It’s a notable coincidence that Steve Job died exactly two decades after Neil Stephenson completed Snowcrash, arguably, the last great Cyberpunk novel. Stephenson and Jobs’ work exemplified two alternative visions of humans’ relationship with technology in the Digital Age. Snowcrash offers a gritty, dystopian vision of a world where technology works against human progress as much as it works on behalf of it. Strong individuals must assert themselves against technological slavery, though ironically, they rely on technology and their technological prowess to do so.

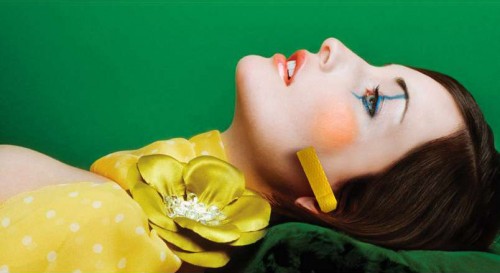

Apple, on the other hand, tells us that the future is now, offering lifestyle devices that are slick (some might say, sterile). Despite being mass produced, these devices are supposed to bolster our individuality by communicating our superior aesthetic standards. Above all, Apple offers a world where technology is user-friendly and requires little technical competency. We need not liberate ourselves from technology; there’s an app for that.

Values and style are inextricably linked (as Marshal McLuhan famously preached). So, unsurprisingly, the differences between Apple’s view of the future and that of Cyberpunk authors such as Stephenson run far deeper. The Cyberpunk genre has a critical mood that is antithetical to Apple’s mission of pushing its products into the hands of as many consumers as possible. The clean, minimalist styling of Apple devices makes a superficial statement about the progressive nature of the company, while the intuitive interface makes us feel that Apple had us in mind when designing the product—that human experience is valued, that they care. Of course, this is all a gimmick. Apple invokes style to “enchant” its products with an aura of mystery and wonderment while simultaneously deflecting questions about how the thing actually works (as discussed in Nathan Jurgenson & Zeynep Tufekci’s recent “Digital Dialogue” presentation on the iPad). Apple isn’t selling a product, it’s selling an illusion. And to enjoy it (as I described in a recent essay), we must suspend disbelief and simply trust in the”Mac Geniuses”—just as we must allow ourselves to believe in an illusionist if we hope to enjoy a magic show. Thus, the values coded into Apple products are passivity and consumerism; it is at this level where it is most distinct from the Cyberpunk movement.

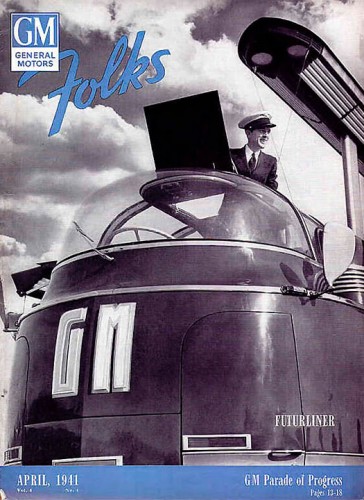

In the “The Gernsback Continuum,” William Gibson—Cyberpunk’s best-known author—makes a similar critique of 1930s Futurism / Art Deco for its naive optimism, in which the present masquerades as a Utopian future. Gibson explains:

In the “The Gernsback Continuum,” William Gibson—Cyberpunk’s best-known author—makes a similar critique of 1930s Futurism / Art Deco for its naive optimism, in which the present masquerades as a Utopian future. Gibson explains:

The Thirties had seen the first generation of American industrial designers; until the Thirties, all pencil sharpeners had looked like pencil sharpeners your basic Victorian mechanism, perhaps with a curlicue of decorative trim. After the advent of the designers, some pencil sharpeners looked as though they’d been put together in wind tunnels. For the most part, the change was only skin-deep; under the streamlined chrome shell, you’d find the same Victorian mechanism. Which made a certain kind of sense, because the most successful American designers had been recruited from the ranks of Broadway theater designers. It was all a stage set, a series of elaborate props for playing at living in the future.

