In preparing to write this post, I found myself going back over Whitney Erin Boesel’s post a couple of months back on death and digital/social media mediation, and I found myself running into a lot of the same issues she discusses. She suffered from massive uncertainty regarding how to talk about what she had experienced, or whether to talk about it at all. I’m going through the same. I’m not sure I should even be writing this, or what it will mean when I have. At the same time, I’m not sure how not to write about it, and that in itself is part of what I want to talk about.

Note: this is not going to be particularly organized, or particularly intellectual. It’s in part personal Livejournal-esque navel-gazing, part working through some disparate observations regarding how we deal with traumatic life events on social media, part general flailing around. Please bear with me. Or, you know, don’t.

Two Fridays ago, I was in New York to take part in a talk/presentation/art installation on video games put on by a collaboration between the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research and the Goethe Institut. I was pumped – it’s a topic that anyone who knows me knows I get excited about, and I was looking forward to some awesome discussions, to making new connections and new friends. And then I got a text from my mother telling me to call her immediately. So there I was, sitting in a Roy Rogers in Manhattan in front of a cooling roast beef sandwich with bizarrely loud jazzy R&B on the soundsystem, getting the news that a member of my family had taken his own life.

So that put an interesting spin on the day.

I should note that I’ve lost family members before, but never someone who wasn’t ill and/or elderly. I have been blessed enough to never lose someone like that until now. It was uncharted territory for me. How does one work through news like that? How does one process?

Along with the news, my mother delivered an iron-clad instruction: Do not talk about this on social media. At all. Not yet. Not everyone had been notified.

And the thing is, though I understood and respected and abided by the logic of that, my initial reaction was what? because I work through everything on social media.

This isn’t to say I have no filters at all, because I do. But I’m very forthcoming about what I’m feeling and thinking, to the point of being unprofessional. Since I began using the web in a social way back in junior high school, I’ve been using it as a sounding board for whatever I’m going through at the time. I put things out there via Facebook, via Twitter (especially Twitter), via my other journaling sites. Increasingly, I do that here. I’ve been doing it for so long that I don’t know how not to do it. It’s almost impossible for me to process powerful emotion without letting the world know that I’m feeling it.

I clammed up, at least for twenty-four hours or so.

But when I felt like I could reasonably start talking about it publicly – and I did, on Twitter – I found that I had profoundly mixed feelings about doing so. As Whitney noted, social media operates on an attention economy. Was I economizing on my own trauma? Was it my trauma on which to economize? Was I enjoying any of the attention I was getting – in the form of outpourings of love and support from my friends and even from mere acquaintances that I want to make it clear I am so, so thankful for.

What the hell was I feeling?

I found myself using Twitter as a mirror. I would write whatever I was feeling at the time, post it, look at it for a while and try to work through it from the outside in. I would study my own emotional output in an effort to make it all make sense. Suicide is at once nonsensical and profoundly rational, and as anyone who has ever lost someone that way knows tragically well, it’s nearly impossible to reconcile those two things. I was told over and over that there is no correct way to grieve, there is no right way to go about this, there is no particular thing that you should be feeling and yet I was gripped by the profound anxiety that I was doing something wrong. Then I would talk about that and try to understand it. Then I would worry about it some more. Now I’m talking about it here, and guess what, I’m still worrying.

I think this is what we do. Social media does encourage a kind of self-centeredness by its very nature, but I think it also encourages a deep connection with others – I doubt anyone here would really argue with that at this point – and I think both things are true simultaneously, because I think both things are true of almost all human communication, including just talking to someone else face to face. And how we express ourselves through social media is also how we make sense of ourselves, how we lay out our own narratives, how we explain ourselves to ourselves, even when we don’t actually make all that much sense – and we never really do.

But how do we do this? What’s appropriate? How should I have talked about this death, how specific should I be? Should I name names, should I detail the method, should I link to his memorial webpage? Whitney came to her own conclusions there, at least sort of:

It feels as though there is a certain degree of Very Close that one should be with someone before one steps anywhere near the limelight of their passing, and while I don’t know where the shadows stop and the light begins, I am certain that in that attention is not my place. In a way, new attention is like thermal energy: It flows from where there is more of it to where there is less of it. Were I quite a bit more well known than my friend, then linking would seem appropriate (even though we had long been out of contact): Here, pay attention. Here, help. In 2013, donations of social capital can be made in memoriam, too. Under the circumstances, however, I’ve been at an awkward loss—and unlike when I don’t know whether to send flowers or what to wear to a funeral, I can’t call my mom up to ask about this one. I don’t think any of us know yet. And the questions aren’t going away.

I want to talk about him in detail. I want to remember him like this. Social media is increasingly where we go both to remember and to forget, a place that is at once increasingly ephemeral, atemporal, and incredibly bound up in the passage of time. Things happen, people pass in and out of our lives, and we mark their passing this way. We record how they changed us, for better or worse; we understand them through how we lay out their pathways through our own experience. We understand each other. We understand what it means to lose someone, because we look at what we have of them and we know what they meant to us.

Except maybe we don’t. Because maybe there isn’t any way to do that at all.

The thing is, we weren’t in contact on social media. We weren’t Facebook friends. We weren’t following each other on Twitter. I don’t even know if he had a Twitter, though I know he had an Instagram account. So what I found myself dealing with on Twitter was entirely about me, entirely about what I was going through, and also entirely about this death and this loss almost as an objective fact unconnected to anyone specifically, simply an object out there in the universe like a rock or a star. On Twitter, it felt as if it was coming unmoored, drifting through my timeline without anything to anchor it.

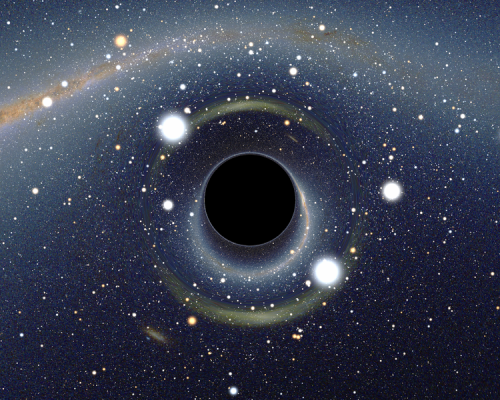

Elaine Scarry wrote a book about pain, and in that book she talked about pain as something unapproachable, something in the face of which all our rationality and all our tools of sense-making break down. In the face of pain we have no language. Like a black hole, we can’t see it directly. We can only measure it by what’s around it and by what effect it has on other bodies.

His memorial service was livestreamed. I was there. Apparently a lot of people watched. I wonder what that was like, what they were feeling. I wonder if they were posting about it. Before the memorial service, I saw pictures on Twitter of prayer gatherings for him at his school and I broke down crying. I had to fly home before the burial but I saw pictures of his casket on Twitter and I broke down again. The memorial service was a kind of closure but it also felt profoundly unreal. He wasn’t there. But on Twitter I felt like I got closer.

So my mother said to keep it off social media. What the hell does that even mean? And I still can’t bring myself to tell you his name. So all you have to measure his death by is me, what I’m telling you about what losing him meant to me. If he’s the black hole, I’m the body swinging out toward the event horizon, the pain is Hawking radiation, and none of it really makes any sense even now.

Death makes no sense, and it doesn’t make any more sense on Twitter. But if something like Twitter is the means through which we live a great deal of our lives, then death can’t be kept off of it. It finds its way there one way or another. It is there. And we look at it, puzzling, trying to approach it and what it means.

But all we see in the end are our own faces.

Sarah is on Twitter – @dynamicsymmetry