The U.S. presidential election is beginning to take on issues of poverty and class. Such conversations often look at “the poor” from a careful remove, but work by Thomas Hirschl of Cornell and Mark Rank of Washington University says that outsider angle is a comfortable farce. As explained by an article in Salon, the unpleasant fact is that over fifty percent of Americans will experience poverty during our lifetimes. Impoverishment and “the poor”—and the politics and policies that affect them—are actually very close to home.

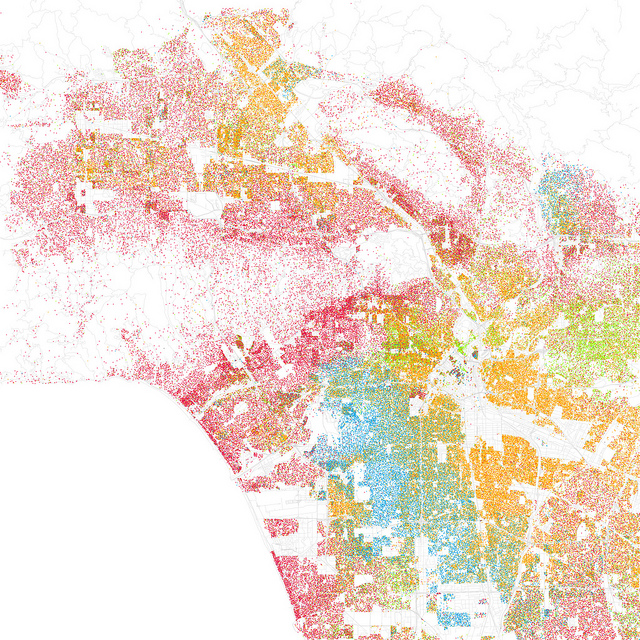

Of course, demographic factors are a big part of predicting one’s likelihood of experiencing poverty. (If you’re interested in calculating your own odds, check out Hirschl and Rank’s poverty calculator!) Education is one big factor, as is race: white people are half as likely as non-white people to fall into poverty. And married people are less likely to become poor than singles. Still, as candidates and voters debate nature of class and poverty in America, we would do well to remember that they affect us all. To pretend like anyone’s above poverty would be a poor show.