Today’s popular consumer electronic devices—typified by Apple products—have revived this futurist pattern of enveloping technology in a fantastical veneer, though exchanging chrome and Bakelite for brushed aluminum and pristine white plastic. The important parallel between Gibson’s pencil sharpener and the iPhone is that, by burying the inner-workings of its devices in non-openable cases and non-modifiable interfaces, Apple diminishes user agency—instead, fostering naïveté and passive acceptance.

Jobs delivered consumers a clean, safe future in the here and now—a future which, paradoxically, brings pollution and exploitation to much of the rest of world, who are not so lucky as to indulge in this illusion (a story told in this game, which, tellingly, has been censored by Apple’s app store). The problem with this sort of fetishistic techno-Utopianism—as 30s Futurism and the Apple corporation both demonstrate—is that, by living with our heads in an idyllic future, we tend to ignore, or simply paper over, the problems of the present. In conventional Marxian terms, we might say Utopian Futurism is form of “false consciousness,” a buoyant ideology disconnected from real material conditions. Futurism is also, arguably, a post-Modern phenomenon, insofar as in implodes the present and the future. Of course, because this future has not yet happened, it is an imaginary future. In attempting to pass the present off as an imaginary future, Futurism negates both, creating a simulation (present qua future) of a simulation (the imaginary future)—what philosophers call a simulacrum. By asserting that the future has arrived, Futurism negates the real conditions of the present as well as any constructive imaginings of the future.

Jobs delivered consumers a clean, safe future in the here and now—a future which, paradoxically, brings pollution and exploitation to much of the rest of world, who are not so lucky as to indulge in this illusion (a story told in this game, which, tellingly, has been censored by Apple’s app store). The problem with this sort of fetishistic techno-Utopianism—as 30s Futurism and the Apple corporation both demonstrate—is that, by living with our heads in an idyllic future, we tend to ignore, or simply paper over, the problems of the present. In conventional Marxian terms, we might say Utopian Futurism is form of “false consciousness,” a buoyant ideology disconnected from real material conditions. Futurism is also, arguably, a post-Modern phenomenon, insofar as in implodes the present and the future. Of course, because this future has not yet happened, it is an imaginary future. In attempting to pass the present off as an imaginary future, Futurism negates both, creating a simulation (present qua future) of a simulation (the imaginary future)—what philosophers call a simulacrum. By asserting that the future has arrived, Futurism negates the real conditions of the present as well as any constructive imaginings of the future.

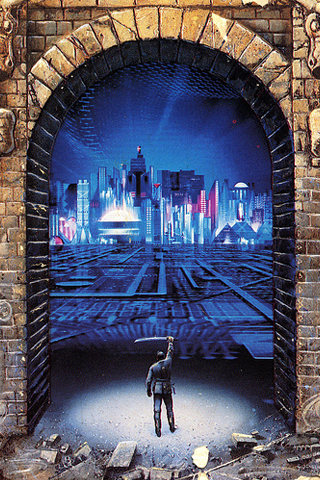

Even before the Internet Age blossomed, the Cyberpunk movement anticipated the potential for this new breed of (cyber-)Utopianism and offered itself as a sort of vaccine against the irrational exuberance that we, nevertheless, witnessed in the 1990s. The genre is characterized by the marriage of a deep interest in (and embrace of) modern technology with pessimism regarding the potential social consequences of this technology’s pervasive use. Far from being techno-evangelists, Cyberpunk authors warn against a future they nonetheless portray as inevitably. Loss of individual liberty is almost invariably a central concern—however, scenarios created by Cyberpunk authors tend to promote an anarchist (as opposed to libertarian) concept of freedom. Stephenson, in particular, portrays worlds in which government institutions have become ineffective at regulation so that life or death decision are left to whims of market forces. In light of such conditions, Stephenson details a world with stark contrasts between those who have power and status and those left to languish on the margins. In Snowcrash, for example, a wealthy media baron drugs tens of thousands of people and drags them off to an enormous chain of rafts where they are used as living hosts to breed a virus. Under such conditions of extreme exploitation, a neoliberal ideology that encourages personal expression through consumer devices—as celebrated by Apple—hardly seems plausible. (Admittedly, in Stephenson’s Diamond Age, a lead protagonist finds salvation through a self-customizing virtual reality device, but it is not fetishized; it works because it allows her to make a meaningful, albeit indirect, connection with another human being).

