On constructing a lesson plan to teach Pinterest and feminism

I teach sociology; usually theoretical and centered on identity. I pepper in examples from social media to illustrate these issues because it is what I know and tends to stimulate class discussion. It struck me while reading arguments about Pinterest that we can use this “new thing” social media site to demonstrate some of the debates about women, technology and feminist theory.

We can view Pinterest from “dominance feminist” and “difference feminist” perspectives to both highlight this major division within feminist theory as well as frame the debate about Pinterest itself. Secondly, the story being told about Pinterest in general demonstrates the “othering” of women. Last, I’d like to ask for more examples to improve this as a lesson plan to teach technology and feminist theories. I should also state out front that what is missing in this analysis is much of any consideration to the problematic male-female binary or an intersectional approach to discussing women and Pinterest while also taking into account race, class, sexual orientation, ability and the whole spectrum of issues necessary to do this topic justice.

“What’s a Pinterest?”

Before we begin, let me very briefly explain what Pinterest is [or read a better summary here]. Likely, most readers of this blog already have some experience with the site. Simply, one can post collections of images of things you come across on the web to the site; that is, one “pins” these images to various “boards” you can create under your name. Think of something you like, say, landscape photography. You can pin such photos to your “landscape photography” board and search other people’s boards for the same. The usefulness of the site comes immediately into focus when you are looking to purchase something: you can find dozens of photos of a type pinned by other users. The site has been especially useful for things like wedding planning, where one can collect cakes, centerpieces, dresses and so on that one likes.

The site has taken off, driving more customers to retail sites than “Google+, YouTube and LinkedIn combined.” People spend lots of time on Pinterest, too. In fact, the average user spends about thirty times as many minutes on Pinterest than Google+.

The next step in the typical tech-site-Pinterest-description is to go on and on about how woman-heavy the site is. Current statistics show that the site is 70-80% female, and a perusal of the main page usually reminds users of this. While the female-centeredness of the site is sometimes overstated, it also should not be dismissed.

And, no surprise, the tech community, which is still a boys club, has been terrible at writing about how people, especially women, use Pinterest. The site has been used as an excuse to make fun of women, stereotype women as shoppers, dismiss the site as overly gendered and anger some of the feminist blogosphere.

Of course, there is no one single feminist position on Pinterest or anything else. Some have celebrated and some have critiqued Pinterest as a safe space for femininity on one hand and also a sometimes troubling version of femininity on the other. This is a useful rehashing of a fundamental theoretical distinction we can make within feminist theory: difference versus dominance feminism.

Difference versus Dominance Feminism

The “difference” perspective holds that there are fundamental differences between men and women that should be respected and celebrated. Traditionally, in the non-feminist sense, differences have been used to justify male dominance. A famous case is Kohlberg developing his stages of moral development using a standard created by studying just men. He found that men typically scored higher than women on his scale and therefore men, on average, are more moral than women. One of his colleagues, Carol Gilligan, had a different take. In her book, In a Different Voice (1982), Gilligan notes that men and women have different ethics: men an ethic of justice and women an ethic of care; each not better or more moral than the other. We can consider this a paradigmatic version of difference feminism; that the differences between men and women are more fundamental than the inequalities those differences take on socially. The solution is to value that which makes women different.

“Dominance” feminism holds that those differences are themselves a result of patriarchy and to celebrate them is to celebrate the dominance that created them. Catherine MacKinnon, for example, argues that many sex differences, especially with respect to sexuality, are constructed by a patriarchal society in such a way as to reproduce these inequalities. This perspective holds dominance as more fundamental than difference, and thus the strategy is to critique both the socially-constructed differences between men and women and also the systems of oppression that created them.

This is a far too short overview of these two perspectives (which, of course, are not the whole of feminist theory!) but enough to begin applying examples from the Pinterest debate.

