A couple of weeks ago, I made my first ever visit to China and I wanted to share some sociological observations with you about what I saw and experienced while I was there. My trip was under the auspices of my university’s International Programs Office (IPO) that’s in charge of all the study abroad programs on campus. From time to time, the IPO visits various study abroad sites around the world to make sure that they are high-quality programs for our students. Normally, the different staff at the IPO conducts these visits, but this time around, they asked me if I wanted to go to Beijing to check out the Council on International Educational Exchange’s (CIEE) programs in Beijing. It was an offer I could not pass up, so I jumped at the opportunity.

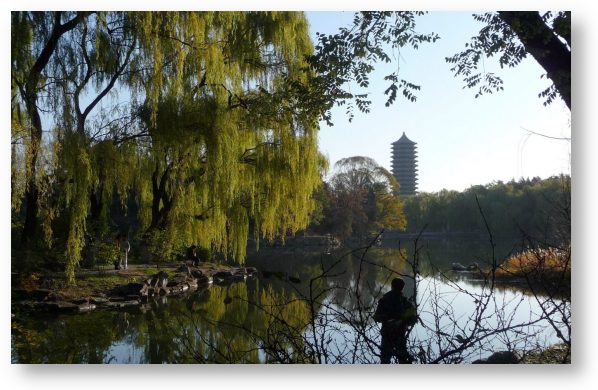

Specifically, the CIEE programs that I visited were based at Minzu University and Peking University. As the CIEE staff described to me, Minzu University was established in 1951 to basically assimilate members of China’s 56 ethnic minority groups (such as Tibetans, Uyghurs, Zhuang, Manchus, Hui, Miao, Yi, Mongols, etc.) into the majority Han culture. However, through the years, its focus and curriculum have evolved to become more tolerant and now promotes the retention of many aspects of culture and tradition among such ethnic minorities. Peking University is frequently called the “Harvard of China” and is considered to be the crown jewel of China’s university system. In its 2011-2012 ranking of universities around the world, the Times Higher Education listed Peking University as number 49 overall and as the top university in China.

Although I do not have anything to which I can compare these study abroad programs since this was my first such site visit, overall I found the CIEE programs at both universities to be comprehensive and impressive. There was a wide variety of academic and field opportunities for U.S. students at both schools to learn about Chinese language and culture inside and outside of the classroom. I found the staff there to be very friendly, professional, well-skilled, and enthusiastic about their programs. I also talked to a number of U.S. students currently studying abroad in these two CIEE programs and they all raved about the positive experiences they’ve had there. From what I saw during my site visit, I would certainly recommend these programs to my students.