Cyberpunk’s allegiance is not to technology itself, but to a culture that values freedom for individuals. Technology is a means to an end. However, it would be misleading to say that the wired and well-equipped characters merely use technology in pursuit of liberation. Technology is not a “neutral” thing to be consumed when convenient. Instead, technology itself become a site of struggle. In fact, the focal technologies in these narratives are often destructive or oppressive by nature. The protaganists are generally hackers who must subvert intentions of the technology’s creators by fundamentally altering the nature of the technology itself to function in accordance with a competing set of values. In short, the protagonists and the antagonists are wrestling to shape technology to best fit there own goals and values.

Cyberpunk’s allegiance is not to technology itself, but to a culture that values freedom for individuals. Technology is a means to an end. However, it would be misleading to say that the wired and well-equipped characters merely use technology in pursuit of liberation. Technology is not a “neutral” thing to be consumed when convenient. Instead, technology itself become a site of struggle. In fact, the focal technologies in these narratives are often destructive or oppressive by nature. The protaganists are generally hackers who must subvert intentions of the technology’s creators by fundamentally altering the nature of the technology itself to function in accordance with a competing set of values. In short, the protagonists and the antagonists are wrestling to shape technology to best fit there own goals and values.

In Snowcrash, for example, Stephenson imagines a globally-connected digital environment that in many ways prefigures the modern Internet; though, Stephenson’s choice to label it “the Metaverse” is superior to the “virtual reality” moniker that ultimately prevailed in our culture, because the “meta-” prefix acknowledges an intrinsic connection to, or referencing of, the existing physical world, its values, and its pre-established power relations. In the story, the Metaverse is owned and controlled by then antagonist, who uses it as a tool of oppression. Stephenson envisions a world where digital information can physically manipulate and control the brains of programmers who are fluent in programming languages. In this case, the struggle to control the code is, literally, and existential struggle.

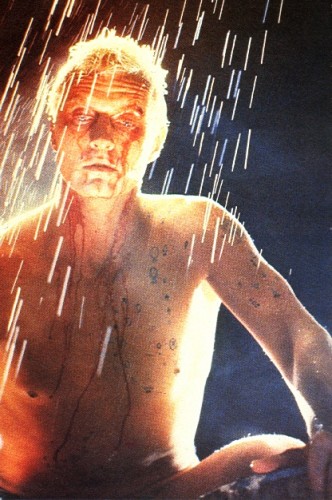

In contrast to consumer-oriented Futurism, Cyberpunk isn’t pretty. The environments course and polluted from centuries of human abuse. The settings offer an ideal-type of messy, “augmented reality,” with Tron‘s de-rezzer making literal the transformation from atoms to bits and The Diamond Age‘s synthesizers exemplifying the conversion of bits into atoms. Characters have a visceral relationship with technology, which they both depend on and are violated by. Returning again to The Diamond Age, we find swarms of nano-bots that invade, and even wage war inside of, human bodies. Yet, at the same time, these nano-bots also protect their hosts from outside pollutants. The Cyberpunk imagination bends the formal distinction between human and machine until it has little practical meaning. In this sense, we might call Cyberpunk characters “post-human.” However, these characters are still very much flesh and blood. Snowcrash introduces us to a breed of cyborgs called “gargoyles” that are burdened with heavy computer components and goggles and that, retrospectively, appear quite low-tech. As I discussed in a previous essay, when tools are so conspicuous, the limits of our (default) bodies remain readily apparent. Yet, even Bladerunner‘s fully synthetic replicants—in approximating the human body—must confront its limits. There is no Utopian transcendence of the flesh and blood. It is in this context that the otherwise gratuitous violence filling the genre’s pages and frames finds meaning.