The difference perspective tends to view Pinterest as something distinctly feminine and therefore something to celebrate. As Tracie Egan Morrissey writes, Pinterest “is giving ladies what they want”; which is the whole point. When visiting the site, one quickly notices the refreshing “lack of misogynist content.” Amanda Marcotte states that “the pink and girly exterior of Pinterest works as a jerk force field, keeping the most piggish men away.” Women are using the site and enjoying it and spending lots of time there and that is a good thing. [In the comments, it would be great to get more examples of posts, papers, essays taking on this perspective.]

From the other side come those who view the type of femininity on Pinterest as itself problematic to some degree. The dominance perspective does not view the fact women are collectively doing something as essentially good, but the starting point of critique. Some view Pinterest as exemplifying a particularly juvenile and defanged version of women and empowerment that is ultimately more appealing to men; a critique that has been laid on so-called “domestic” or “cupcake feminism”; aka “the Zooey Deschanel problem.”

Perhaps the most biting critique of the site I have read is Bon Stewart’s argument that Pinterest creates a Stepford Wife version of identity that is hollow and uncreative. While not explicitly “feminist” in language, the argument is that what happens on social media sites, even those women enjoy, can be problematic. [Again, please send along more arguments from this perspective.]

To be fair, those taking on the “difference” position above are not responding to the dominance arguments but to the general tech-writer-trend to dismiss the site because of the number of women using it. In fact, this demonstrates another fundamental feminist theoretical point.

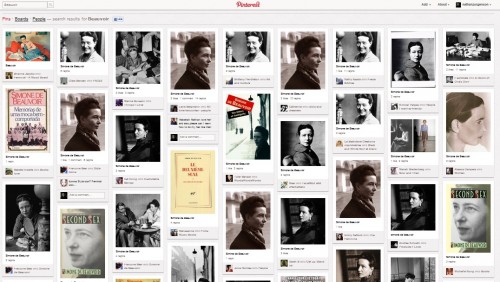

Pinterest, Beauvoir and the “Othering” of Women

The difference-feminist arguments above had to remind the tech world that a site should not be dismissed because women are using it; rather, this is precisely what makes it important. The cultural conversation around Pinterest has followed that similar path perhaps best outlined by Simone de Beauvoir in The Second Sex (1949). There has been a historical trend to view the male as “natural,” devoid of gender and able to stand in for all of humanity (remember Kohlberg only using males to construct a scale applied to everyone). Another example is the continuing usage (especially in tech-writing in the year 20-f’n-12) of male pronouns to stand for humans in general. As Beauvoir states,

In actuality the relation of the two sexes is not quite like that of two electrical poles, for man represents both the positive and the neutral, as is indicated by the common use of man to designate human beings in general; whereas woman represents only the negative, defined by limiting criteria, without reciprocity.

This othering means that websites comprised mostly of men are seen as “neutral” and those that have even the slightest hint of femininity come to be seen as thoroughly saturated with gender; indeed, Pinterest has almost come to be defined by it.

Take Wikipedia: 87% of its contributors are male; a bigger discrepancy than Pinterest by any count. However, when discussing Wikipedia, it certainly is not the norm to go on and on about how male the site is. Instead, it is far more common for the site to be praised for its “neutral point of view.” Usually-male tech writers describing the male Wikipedia have convinced themselves that the site is neutral and thus useful to all of humanity. Pinterest, on the other hand, is implicitly, and sometimes explicitly, dismissed as merely female.

Even the description of how feminine Pinterest actually is can be overstated. Using Pinterest for the past month or so, I have noticed a great diversity in content. Yes, people post about cupcakes, but architecture, food, photography, design and lots of other things are popular, too. As Rebecca Hui states, “Pinterest is, very simply, a place for pretty things, and last I checked, beauty wasn’t gender-specific.”

In fact, over in the UK the majority of Pinterest users are male. Is the UK press going on and on about how male Pinterest is? (Of course not; remember, ‘male’ is thought to be neutral).

—

It seems that Pinterest can be effectively used to illustrate at least these two points when teaching feminist theory: the Dominance/Difference divide and the Othering hypothesis. I hope that these perspectives also help us understand Pinterest and how the site is discussed in general.

