Last month at TtW2012, a panel titled “Logging off and Disconnection” considered how and why some people choose to restrict (or even terminate) their participation in digital social life—and in doing so raised the question, is it truly possible to log off? Taken together, the four talks by Jenny Davis (@Jup83), Jessica Roberts, Laura Portwood-Stacer (@lportwoodstacer), and Jessica Vitak (@jvitak) suggested that, while most people express some degree of ambivalence about social media and other digital social technologies, the majority of digital social technology users find the burdens and anxieties of participating in digital social life to be vastly preferable to the burdens and anxieties that accompany not participating. The implied answer is therefore NO: though whether to use social media and digital social technologies remains a choice (in theory), the choice not to use these technologies is no longer a practicable option for number of people.

In the three-part essay to follow, I first extend this argument by considering that it may be technically impossible for anyone, even social media rejecters and abstainers, to disconnect completely from social media and other digital social technologies (to which I will refer throughout simply as ‘digital social technologies’). Even if we choose not to connect directly to digital social technologies, we remain connected to them through our ‘conventional’ or ‘analogue’ social networks. Consequently, decisions about our presence and participation in digital social life are made not only by us, but also by an expanding network of others. In the second section, I examine two prevailing discourses of privacy, and explore the ways in which each fails to account for the contingencies of life in augmented realities. Though these discourses are in some ways diametrically opposed, each serves to reinforce not only radical individualist framings of privacy, but also existing inequalities and norms of visibility. In the final section, I argue that current notions of both “privacy” and “choice” need to be reconceptualized in ways that adequately take into account the increasing digital augmentation of everyday life. We need to see privacy both as a collective condition and as a collective responsibility, something that must be honored and respected as much as guarded and protected.

Part I: Distributed Agency and the Myth of Autonomy

For the skeptical reader in particular, I want to begin by highlighting that the effects of neither participation nor non-participation in digital sociality are uniform or determined, and that both are likely to vary considerably across different social positions and contexts. An illustrative (if somewhat extreme) example is the elderly: Alexandra Samuels caricatures the absurdity of fretting over seniors who refuse online engagement, and my own socially active but offline-only grandmother makes a great case study in successful living without digital social technology. Though 84 years old, my grandmother is healthy and can get around independently; she lives in a seniors-only community of a few thousand adults (nearly all of whom are offline-only as well), and a number of her neighbors have become her good friends. She has several children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren who live less than an hour away, and who call and visit regularly. As a financially stable retiree, she can say with confidence that there will be no job-hunting in her future; her surviving siblings still send letters, and her adult children print out digital family photos to show her. For these reasons and others, it would be hard to make the case that either she or any one of her similarly situated friends suffers from digital deprivation.

In contrast, the “Logging Off and Disconnection” panel highlights how the picture of offline-only living shifts if some of the other factors I list above change. Whereas my grandmother has a number of friends with whom she spends time (and who, like her, do not use digital social technologies), Davis describes the isolation that digital abstainers experience when many of the friends with whom they spend time do use digital social technologies. Much to their dismay, non-participating friends of social media enthusiasts in particular can find themselves excluded from both offline and online interaction within their own social groups. Similarly, Roberts finds that even 24 hours of “logging off” can be impossible for students if their close friends, family members, or significant others expect them to be constantly (digitally) available. In these contexts, it becomes difficult to refuse digital engagement without seeming also to refuse obligations of care. Nor is what I will call abstention-related atrophy limited to relationships with friends and family members; professional relationships and even career trajectories can suffer as well. Vitak points out that, for job-seekers, the much-maligned proliferation of ‘weak ties’ that social media has been accused of fostering is a greater asset for gaining employment than is a smaller assortment of ‘strong ties.’ Modern life has become sufficiently saturated with social media to support use of what Portwood-Stacer calls its “conspicuous non-consumption” as a status marker: in the United States, where 96.7 percent of households have at least one television, “I’m not on Facebook” is the new “I don’t even own a TV.” That even a few people read the purposeful rejection of social media as a privilege signifier implicitly demonstrates the high cost of abstaining from social media.

Conversations about logging off or disconnecting have continued in the weeks since TtW2012. Most recently, PJ Rey (@pjrey) makes the case that social media is a non-optional system; because societies and technologies are always informing and affecting each other, “we can’t escape social media any more than we can escape society itself.” This means that the extent to which we can opt-out is limited; we can choose not to use Facebook, for example, but we can no longer choose to live in a world in which no one else uses Facebook (whether for planning parties or organizing protests). As does Davis, Rey argues that “conscientious objectors of the digital age” therefore risk losing social capital in a number of ways. I would like to suggest, however, that even those who are “secure enough” to quit social media and other digital social technologies can not separate from them fully, nor can so-called “Facebook virgins” remain pure abstainers. Rejecters and abstainers continue to live within the same socio-technical system as adopters and everyone else, and therefore continue to affect and to be affected by digital social technology indirectly; they also continue to leave digital traces through the actions of other people. As I elaborate below, not connecting and not being connected are two very different things; we are always connected to digital social technologies, whether we are connecting to them or not. A number of digital social technology companies capitalize on this fact, and in so doing amplify the extent to which digital agency is increasingly distributed rather than individualized.