In contrast to consumer-oriented Futurism, Cyberpunk isn’t pretty. The environments course and polluted from centuries of human abuse. The settings offer an ideal-type of messy, “augmented reality,” with Tron‘s de-rezzer making literal the transformation from atoms to bits and The Diamond Age‘s synthesizers exemplifying the conversion of bits into atoms. Characters have a visceral relationship with technology, which they both depend on and are violated by. Returning again to The Diamond Age, we find swarms of nano-bots that invade, and even wage war inside of, human bodies. Yet, at the same time, these nano-bots also protect their hosts from outside pollutants. The Cyberpunk imagination bends the formal distinction between human and machine until it has little practical meaning. In this sense, we might call Cyberpunk characters “post-human.” However, these characters are still very much flesh and blood. Snowcrash introduces us to a breed of cyborgs called “gargoyles” that are burdened with heavy computer components and goggles and that, retrospectively, appear quite low-tech. As I discussed in a previous essay, when tools are so conspicuous, the limits of our (default) bodies remain readily apparent. Yet, even Bladerunner‘s fully synthetic replicants—in approximating the human body—must confront its limits. There is no Utopian transcendence of the flesh and blood. It is in this context that the otherwise gratuitous violence filling the genre’s pages and frames finds meaning.

Cyberpunk authors in general, and Stephenson in particular, also view technology as contributing to a decline in centralized authority, which is supplanted by a patchwork of various organizations that are, at the same time, both more local and more global (i.e., “glocal“) than traditional states. The lack of a central government produces a Wild West type atmosphere, where danger and violence are pervasive, creating the conditions for a particularly masculine breed of heroism. This recourse to male-centered, rugged individualism is, undoubtedly, the movement’s weak spot—a problem that was practically begging to be remedied by feminist technoscience. When it comes to understanding individuals, these universes channel a bit too much Ayn Rand (and, perhaps, not enough Michel Foucault) to be quite believable.

Nevertheless, the Cyberpunk genre has much to offer to technology researchers because, as author Bruce Sterling explains, for Cyberpunks, “extrapolation, technological literacy—are not just literary tools but an aid to daily life. They are means of understanding and highly valued.” At its height in the 1980s and early 1990s, Cyberpunk gave us an ambivalent glimpse into the future—one where our lives are increasingly “augmented” by complex technologies. Most of all, it warn against the fetishization of technology. We must never be dazzled into forgetting that technology is a site of power; the consequences of falling prey to this illusion are, well, dystopian.

Follow PJ Rey on Twitter: @pjrey

Comments 19

sally — December 1, 2011

Nice piece, P.J.!

You write, "by burying the inner-workings of its devices in non-openable cases and non-modifiable interfaces, Apple diminishes user agency—instead, fostering naïveté and passive acceptance."

I kind of agree--to a point. Apple is fostering that in some end users. For others, though, it's a challenge to hack and to make around those sealed devices.

You may be interested in the AnthroPunk talk from MakerFaire May 2011, where Apple's history with sealed devices is discussed with regards to making, particularly from 10:29 - 12:40. Agency discussion follows as the talk progresses...(14:15 - 17:15 ish and onwards)

http://fora.tv/2011/05/22/Sally_Applin_AnthroPunk

Mike — December 1, 2011

I like the point about the masculine bias inherent in the DIY ethos -- to me, this is a fatal weakness, one that cannot be remedied. Reminds me of the first Matrix movie, which was popular because it rehearsed the familiar story of heroic mastery, dominance and control over the technological environment. Despite their weaknesses, I appreciated the way the 2nd and 3rd films problematized these simplistic cyberpunk ideas, showing how illusions of freedom are part of the overall functioning of the system as a whole -- an implicit critique of DIY/participatory culture's illusions of independence from corporate capitalism.

