Rob Horning has been working on the topic of the “Data Self.” His project has a close parallel to my own work and after reading his latest post, I’d like to jump in and offer a conceptual distinction for thinking about the intersection of the online/data/Profile and the offline/Person.

The problem is that our online presence is too often seen as only the byproduct of our offline selves. Sometimes we talk about the way online profiles are passive reflections of who we are and what we do and other times we acknowledge our profiles are also partly performative adjustments to the “reality” of the person. However, in all the discussion of individuals creating this content what is often neglected is how the individual, in all of their offline experience, behavior and existence, is simultaneously being created by this very online data. We cannot describe how a person creates their Profile without always acknowledging how the Profile creates the person.

Let me begin by offering some useful terminology: I use the term profile (lower-case ‘p’) to mean our presence on any specific web service, e.g., our Twitter or Facebook profiles. I use the term Profile (capital ‘P’) to refer to the aggregate set of our entire online presence across all profiles including data we have uploaded or others have gathered.

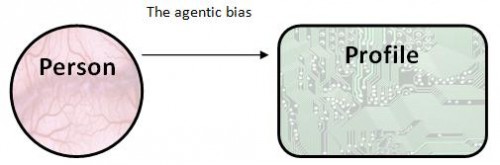

And let me call the “agentic bias” the tendency to conceptually grant too much power to individuals to create their online Profiles by neglecting the ways in which individuals are simultaneously being created by their digital presence. Lots of social media writing, academic and popular, looks like this:

Many otherwise terrific articles about the self, identity and social media suffer from this bias. In a forthcoming post, I plan on going through a list of some prominent examples. For now, I want to focus on responding to and joining in on Rob Horning’s work on “the data self.” He makes many useful points, but fundamentally conceptualizes “data” and “self” in a manner in which the latter causally precedes the former (I happen to know he doesn’t like that ‘latter-former’ turn of phrase).

In this article, Horning describes how we “convert ourselves into data”; we are “monitoring [our] vital statistics and uploading them for analysis and aggregation.” Further, Horning goes on to say,

“data collection is slowly becoming the ideological basis of the self”

“interactions within social networks are now easily captured”

“The assumption is that by letting Facebook capture and process everything, a more reliable version of the self than our own memory can give us will be produced.”

And Horning cites Facebook as saying “the Timeline to be a place for self-expression: A way for users to reveal who they are and what their lives are about”

(all emphases mine)

The “data self” as described here has everything to do with how self creates, produces, collects and revels itself through data. This is indeed an important concern, and, to be clear, there is far more I agree with than disagree with in Horning’s analyses.

However, so far, lots of attention has been given to how the self creates the data, what I called the agentic bias above; but what about when this data also creates the self? Both considerations must be simultaneously taken into account to understand either.

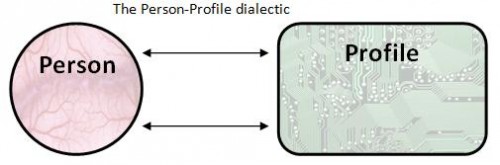

Instead of an agentic bias, I propose a dialectical understanding of the causality between the individual/offline/self and the data/online/Profile:

PJ Rey and I have been arguing something similar since we started this blog. Indeed, the name Cyborgology makes explicit reference to Donna Haraway’s cyborg theory of bodies and technology as enmeshed. Further, I have written extensively on what I call “augmented reality,” the perspective that views the on and offline as enmeshed, opposed to the “digital dualist” bias to view atoms and bits as separate. To fully theorize the self from the “augmented” perspective, one must rigorously take into account the data-flesh-enmeshment from both directions.

For example, in a recent essay I describe how one great power of social media is not just what happens to us when logged in uploading data about ourselves and our lives, but also how sites like Facebook change how we view the world even when logged off and not staring at some glowing rectangle; what I call The Facebook Eye. To only focus on how the self produces data is to miss how data influence our experience of the world; how we behave within it and how data creates that same self that creates the data.

Let’s take some concrete examples:

When listening to music on Spotify, a streaming service that syncs with and publishes to one’s Facebook profile, I am publishing that listening-data to Facebook for others to see. It becomes part of my Profile. But to end the story here is to suffer from the agentic bias. Let’s put the other causal arrow back in and think dialectically: because my Profile contains listening behaviors that I know are being judged by others, I may choose to listen to slightly different music to “give off” the impression I wish to portray. More than just a better-than-accurate presentation of self, the fact that the Profile exists changes my experience and behavior as a person.

If you plan on taking photos while on vacation and posting them to Facebook, might you choose to do slightly different things? Walk different paths?

But we must go further than just potential changes in behavior. What I find most interesting is how the Profile changes our experience of that behavior.

