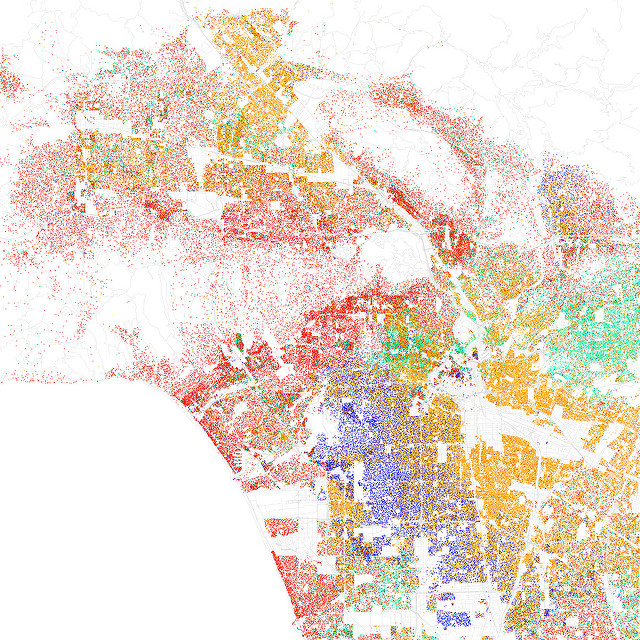

We know that a college degree can often help ensure employment, creating pathways to better opportunities and resources in someone’s career and even one’s personal health. A recent article in The Washington Post shows that the health benefits of higher education are more nuanced than scholars originally believed. Drawing from the work of sociologists Andrew J. Cherlin and Jennifer Karas Montez, the article demonstrates that location, race and ethnicity, and even expectations all shape the relationship between a college degree and health.

College degree attainment is related to many health benefits, including longevity. In recent years, White Americans without college degrees faced increasing mortality rates, while Black and Hispanic Americans showed overall advancements in their longevity, even among those without a degree. Andrew Cherlin argues that expectations are particularly important for understanding why there are clear racial differences in the link between degrees and health benefits. As the article outlines,

“It wasn’t long ago that white working-class Americans could count on leading a comfortable life with just a high-school degree. Middle-aged men and women, the very group falling ill and dying, are the first generation without that guarantee. They compare themselves with their parents and find their lives falling short. For black and Hispanic Americans, if you haven’t got as much to hope for, you might just have less to lose.”

Geography and economic differences add more complexity to unpacking the causes of health disparities. Living without a degree in areas that are heavily impacted by economic shifts and with inadequate medical resources like the rural United States can further exacerbate health problems. As Jennifer Karas Montez suggests, tackling these issues on a large scale is even more difficult given that public policies are created at state and local levels. In short, the relationship between health and college attainment is complex. Having a college degree does not directly translate into health benefits and vice versa — those without a college degree are not fated to poor health.