | Story and Narrative | Scoop.it — September 4, 2012

[...] I tend to tie most things I blog about back to storytelling in some way – it’s just how I roll – and in my original piece I did this fairly explicitly. How we document things is ultimately about how we tell stories – and the important thing to bear in mind here is that any story told by someone else is necessarily going to be mediated by that person, regardless of whether or not it’s technically factual or fictional. Every account is filtered through someone else’s perceptions, assumptions and understandings. When events are documented on video, that documentation is still subject to what the person filming chose to focus on and what they ignored, what they saw and what they weren’t present for, and - in the case of Bokeh – the technology they used. [...]

Digital Poets, Scribes, & Time-travelers » Cyborgology | Transliteracy: Physical, Augmented, & Virtual Worlds | Scoop.it — September 6, 2012

[...] [...]

In Their Words » Cyborgology — September 9, 2012

[...] “technologically-mediated storytelling is every bit as world-destroying as it is world-creating” [...]

No One Tells Stories Alone » Cyborgology — September 15, 2012

[...] on with regards to ICTs – especially social media technologies – and storytelling. My post last week dealt with how the atemporal effects of social media may be changing our own narratives and how [...]