Last, I hope others can help me with this lesson plan and provide more links/examples and other feminist perspectives I have not yet mentioned. Again, the articles I have linked to and my own analysis do not problematize the male-female binary. And these analyses are rarely intersectional or queer in nature. Perhaps these perspectives have not yet been written up, or, more likely, I don’t know how to find them. How else can the conversation be improved, especially with the goal of using all of this as a teaching tool?

Comments 50

Michelle Moravec — March 5, 2012

I really like this and would love to se you integrate with ideas about identity curation on facebook, in which there seems to be more gender equitable participation rates. Does "liking" something function in the same way as "pinning?" In a sense they are both curatorial identity moves. I've also been thinking about curating as creating in an attempt to understand/bridge the perceived gender divide

sallyapplin — March 5, 2012

Interesting post! Do you know if all users of Pinterest that are reporting as female actually are? Or if all users of Wikipedia reporting as male actually are? How many "Trojan horse" men or women are on these sites? Just curious.

linda layne — March 5, 2012

Loved your piece. Especially the cross-cultural comparison with the UK.

Should work great for teaching. You might also find the following of interest:

the book Feminist Technology. 2010 Layne, Vostral and Boyer eds. University of Illinois Press.

and the related blog

Feminist Technology blog: http://www.press.uillinois.edu/wordpress/?cat=84

Wessel van Rensburg (@wildebees) — March 5, 2012

Great post.

Although I have not read everything that's been written about Pinterest in the US, the articles that I have, have been in the tech blogs. Pinterest is the fastest independent site to 10 million users ever. Faster than Facebook. Neither Facebook, nor Twitter, nor MySpace had such a gender bias in the US. So that might explain some of the talk about gender. Although, not all of it.

Erin CB — March 5, 2012

Thank you so much Nathan! This is a great way to teach some of the essential concepts of feminist philosophy. I'm starting a new pinboard for lesson planning. :-)

Shauna Lee Lange — March 5, 2012

Actively collecting images on these exact topics. http://www.pinterest.com/shaunaleelange (see "Images for the NOW Conference" board).

Nina Mehta — March 6, 2012

Hello. I shared a link to this post with a group of Human-Computer Interaction design Master's students at Indiana University posing a few questions. Maybe they'll have some thoughts: http://interactioncultureclass.wordpress.com/2012/03/06/feminism-and-pinterest/

Feminism and Pinterest « Interaction Culture: The Class Blog — March 6, 2012

[...] http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2012/03/05/pinterest-and-feminism/ Like this:LikeBe the first to like this post. [...]

wilmont_proviso — March 6, 2012

Very interesting article. I have never heard of Pinterest, but I will certainly check it out. As far as the issue of difference vs. dominance feminism, I think it is a bit of both, it just depends on what is your perspective, who you are, and what are your interests.

One thing interesting about such feminisms is that there is a tendency to look at women as if they are special; being an "other" makes them unique. And a downside to men being considered "neutral" is that it makes men invisible and takes away from their uniqueness. If women are unique (and I agree that in many respects they are), are not men also unique (in some respects)?

wilmont_proviso — March 6, 2012

I forgot to add:

Your point: "In fact, over in the UK the majority of Pinterest users are male. Is the UK press going on and on about how male Pinterest is? (Of course not; remember, ‘male’ is thought to be neutral)."

This is precisely one problem (among many) that plagues the gendering of men: that men are not important, that men are invisible.

But, is it not ironic, that most of the gender articles on The Society Pages are about women? Again, men are invisible and to be ignored.

Hello Ladies — March 7, 2012

Thought you'd be interested in this board "The War on Women." http://pinterest.com/hello_ladies/the-war-on-women/

doc mcgrail — March 7, 2012

At the DML2012 conference in San Fran last week there was a really interesting panel on gender equity in digital literacies. What the panelists described (among grade-school kids)was a definite gender difference on scales of "depth" when it came to literacies involving databases and robotics and other "hard" computational skills (vs. the "soft" computational skills which they called "expressive" forms including vidding, where women showed more "depth"). "Depth" was defined as 6 or more experiences/projects.