In this section, I use Facebook as a familiar example to illustrate the near-impossibility of erasing digital traces of one’s self most generally. Many of the surveillance practices that follow here are not unique to Facebook, but the difficulty of achieving a full disengagement from Facebook can serve as an indicator of how much more difficult a full disengagement from all digital social technology would be. First, consider some of the issues that face people who actually have Facebook accounts (at minimum a username and password). Facebook has tracked its users’ web behavior even when they are logged out of Facebook; the “fixed” version of the site’s cookies still track potentially identifying information after users log out, and these same cookies are deployed whenever anyone (even a non-user) views a Facebook page. Last year, a 24-year-old law student named Max Schrems discovered that Facebook retains a wide array of user profile data that users themselves have deleted; Schrems subsequently launched 22 unique complaints, started an initiative called Europe vs. Facebook, and earned Facebook’s Ireland offices an audit.

In one particular complaint, Schrems alleges that Facebook not only retains data it should have deleted, but also builds “shadow profiles” of both users and non-users. These shadow profiles contain information that the profiled individuals themselves did not choose to share with Facebook. For a Facebook user, a shadow profile could include information about any pages she has viewed that have “Like” buttons on them, whether she has ever “Liked” anything or not. User and non-user shadow profiles alike contain what I call second-hand data, or information obtained about individuals through other individuals’ interactions with an app or website. Facebook harvests second-hand data about users’ friends, acquaintances, and associates when users synchronize their phones with Facebook, import their contact lists from other email or messaging accounts, or simply search Facebook for individual names or email addresses. In each case, Facebook acquires and curates information that pertains to individuals other than those from whom the information is obtained.

Second-hand data collection on and through Facebook is not limited to the creation of shadow profiles, however. As a recent article elaborated, Facebook’s current photo tagging system enables and encourages users to disclose a wealth of information not only about themselves, but also about the people they tag in posted photos. (Though not mentioned in the piece, the “tag suggestions” provided by Facebook’s facial recognition software have made photo tagging nearly effortless for users who post photos, while removing tags now involves a cumbersome five-click process per each tag that a pictured user wants removed.) Recall, too, that other companies collect second-hand data through Facebook each time a Facebook user authorizes a third party app; by default, the third-party app can ‘see’ everything the user who authorized it can see, on each of that user’s friends’ profiles (the same holds true for games and for websites that allow users to log-in with their Facebook accounts). Those users who dig through Facebook’s privacy settings can prevent apps from accessing some of their information by repeating the tedious, time-consuming process required to block a specific app for each and every app that any one of their Facebook ‘friends’ might have authorized (though the irritation-price of doing so clearly aims to guide users away from this sort of behavior). Certain pieces of information, however—a user’s name, profile picture, gender, network memberships, username, user id, and ‘friends’ list—remain accessible to Facebook apps, no matter what; Facebook states that this makes one’s friends’ experiences on the site (if not one’s own) “better and more social.” Users do have the ‘nuclear option’ of turning off all apps, though this action means they cannot use apps themselves; their information also still remains available for collection through their friends’ other Facebook-related activities.

Facebook representatives have denied any wrongdoing, denied the existence of shadow profiles per se, and maintained that there is nothing non-standard about the company’s data collection practices. Nonetheless, even the possibility of shadow profiles raises a complicated question about where to draw the line between information that individuals ‘choose willingly’ to share (and are therefore responsible for assuming it will end up on the Internet), and “information that accumulates simply by existing.” The difficulty of making this determination reflects not only the tensions between prevailing privacy discourses, but also the growing ruptures between the ways in which we conceptualize privacy and the increasingly augmented world in which we live.

As a headline in The Atlantic put it recently, “On Facebook, Your Privacy is Your Friends’ Privacy”—but what does that mean? How should we weigh which of our friends’ desires against which of our own? How are we to anticipate the choices our friends might make, and on whom does the responsibility fall to choose correctly? The problem is that we tend to think of privacy as a matter of individual control and concern, even though privacy—however we define it—is now (and has always been) both enhanced and eroded by networks of others. In a society that places so much emphasis on radical individualism, we are ill-prepared to grapple with the rippling and often unintended consequences that our actions can have for others; we are similarly disinclined to look beyond the level of individual actions in asking why such consequences play out in the ways that they do.

‘Simply existing’ does generate more information than it did two generations ago, in part because so many different corporations and institutions are attempting to capitalize on the potentials for targeted data collection afforded by a growing number of digital technologies. At the same time, surveillance of individual behavior for commercial purposes is nothing new, and Facebook is hardly the only company building data profiles to which the profiled individuals themselves have incomplete access (if any access at all). What is comparatively new about Facebook-style surveillance in social media is the degree to which disclosure of our personal information has become a product not only of choices we make (knowingly or unknowingly), but also of choices made by our family members, friends, acquaintances, or professional contacts. Put less eloquently: if Facebook were an STI, it would be one that you contract whenever any of your old classmates have unprotected sex. Even one’s own abstinence is no longer effective protection against catching another so-called ‘data double’ or “data self,” yet we still think about privacy and disclosure as matters of individual choice and responsibility. If your desire is to disconnect completely, the onus is on you to keep any and all information about yourself—even your name—from anyone who uses Facebook, or who might use anything like Facebook in the future.