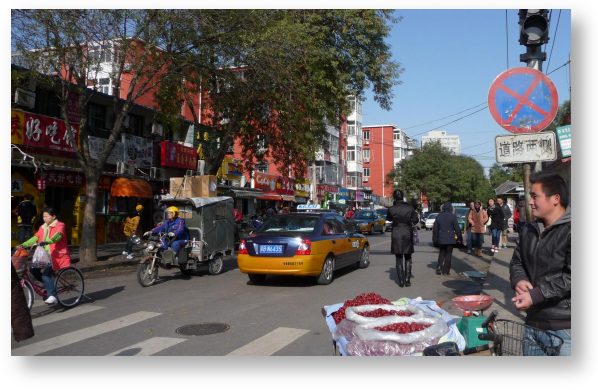

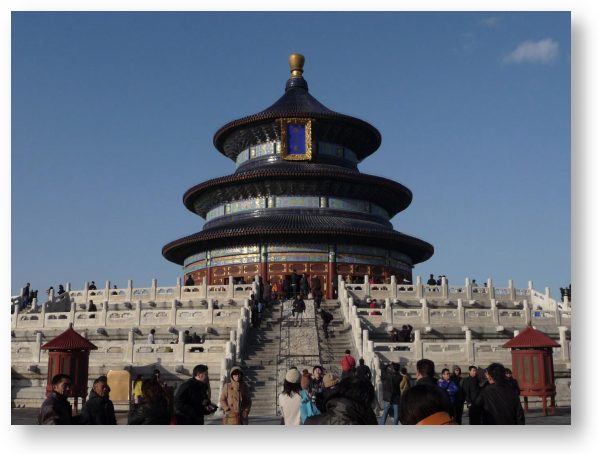

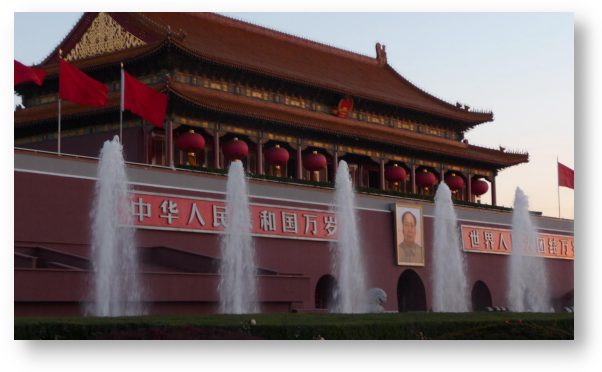

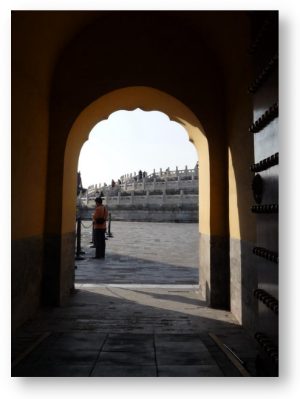

Below are a few pictures from my visit to China. You can view a more detailed photostream at my Flickr page.

China at a Crossroads

While I was in China and in my conversations with the CIEE staff and with both Chinese and U.S. students, a recurring theme was that China seems to be at a crossroads in its history and that there are two important issues within which China is struggling to find its balance in terms of where it wants to position itself politically, economically, and culturally within the global community. Each of these issues that I’ll discuss in more detail below represent a paradox or set of interesting contradictions that are playing themselves out within modern Chinese society.

I am certainly not the first observer, analyst, or scholar to discuss these issues, nor can I claim to have comprehensive expertise on such issues. Nonetheless, I would like to share my observations as a sociologist who wants to apply my academic interest in how Asians (and China specifically) fit into the contemporary global community in the 21st century and how Asian Americans fit into these international dynamics as well.

The first paradoxical issue concerns the growing sense of nationalism in China. This nationalism was most recently manifested in angry and sometimes violent protests against Japan over some small islands that lie between China (Diaoyu in Chinese) and Japan (Senkaku in Japanese) and are claimed by both countries. More generally, nationalism directed against foreigners has been evident in China for a while and from time to time, flares up and can turn ugly.

In my conversations with different people in China, they mentioned that a famous Chinese philosopher named Lu Xun observed about a hundred years ago that China frequently see themselves as either superior or inferior in relation to foreign powers, but never equal to them — it’s either a feeling of superiority or inferiority. With this in mind, nationalist feelings of superiority or inferiority need points of comparison. In modern times, China has two main international points of comparison — in Asia, it’s Japan and in the western world, it’s the U.S.

My contacts also observed that in most cases, the average Chinese citizen will rarely express such nationalist feelings directly to a foreigner, there was one instance in which this nationalism was directly visible to me and other site visitors in this trip. Specifically, a group of us (all from the U.S. involved in the CIEE site visit) was walking through Peking University when a Chinese male in his mid-40s came up to us and started speaking Chinese to us. Unfortunately none of us spoke Chinese, but even after we said that to him in English, he still kept speaking. We then pulled a Chinese American study abroad student (let’s call him ‘Keith’) who was accompanying us while we were at Peking University into the conversation. The Chinese man then turned his attention to Keith and as Keith relayed to us later, went into a tirade against the presence of foreigners in China. Although this man was not shouting, he was obviously very assertive in expressing himself. Considering the recent protests against Japan, this was probably a relatively mild form of nationalism that we experienced.

The contradiction here is that China very much wants to attain a position of respect and status within the international community and wants to continue attracting international investment and promoting global trade. In other words, it needs to engage with the international community. But on the other hand, a large part of the national discourse within China emphasizes China’s superiority over foreign powers and in fact, advocates limiting or even eliminating the presence of foreigners inside China.