The very cool panelist who talked about "vidding" and girls demonstrated a somewhat naive "difference" feminist approach to the problem of the gender divide that permeated the entire conference. That is, they didn't explictly or implicitly acknowledge that there is a hierarchy of digital literacies and the computational ("hard") skills are at the top, while the "expressive" ones are lower in the pecking order. I am thinking of the "shadow work" of shopping and how it's both essential and dismissed as unnecessary.

So while I love the notion of a shared "safe" space in Pinterest, I think it's really important to notice that Wikipedia is inhabited by men, and that's where people go for information--for "authority."

Thanks for getting me to think more about this.

Pinterest and Feminism » OWNI.eu, News, Augmented — March 8, 2012

[...] This article originally appeared on Cyborgology. [...]

AZ — March 10, 2012

I'm a man, I enjoy lots of what I've seen on Pinterest, and I really like the concept. But it does seem undeniably, non-neutrally "womanish" to me, and it's not about the presence of recipes or pink images or a lack of depth. Let's get real. It's simply this: You get a nice post on music, another on architecture, another on how to prepare a great meal . . . and then one about how hunky David Beckham is. That sort of thing instantly and expressly takes the Pinterest experience out of the realm of gender neutrality, and, frankly, gives a creepy feeling of discomfort and "unwelcome" to a heterosexual man, as though one has just accidentally stepped through the wrong door into the ladies' room. Nothing wrong with that, of course, but let's not pretend that sort of post (and similar things) can exist comfortably in a gender-neutral medium. In my opinion Pinterest is not gender neutral, and doesn't strike me as being concerned at all about being so.

squirrel — March 10, 2012

You mention you're lacking in any queer analysis here, which I can't not apply when I think about difference feminism: difference feminism falls apart as soon as you de-naturalize the gender binary. You can't be a believer in inherent differences between men and women and also believe that those genders are artificially constructed and not the only possibilities, you'd get quickly tied into knots.

On the other hand, de-valued constructs like femininity can become sites of active resistance, identity, and reclaimation. And criticizing women for their choices to comply or not comply with the power structures in their lives is a losing game that only reinforces those same power structures you thought to attack. Not all of femininity is worth celebrating, but criticizing it works to ill ends because it brings the focus back to what women are doing wrong and not the system of oppression itself.

So I guess my problem here is that I think "Difference feminism" is predicated on some dangerous and misguided ideas about gender. But when you talk about the views of difference feminism on pinterest, I'm pretty okay with them. On the other hand, I agree with the ideology you attribute to "Dominance feminism", but the views on pinterest you attribute to them are pretty crappy. And that dissonance gives me a weird feeling about this whole post.

I've got no links for you though, sorry.

ben — March 10, 2012

"In fact, over in the UK the majority of Pinterest users are male. Is the UK press going on and on about how male Pinterest is? (Of course not; remember, ‘male’ is thought to be neutral)."

this must be 'feminist logic'. lets say there is 1000 users of pinterest and 800 are female and 200 are men and because of this the content has a heavy female bent to it. now maybe there are 4 UK users and 3 of them are men and 1 of them is a woman. why would the UK press talk about how male pinterest is? extreme example but the UK press is going to judge pinterest by the overall content and not the demographics of UK users.

Maria — March 10, 2012

Ben: Actually, out of 200,000 UK users 56% self-report as male while 83% of US user self-report as female. You could just have followed the link and seen that. That's not a very impressive majority imo so can see why people wouldn't make an issue of it.

If you look at the trending interests presented in the same link, the difference between UK and US users in terms of content is more obvious.

I decided to check This BBC article

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-17204313

both takes note of how female pintrest is, and how male the UK userbase is.

I tried to find something similar on a mainstream site about Reddit, which skews male 12:2, but couldn't. This could be because Reddit is older and I couldn't find much about it when it was just taking off, period. But I really doubt there is an article out there going, hey guys, look at all this male oriented new site.