Maybe you wouldn’t change the songs you listen to or what paths you travel when on vacation simply because of social media self-documentation. However, the fact that one can increasingly document their life certainly changes how we experience the world (much more on this point here).

We experience a concert differently when we know we can post photos on Facebook and videos on YouTube; hence the music-venue-plague of glowing document-screens held high instead of hands. We see the food we just prepared differently when we know we can post a photo of an especially delicious-looking meal to Facebook. As I’ve posed before: think of traveling with and without a camera in your hand: the experience is at least slightly different. Today, we are always living with the camera in-hand; we can always document our lives via status updates, tweets, check-ins, photos, videos, etc. Like those on reality TV, social media users are deeply influenced by the fact of near omnipresent documentation potential.

Taken to the extreme, the conceptual opposite of the agentic bias would be a structure-bias that views people as only the result of our Profiles. Once, on a subway, I heard a woman claim that “the real world is the place where we take pictures for Facebook.” But this is probably going to far, right?

To conclude, and to provide a last probe to Rob, the implications of all this is that we cannot continue to view the Person as the temporal and causal antecedent and the Profile as something that is the subsequent result. We have clear evidence that the person is also being co-constructed by the Profile. Experience creates documentation and documentation creates experience.

Comments 33

Thomas Wendt — January 30, 2012

I think it's also important to mention the homeostatic tendencies of Person and Profile. Along with each creating the other, there seems to be a tendency on both parts to complete the other. The Person is in a constant state of uploading and filling in the gaps within the Profile to give a more complete digital snapshot of one's self. Similarly, through things like "frictionless sharing," the Profile is trying to extract information with as little user influence as possible. There is a desire for homeostasis and wholeness that I'm not sure can be achieved.

Cheri Lucas — January 30, 2012

Oh my -- this is the first thing I've read this morning and certainly has made my mind roam. Lots here that I like, much of it putting into words things I've sensed but have never tried to analyze. Or perhaps I do unconsciously, and bits of these ideas surface in my writing. I started exploring the distinctions of my offline/online selves last year and felt strongly that they were separate, as well as gave too much power to Cheri the Person, who completely controlled Cheri the Profile.

But over the year my ideas have evolved. I like reading things like this -- "the person is also being co-constructed by the Profile." I do agree.

Really fascinating stuff that helps me to formulate my own ideas. Thank you!

Dan Greene — January 30, 2012

Great post Nathan! The 'nonhuman turn' is becoming an increasingly important political project. We need to better understand the reciprocal relationships between humans, environments, and objects (data) to better understand and change the world. In my own work, I'm increasingly realizing that it's wrong to separate the agency of access (getting tools, doing things, producing data) from the objects and institutions that have access to you (monitoring data, nudging decisions, determining choices and opportunities).

Rob — January 30, 2012

This is great. Glad my posts were able to help prompt this response!

Yes, my dialectics definitely need sharpening, but I definitely agree that the Profile shapes the profile. I think identity works in our particular ideological climate by masking its constructed origins, making it seem as though the profile is always making the Profile -- making it seem and allowing us to believe that we are unique individuals and what we do in the world reflects some unalterable core within. So when Profile changes our ways of perceiving the world -- when we begin to shape our behavior in terms of what Facebook can capture -- I think we also strive to disavow that change. That urge clearly colors the way I write about social media, as you've pointed out!

I am certainly very surprised to be used as an example of agentic bias when I think of myself as having an almost cartoonish structuralist bias. I underplay the part of the story where the opportunity to share dictates what we do because I take it too much for granted that everyone sees it that way? Once you have Spotify, or whatever, it requires grooming and the reflexive grooming cancels out any preceding "innocent" or "authentic" listening behavior. Think the "authenticity" issue is basically the ideologically induced blindness to what you've called the agentic bias.

But absolutely agree that these media reshape what experience, and experience of what the self consists of; that social media services constitute the data that make up the data self in serving it to people, habituating them to seek certain forms of microaffirmation from using them. So I think that the data self is made up of data the companies create out of our raw material and other information (people who are statistically like us) as much as any data we feed into it, actively or passively. We increasingly stabilize our self-concept in terms of what social media makes possible, what sorts of rewards it can supply, and what garners those rewards.

I think the logical extension here is Facebook coming preloaded with experiences, Twitter preloaded with ordinary friends, etc.

Rob — January 30, 2012

one more point: What I was trying to get at in my posts about the "data self" is that the anchor of capitalist subjectivity may be changing from that idea of "authenticity" -- consumerism allows us to discover the unique individual really are and express it to something else that is driven by data profiling and "sharing." That is, the pleasures of identity are less about discovering, owning, and operating a particular unique self (as they were, mainly, under consumerism pre-social media); they are becoming more about mircoaffirmations in participating in networks and being accurately recognized through data patterning (we are matched with the people who can affirm us, or we can see a reflection of ourselves in what data we provide that pleases us). So that the data self is one which knows itself only to the degree that it shares data and exists within media that can guide it toward various satisfying experience and allow it to display its satisfactions dependably in formatted and readily circulatable ways.