An interesting component to this emerging nationalism in China is that much of it was initiated and encouraged by the Chinese government, at least in the beginning. As other analysts have pointed out, when it comes to particular issues such as the disputes with Japan, Chinese government officials have tried to maintain a sense of diplomacy in public while behind the scenes, frequently allowed or even facilitated nationalist rhetoric and citizen protests to serve their political interests. The problem however, is that the Chinese government may be losing control over this nationalist monster that they’ve created. As one of my contacts noted, when you keep feeding the citizens ‘wolves’ milk,’ eventually they’ll grow up to be wolves.

I have written about this kind of “cultural schizophrenia” in China before. On the institutional and national level, this sense of fluctuating between two extremes while trying to find your identity is actually similar to what many Asian Americans face on the individual level as they try to balance the ‘Asian’ and ‘American’ sides of their identity. In China’s case, as it tries to solidify its position in the international community, it’s likely that such internal struggles will continue to take place and it remains to be seen how the emerging contradictions between the government’s ‘Dr. Jekyll’ and the nationalists’ ‘Mr. Hyde’ will play themselves out.

Where Do Chinese Americans Fit Into China?

The second sociological dynamic that I observed while in China relates to where Chinese Americans fit into modern Chinese society. Like a number of other Asian American scholars, I have a growing interest in looking at how Asian Americans fit into Asian societies and how they use both their Asian and American identities to potentially bridge the political and cultural gaps between the U.S. and Asian countries. As such, I was very interested in hearing from Chinese American students and their experiences studying abroad in China.

In addition to ‘Keith’ (mentioned above), I also spoke at length to another Chinese American student; let’s call her ‘Kathy.’ They both described similar experiences of feeling caught in a “cultural limbo” while in China. That is, on the one hand, their physical appearance is Asian and more specifically, Chinese. But on the other hand, their nationality is American. This frequently means that upon first contact, most Chinese nationals assume that they are Chinese. But once they start talking, they are quickly seen as American, even though they speak Chinese pretty well.

Both Keith and Kathy noted to me that once this happens, more often than not, Chinese nationals lose interest in speaking to them. I asked them why and they said that Chinese tend to be more interested in talking to ‘regular’ Americans — i.e., White Americans. In other words, even within China, while they are treated generally as Americans (rather than as Chinese), Chinese Americans are generally not seen as representing the ‘normal’ image or perception of what Chinese think of as ‘American’ — i.e. they are not White.

Nonetheless, Kathy and Keith told me that once they got used to this cultural dynamic, they were eventually able to create and embrace their own “Chinese American” identity that is neither completely Chinese nor completely American, but a fluid combination of both. Upon doing this, they said that they felt more comfortable using this identity to begin bridging the cultural gaps between China and the U.S. in small ways during their stay in China.

This process of creating an ‘Asian American’ identity that combines and bridges two sets of cultures is what Americans of Asian ancestry have been doing for centuries. It is with this understanding in mind that I think Asian Americans are positioned to take make tangible contributions toward applying their globalized and transnational characteristics and experiences to bridging the political and cultural gaps between the U.S. and Asian countries. In fact, scholars are beginning to examine and describe examples of Asian Americans in different social settings acting as ‘cultural ambassadors‘ in Asian societies.

Therefore, if countries such as China continue to pursue a position of respect within the wider international community while still retaining elements of their national identity, they can learn from Chinese Americans who have have years of experience and expertise in doing exactly that — integrating themselves into mainstream U.S. society while keeping elements their Chinese culture intact. This is not to say that it has been a seamless or smooth process and in fact, Chinese- and Asian Americans have been and continue to face suspicions and challenges regarding their ‘real’ identity.

Nonetheless, institutional changes taking place, such as the ongoing effects of globalization, greater transnationalism, and increased multiculturalism, have transformed the racial, ethnic, and cultural landscape of both U.S. society and the world in general. Within this new social environment, there are new opportunities for minority groups such as Asian Americans to assert an identity that legitimately incorporates elements of, and for the benefit of, different societies and cultures.

There is an old Chinese saying that goes, “May you live in interesting times.” From a sociological point of view, this is indeed a very interesting time for China and there are a number of interesting ways that Chinese Americans (and Asian Americans as a whole) can participate in forging a more inclusive path forward into the 21st century.

This article originally published at Asian-Nation.org and is copyrighted © 2013