Stephanie Medley-Rath — March 10, 2012

Pinterest makes the domesticity of women visible. Is that problematic? Maybe. Is that empowering? Maybe. I view pinning like I view scrapbooking (and many scrapbookers were early adopters to Pinterest), in that, it does neatly conform with gender roles while at the same is a space for women to demonstrate their power. Pinterest is a space where what women were already doing becomes visible and becomes more social. Women already exchange recipes. We don't need Pinterest for that. Women already save pages from magazines of decorating, wedding, baby, and cooking ideas. Again, we don't need Pinterest for that. Pinterest makes these activities public and more easily shared.

Many pins link back to women-owned websites and stores, while others link back to women-written (and owned) blogs. Perhaps this is just me being a "cupcake feminist," but I think that Pinterest is a great way to discover women-owned and women-created content on a male-dominated web. (And many of these women-owned websties, stores, and blogs are created by self-proclaimed WAHMS,which is a whole other post/analysis).

Doing gender, clearly, is visible on Pinterest, but what is really interesting is how gender intersects with race and income. 28% of Pinterest users have household incomes of at least $100,000 (http://news.yahoo.com/13-pinteresting-facts-pinterest-users-infographic-163607807.html). Pinterest is not nearly so much about doing womanhood, but doing a very specific type of womanhood (White, upper-middle class, motherhood).

I find the hows and whys of Pinterest fascinating. I'm pretty sure my response here is a bit all over the place because the whole project sends my mind running in a hundred directions. There is so much sociologically going on with Pinterest.

Epicene Cyborg — March 11, 2012

[...] Pinterest and Feminism. [...]

Hackernytt | Om startups och allt som hör till. På svenska. | Pinterest and Feminism — March 11, 2012

[...] Pinterest and Feminism [thesocietypages.org] poäng | Postat mars 11 av Erik Starck [...]

Pinterest: Now Das Futurist « vivek semiotics — March 11, 2012

[...] Maybe, but newsflash, websites are businesses. And Pinterest has a resounding majority of women users and pinned items are more often than not household decor, hairstyles, or fashion, just check [...]

carole — March 11, 2012

I love AZ's post:

"and then one about how hunky David Beckham is. That sort of thing instantly and expressly takes the Pinterest experience out of the realm of gender neutrality, and, frankly, gives a creepy feeling of discomfort and “unwelcome” to a heterosexual man"

Welcome to our world AZ! Everywhere you look women are sexually exploited in society - which takes me out of the realm of gender neutrality, and gives me a creepy feeling also....

Fascinating post on Pinterest and Feminism | Opening New Texts — March 12, 2012

[...] re-post: Go here (http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2012/03/05/pinterest-and-feminism/) for a spectacular discussion on the gendered nature of social media sites. My favorite part: When [...]

3-16-12: Social Media and Gender « Maryland Morning with Sheilah Kast — March 16, 2012

[...] One never knows which social networks are going to connect to the zeitgeist and draw users by the millions. The latest is Pinterest. And it’s igniting discussions not just about technology, but about gender. [...]

Pinterest and Feminism » Cyborgology | Exploring Feminism | Scoop.it — March 16, 2012

[...] background-position: 50% 0px; background-color:#222222; background-repeat : no-repeat; } thesocietypages.org (via @SOCIALogia) - Today, 7:58 [...]

jaz — March 24, 2012

I agree with what squirrel previously posted in terms of critiquing your article with the whole difference and dominance feminism thing. The Othering part seems very well-thought out to me and on the whole I found this article very interesting, but the first half needs some work, I think.

In addition to what has been said, I would also encourage you to emphasize more (as in more often, more clearly, and more from the outset) that feminist theory is NOT just dominance vs difference, because that refuses a lot of other subtler variations and complications like Foucault, for example. I would also say that while labeling these "two feminisms" can be useful when you're first learning and beginning to understand them, the labeling doesn't sit well with me when you use them repeatedly and fixedly--again, this can negate feminist theorists who are, say, part difference and part dominance.

But all in all, very interesting area of exploration and some great thoughts in there!

Pinterest and Feminism « n a t h a n j u r g e n s o n — April 2, 2012

[...] This post originally appeared on Cyborgology – read and comment on the post here. [...]