I think the series failed artistically because it failed to offer a real solution to this problem, but at least it asked the right question. But it failed more broadly in the culture because it did ask this right question, a question that we are not ready to ask.

Doug Hill — December 2, 2011

A very interesting piece, PJ. Among many sentences that jumped out at me was this one:

"The genre is characterized by the marriage of a deep interest in (and embrace of) modern technology with pessimism regarding the potential social consequences of this technology’s pervasive use."

That seems to me a fair description of the Devil's bargain we find ourselves in today.

The dystopian visions you describe from cyberpunk remind me of the almost hysterical sense of loss and dislocation expressed in H.G. Wells' final work, "Mind at the End of its Tether."

Cyborgology Weekly Roundup » Cyborgology — December 4, 2011

[...] PJ Rey provides an essay on Cyberpunk with a critical eye towards the role of the Ayn Randian rugged... [...]

Paul B. Hartzog — December 5, 2011

Mike, you are the first person I have ever seen make a cogent argument about why the 2nd and 3rd Matrix movies weren't total crap. Your possible point about "male" bias in DIY is less well articulated however. What's male about making? or are you re-ifying a gender stereotype you'd rather not? Do please google me and/or contact me online elsewhere.

genemorrow — December 9, 2011

Really brilliant PJ! I love the deeply critical look at cyberpunk. Also helps to explain why I'm never comfortable using an apple device that haven't rooted... Something about not having control of a device I use daily gives me the willies, now I know to blame my youthful reading! =D

The Great Geek Manual » Geek Media Round-Up: December 26, 2011 — December 26, 2011

[...] How Cyberpunk Warned against Apple’s Consumer Revolution [...]

Geek Media Round-Up: December 27, 2011 – Grasping for the Wind — December 27, 2011

[...] How Cyberpunk Warned against Apple’s Consumer Revolution [...]

NEWS ROUNDUP | Atlas Shrugged iPad App Wins Publishing Innovation Award, Cyberpunk vs. Apple, Angry Robot WorldBuilder, and More — Prometheus Unbound — February 4, 2012

[...] news, one P.J. Rey over at The Society Pages: Cyborgology has an interesting article about “How Cyberpunk Warned against Apple’s Consumer Revolution.” There are at times anti-corporate progressive and Marxist overtones in the article — [...]

Come i cyberpunk ci hanno avvisato della rivoluzione dei consumatori della Apple | Centro Studi Etnografia Digitale — February 6, 2012

[...] read the english version [...]

Who Fights For The Users? » Cyborgology — September 7, 2012

[...] Rey wrote an excellent piece in this vein a while back on Apple - probably one of the more egregious offenders here. Apple, PJ notes, makes use of an aura of [...]

Hipsters and Low-Tech » Cyborgology — October 1, 2012

[...] the quintessential example is the marketing of the iPod/iPhone/iPad which asks you to forget altogether the technical specifications of the product and instead immerse [...]

Hipsters and Low-Tech « PJ Rey's Sociology Blog Feed — October 4, 2012

[...] the quintessential example is the marketing of the iPod/iPhone/iPad which asks you to forget altogether the technical specifications of the product and instead immerse [...]

How Cyberpunk Warned against Apple’s Consumer Revolution » Cyborgology | Transhumanismo | Scoop.it — November 11, 2012

[...] [...]

Pope Francis, economics, and technological feudalism | Ironical Coincidings — March 14, 2013

[...] been snuffed out. I’ve seen people write about it as a shift from tools to platforms, a shift from active users to passive consumers, a shift from owning to renting, a shift (perhaps most evocatively) from anarchy to feudalism. All [...]