The threat to the "data self" sort of subjectivity is not inauthenticity (the threat that tends to afflict me, make me doubt myself, etc.), but something else -- some lack of access to the network or some sort of disruption of the information flow -- the threat to the data self is the terror that Wittgenstein might have been right about their being something crucial that can't be expressed and must be passed over in silence. Interaction with Facebook, etc. perhaps reshapes subjectivity to make feel impossible to us. We are ONLY what we express and share; the possibility that something could be meaningful and unshared becomes unthinkable, unfeelable, if that makes sense.

Mike — January 30, 2012

Really great post, Nathan. I didn't read Rob as saying that the self precedes the data -- but this might be because I read a previous post where Rob references Althusser in saying that Facebook interpellates us as subjects. Still, I think you are right that this point isn't carried through all the way in places.

But I think the concept changes the way we think of the relationship between the self and the data. Taking up Althusser's formula of interpellation, we are constituted as Facebook subjects or Data Selves, at the moment of recognition, when we are hailed by our Profile, as it were, to fill it out. But this moment of recognition is prior to our response to it - in order to join Facebook, we first have to see ourselves as somehow needing to do that. And we don't actually have to be on Facebook to feel that way.

What constitutes us as subjects is the empty place on Facebook that we recognize as needing to be filled with our data - so for me, the Profile is first and foremost a void rather than the substance of what we fill it with, exemplified in the question that used to be asked "Are you on Facebook?" Or maybe also the millions of blog entries beginning with "Sorry I haven't updated this blog in awhile..." Both attest to the void and filling the void.

This void may even be imagined more abstractly as our personalized Facebook URL. We recognize ourselves as Facebook subjects when we feel the need to fill in the space that it points to.

Thomas is right about the impossibility of ever filling this space. To the extent that the actual data itself mediates our behavior, I think it is in the sense of opening up another space. Social media is continuous rather than bounded - a series where the addition of a new element can only create another void, never an end point, making the Data Self into a stream.

sally — January 31, 2012

Is this story of agency any different from someone writing in a journal? Would the journal have a "better memory" as a record than the person writing in it?

What is inherent in the digital that makes this story stronger or more different? (Besides PolySocial Reality ;-) )

Many people throughout history have kept careful analog records "for the archive" that were very likely "better" (more polished, less fully truthful, more flattering to A or B) than their lived experiences.

There are many people who have signed up to Facebook and do not have it interconnected with other apps on the web, so there is a spectrum of publishing that is happening.

In the furthest out case, there are likely individuals who are curating their lived experiences for the digital archive, but they aren't representative of everyone--at least consciously.

Our tax records, our credit card habits our health records--there is data about our lives that defines us--that we only create indirectly, have perpetual agency that we have limited control over even if we are aware of the system that is acting on that documentation.

For example, Fred Customer repeatedly purchases an item, ok, let's pick adult diapers. He happens to be buying them for a relative who is housebound. Let's add to it. Let's say the housebound person also really loves diet soda, candy and has a grandchild that they want to send toys to. Does the drugstore know this? Nope. They only know that Fred Customer purchased adult diapers, diet soda, candy and toys. What can they infer about Fred Customer? More importantly, what DO (e.g. what experience do they create from the documentation) they infer about Fred Customer and are they correct? Likely not? At the moment, that data isn't correlated with Fred Customer's health record, so they can't know if he's the one who needs all the stuff he is buying, and it isn't correlated with his Facebook. Wait, is it? He bought the diapers online through the same company. Well, now he gets ads for adult diapers and other related problems because the drugstore's ad agency thinks he buys them. Oh! They signed him up for the AARP newsletter and that group forwarded his name to an advertising list for a home elevator company, retirement condos, will writing, cemetery selection services and then those places forwarded his name to their connections and so on. All because Fred Customer helped out a relative in need. See where this is going?

The significance of documentation is its persistence. It's there for future agency to draw on time and time again and infer different experiences. Fred Customer's friends may have documentation to add to their experience of his documentation in the form of their model memories of him, but most of the world doesn't have that. He's still him in each case. So, friends have access to a different construction of Fred's "identity" than everyone else in the world does.The interpretation of the agency who ingests the documentation, if they have any impact on any real person, is the way that that documentation builds the experience/s. With agency interpreting and modifying circumstances, there could be a multiple different experiences for each documentation trail. Also, documentation doesn't say one thing to all agencies.