JennyWillknitt — April 5, 2012

Nathan- I read your excellent article on faux vintage photography and found this one afterwards (also very thought provoking). I'm female and I use pinterest, but I never thought of it as a site for shopping, I'm a fairly new user and haven't looked on the site that much, but for me I use it as a way to make a digital sketchbook and collect resources that are an inspiration for art projects now or in the future- it is particularly useful for video, as I can only print stills out to put in a sketchbook, but on Pinterest I can create a digital equivalent where the moving image can be viewed after clicking through. It's ecologically sound as I don't waste paper printing out all of this stuff and is easy to manage and organise, so it works well. If you're wondering my boards are new and so relatively empty, but my pins are stills from Soviet era sci-fi films, Kubrick and Lynch, brutalist architecture and zoetropes. Not a cupcake in sight.

I guess my point is that it will be very interesting to see if a multitude of different uses appear over time- for me Pinterest is the wall of the artist's studio I can't afford, there's nothing gendered about a pinboard (surely the concept for the interface and name), but there is something that is read as gendered about the idea of scrapbooking- that it is a hobby and a feminine one at that.

The background and layout of pinterest are fairly utilitarian, as a pinboard would be on the break room wall at work. The site uses pale greys and gridded layouts, in fact only their choice of font for the logo (not even colour as red isn't seen in the West as being particularly gendered) could be considered as distinctly feminine, given the use of a cursive script.

I wonder if the creators of the site envisaged it being used by a multitude of users to pin a far wider range of sources than is typically seen on the home page. I will happily use it to pin articles of interest- in this case I don't care what the picture the site displays is, more the important functional aspect of being able to collect and organise digital research and easily locate it at a point in the future when I want to review it.

Maybe I'm misusing the site, or straying for its intended vision...

In the future will the site be used in a wider way- for activism, religious practice, humour, promotion of unsigned bands, events etc? It has the potential to be used like this, much in the same way as facebook, but I hope that there are more creative uses for it, more intellectual ones too than the majority of things that currently crop up on the homepage. Above all I hope there is a shift, both on the site and off of it to draw awareness to the fact that the reason why the site 'feels' feminine is because its users are predominantly feminine, and that there is nothing (bar the font) inherently feminine about a grey website with a red logo that you can use like a digital cork board.

I read some articles a while ago when I was waiting for my pinterest account to be activated about Pinterest for men, they worried me, there are a lot of things online that are similar to this:

http://abcnews.go.com/Technology/pinterest-alternatives-men/story?id=15835055#1

Pinterest and Feminism » Cyborgology | FEMEN Rights | Scoop.it — April 11, 2012

[...] background-position: 50% 0px; background-color:#222222; background-repeat : no-repeat; } thesocietypages.org - Today, 8:46 [...]

Social Media and Gender: The Paradox « amandayam — May 7, 2012

[...] and cursive, red font. The initial page has images of décor, flowers, and more feminine things (Jurgenson). The overall design of Pinterest targets the stereotypical women, becoming a safe space just for [...]

Collisions with Reality » Blog Archive » Another Invisible Woman on the Internet — June 4, 2012

[...] event that had me thinking about the invisibility of women on the internet. Wikipedia editors are overwhelmingly male*. The vast majority of tech blogs and photography blogs that I read are written by men. And the [...]

Anthropology and Pinterest Part 2 | Anthropology Report — June 22, 2012

[...] Pinterest and Feminism, Nathan Jurgenson We can view Pinterest from “dominance feminist” and “difference feminist” perspectives to both highlight this major division within feminist theory as well as frame the debate about Pinterest itself. Secondly, the story being told about Pinterest in general demonstrates the “othering” of women. Last, I’d like to ask for more examples to improve this as a lesson plan to teach technology and feminist theories. I should also state out front that what is missing in this analysis is much of any consideration to the problematic male-female binary or an intersectional approach to discussing women and Pinterest while also taking into account race, class, sexual orientation, ability and the whole spectrum of issues necessary to do this topic justice. Thanks to Jane Henrici for the heads-up on this one. Cyborgology, 5 March 2012 [...]