If we dispense with digital dualism—the idea that the ‘virtual,’ ‘digital,’ or ‘online’ world is somehow separate and distinct from the ‘real,’ ‘physical,’ or ‘face to face’ world—it becomes apparent that not connecting to digital social technologies and not being connected to digital social technologies are two different things. Whether as a show of conspicuous non-consumption, an act of atonement and catharsis (as portrayed in Kelsey Brannan’s [@KelsBran] film Over & Out), or for other reasons entirely, we can choose to accept the social risks of deleting our social media profiles, dispensing with our gadgetry, and no longer connecting to others through digital means. Yet whether we feel liberated, isolated, or smugly self-satisfied in doing so, we have not exited the ‘virtual world’; we remain situated within the same augmented reality, connected to each other and to the only world available through flows that are both physical and digital. I email photographs, my mother prints them out, and my grandmother hangs them in frames on her wall; a social media refuser meets her own searchable reflection in traces of book reviews, grant awards, department listings, and RateMyProfessors.com; a nearby friend sees you check-in early at your office, and drops by to surprise you with much needed coffee. A news story is broken and researched via Twitter, circulated in a newspaper, amplified by a TV documentary, and referenced in a book that someone writes about on a blog. Whether the interface at which we connect is screen, skin, or something else, the digital and physical spaces in which we live are always already enmeshed. Ceasing to connect at one particular type of interface does not change this.

In stating that connection is inescapable, I do not mean to suggest that all patterns of connection are equitable or equivalent in form, function, or impact. Connection does not operate independent of variables such as race, class, gender, ability, or sexual orientation; digital augmentation is not a panacea for oppression, and neither has nor will magically eliminate social and structural inequality to birth a technoutopian future. My intent here in focusing on broader themes is not to diminish the importance of these differences, but to highlight three key points about digital social technology in an augmented world:

1.) First, our individual choices to use or reject particular digital social technologies are structured not only by cultural, economic, and technological factors, but also by our social, emotional, and professional ties to other people;

2.) Second, regardless of how much or how little we choose to use digital social technology, there are more digital traces of us than we are able to access or to remove;

3.) Third, even if we choose not to participate in digital social life ourselves, the participation of people we know still leaves digital traces of us. We are always connected to digital social technologies, whether we are connecting through them or not.

Next week, I’ll continue the conversation by examining the ways that this inescapable connection serves to complicate two prevailing discourses of privacy, both of which assume autonomous individuals as subjects and, in so doing, mask larger issues of power and inequality.

Whitney Erin Boesel (@phenatypical) is a graduate student in Sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Performance image by Neil Girling, http://www.theblight.net. Used with permission.

Modernized Rockwell image by William George Wadman, from http://fadedandblurred.com/blog/great-art-for-a-great-cause/

Shadow image by yalayama, from http://braingasmic.tumblr.com/post/22348601967/how-pcbs-promote-dendrite-growth-may-increase-autism

Kids image from http://www.eyesonbullying.org/about.html

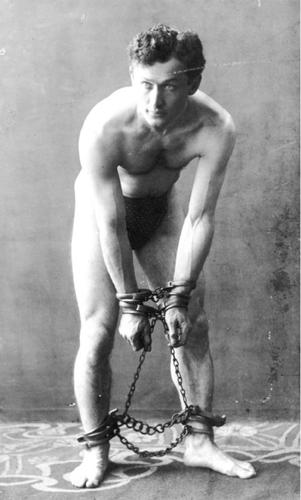

Houdini image from http://www.thestar.com/article/914083–houdini-s-inescapable-influence

Comments 7

Luis — May 29, 2012

Nothing deep to add at the moment; but wanted to say that this is great - a much needed collection of ideas that I have seen floating around but not put together in one place like this. I look forward to the next installment.

A New Privacy, Pt. 2: Disclosure (Damned If You Do, Damned If You Don’t) » Cyborgology — June 13, 2012

[...] month in Part I (Distributed Agency and the Myth of Autonomy), I used the TtW2012 “Logging Off and Disconnection” panel as a starting point to consider [...]

My Breakup With Facebook: a reflection » Cyborgology — July 6, 2012

[...] idea that “opting out” has a cost isn’t a new one on this blog and has been better written-about and better theorized than this piece can or intends to do. My point is that yeah, there is indeed a [...]

A New Privacy, Part 3: Documentary Consciousness » Cyborgology — July 19, 2012

[...] Part I this essay, I considered the fact that we are always connected to digital social technologies, [...]

A New Privacy: Full Essay (Parts I, II, and III) » Cyborgology — August 6, 2012

[...] Part I: Distributed Agency and the Myth of Autonomy [...]

Augmented (Im)mortality » Cyborgology — February 21, 2014

[…] live through the end of 2016, she will even be older than my grandmother (and, as I mentioned in my very first post for Cyborgology, my grandmother and the Internet never really clicked). My cat likes the laptime […]