It's one thing to say that friends have documentation of Fred Customer that creates different experiences than what the drugstore might do to him. That said, even Fred's friends creating experience from a documentation makes a problem for him, because he has additional documentation that he doesn't want people to know about him, as we all do. But Fred doesn't get to determine what his friends' experiences are. The documentation/experience is the intersection between him and all the other agencies that he interacts with. He gets to send the first one. Each modification of the record is a composite of his interaction with other agencies, not just what he did that one time.

There is No “Cyberspace” » Cyborgology — February 1, 2012

[...] Web but is isolated from it’s effects). Instead, the Web is part of reality; it is real. As Nathan Jurgenson recently described, we are as much a product of our online profiles as a they are a product of us. Causality is [...]

There is No “Cyberspace” « PJ Rey's Sociology Blog Feed — February 3, 2012

[...] Web but is isolated from it’s effects). Instead, the Web is part of reality; it is real. As Nathan Jurgenson recently described, we are as much a product of our online profiles as a they are a product of us. Causality is [...]

What I Read This Week – 4th February - A Literal Girl — February 4, 2012

[...] The Data Self (A Dialectic) (Nathan Jurgenson) we cannot continue to view the Person as the temporal and causal antecedent and [...]

The Data Self (A Dialectic) » Cyborgology | Social media and identity issues | Scoop.it — February 5, 2012

[...] background-position: 50% 0px; background-color:#222222; background-repeat : no-repeat; } thesocietypages.org - Today, 10:20 [...]

Devon Buchanan — February 6, 2012

To put this co-construction in cartoon form (sort of): http://xkcd.com/77/

The Dissolving Mirror - A Literal Girl — February 7, 2012

[...] week I came across this piece - "The Data Self (A Dialectic)" - by Nathan Jurgenson. “We cannot describe how a person creates [...]

There is No Cyberspace » OWNI.eu, News, Augmented — February 9, 2012

[...] the Web but is isolated from it’s effects). Instead, the Web is part of reality; it is real. As Nathan Jurgenson recently described, we are as much a product of our online profiles as a they are a product of us. Causality is [...]

The Data Self (A Dialectic) « n a t h a n j u r g e n s o n — February 13, 2012

[...] This was originally posted at Cyborgology – click here to view the original post and to read/write... What Facebook knows about you, via the Spectacular Optical tumblr (click for more images) [...]

The blog of David Brake academic, consultant & journalist — March 5, 2012

[...] you, this rant which I have been saving for a while now was inspired in part by the excellence of a Nathan Jurgenson blog post which reminded me that academic blog excellence is not yet [...]

My Breakup With Facebook: a reflection » Cyborgology — July 6, 2012

[...] who and what I’m going to be. This self isn’t divorced from my non-digital self; they have each profoundly influenced the construction of each other. So please understand that I’m not suggesting that I broke up with Facebook because I found [...]

Manufacturing Memories | Full Stop — August 16, 2012

[...] question of document versus reality gets even more complicated. As media theorizer Nathan Jurgenson wrote some time ago, the relationship between, for example, Facebook profile creator and Facebook profile is not a [...]

Pinterest and Playing Gender » Cyborgology — April 5, 2013

[...] is also augmented. It isn’t something that purely informs the digital aspects of who we are; it is a dialectic as well. I believe I was genderqueer before I started roleplaying male characters with my fandom friends, [...]

WHY are people so annoying on social media? - ReferralCandy — October 3, 2013

[...] The Data Self (A Dialectic), Nathan Jurgenson offers the compelling argument that our profiles create us just as much as we [...]

0095 – london dream, condensed terms | visakan veerasamy. — October 7, 2013

[...] to invent these things myself- I can use the motifs of others. Nathan Jurgenson’s work on the dialectic data self is a great one. The concept: the Profile. Your web identity which you create and present to the [...]

Online Identity proposal – I shop therefore I am | ACM202 - Advanced Digital Imaging (blog journal) — January 11, 2014

[…] Jurgenson, N 2012, ‘The Data Self (A Dialectic)’, Cyborgology http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2012/01/30/the-data-self-a-dialectic/ […]

Politics, Ruin, and Digital Space » Cyborgology — July 26, 2014

[…] we can assume that. If our lives are augmented by digital technology, if our selves – as many of the authors here have argued repeatedly – are the result of complex interactions between […]

Jurgenson, Nathan 2012, ‘The Data Self (A Dialectic), The Cyborgology Blog | digital images — January 15, 2015

[…] http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2012/01/30/the-data-self-a-dialectic/ […]

digital images — January 16, 2015

[…] Profile: Nathan Jurgenson Jurgenson, N 2012, ‘The Data Self (A Dialectic)’, Cyborgology http://thesocietypages.org… […]