Emily Schwarting — July 27, 2012

I think it would be interested to talk about how Pinterest does a few things:

1) is GREAT for capitalism, and is making consumers out of people who otherwise may not have been...as much. I'm not sure the implications of making women into such consumers so easily.

2) Weddings. More and more college girls who aren't even engaged have Pinboards with hundreds of pins for the future wedding. I must ask, are young girls indulging in the traditions of marriage and taking away from their studies?

3) Work out tips. Various workouts are often shown along with a picture of a perfect woman, with perfectly toned abs. I wonder what this is doing for young girls self-esteem.

4) Perfection. I don't think it will ever be good for women's statuses to spend large amounts of time obsessing over things that are perfect. (Perfect homes, perfect recipes...)

5)Perfect mothers. Pinterest makes you feel like a bad mom. The DIY is only accessible, I promise you, to the stay at home mother. Many mothers, like myself, leave Pinterest feeling inadequate in every realm, but mostly because we didn't give our one year old a perfectly color coordinated DIY birthday party. What mothers don't pay for in mass produced items because they are doing it themselves, they are paying for in labor. I don't know who has time to do 100 hours of DIY for a one year old's birthday party, but they all seem to be scouring Pinterest and making me feel like crap.

Marian Evans — November 29, 2012

This article and discussion made me think, because I use Pinterest as a site for feminist activism and as an extension of own work as an artist (film, theatre) and activist: http://pinterest.com/wellywoodwoman/. And I'm not alone. Would love to see another article about women's activist uses of Pinterest.

The Boyfriend’s Guide to Pinterest | Modern Primate | man, that's deep — December 5, 2012

[...] on Pinterest and Feminism, check out Nathan Jurgenson’s article on The Society Pages athttp://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2012/03/05/pinterest-and-feminism/Music: Talk Show Boy – “Testosterone” Gablé – “humm ok” Latché [...]

Sampling Pinterest | SociologyFocus — December 10, 2012

[...] based on the content of Pinterest feeds as summarized in the above photo (see for example, here and [...]

(Final Project) Pinterest and Feminism | rebeccah quist — December 15, 2012

[...] order to rectify them and give women a chance to succeed unhindered by society-imposed limitations. This blog post by Nathan Jurgenson does an excellent job of further explaining each feminist perspective and how [...]

(Final Project) Annotated Bibliography | rebeccah quist — December 15, 2012

[...] Jurgenson, N. (2012, March 5). Pinterest and feminism. In The Society Pages. Retrieved December 11, 2012, from http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2012/03/05/pinterest-and-feminism/ [...]

On class distinctions and being (un)pinterest-fabulous. | allwryledup — March 6, 2013

[...] pinterest and feminism [...]

Pinterest and Playing Gender » Cyborgology — April 5, 2013

[...] in the US, Pinterest has come to be understood as gendered massively female/feminine/femme. As Nathan Jurgenson noted in his essay on Pinterest and feminism, this has resulted both in misogynist mocking and devaluing of Pinterest as a female/feminine [...]

Accidentally in Code » On Building The Things You Want — June 10, 2013

[...] the drivers of consumer spending. But Pinterest is derided as being “girly” – (fascinating article - it’s not actually that dominated by women, Wikipedia is far more dominated by men, but [...]

Sampling Pinterest | Stephanie Medley-Rath, Ph.D. — July 7, 2013

[...] Pinterest has been a source of interest to sociologists and other scholars, and has mostly been criticized based on the content of Pinterest feeds as summarized in the above photo (see for example, here and here). [...]

Cyborgology Turns Three » Cyborgology — October 26, 2013

[…] 7. Pinterest and Feminism […]

Pinterest Just Hired The Man Behind Axe’s Infamously Sexist Ads | Omaha Sun Times — July 23, 2014

[…] appeal to male users on Pinterest, Odell’s thesis — which spawned academic papers and blog posts galore — may prove […]

전세계의 최신 영어뉴스 듣기 - 보이스뉴스 잉글리쉬 — July 23, 2014

[…] appeal to male users on Pinterest, Odell’s thesis — which spawned academic papers and blog posts galore — may prove […]