Hate ordering a coffee and a scone, laptop in tow, only to find out that all the good tables next to the outlets are taken? Coworking spaces seem to be the affordable solution. Upscale urban restaurants –looking to make money during morning and afternoon off-hours — have started partnering with coworking startups to provide affordable workspaces with power strips, fast wifi, and bottomless coffee and tea. In a recent Vox article, Gaby DelValle calls upon the work of sociologist Dalton Conley to describe this latest trend in ‘weisure.’

“In his 2009 book Elsewhere, USA, Princeton University sociologist Dalton Conley referred to this as ‘weisure,’ or the merging of work and leisure. This breakdown of the boundary between labor and enjoyment, Conley wrote, is ultimately destructive, even if it’s disguised as a boon for both employee and employer.”

Coworking spaces, like Spacious in New York City, are expanding as more workers turn to freelancing or telecommuting. Having the freedom to work from anywhere may eliminate some of the role conflict experienced by people trying to juggle work, family, and their social life, but it also means they need a place to work from. Many workers find coworking spaces preferable to coffee shops because of the amenities and the camaraderie of working among other people. Yet, Conley explains, the shift to coworking also has less desirable consequences.

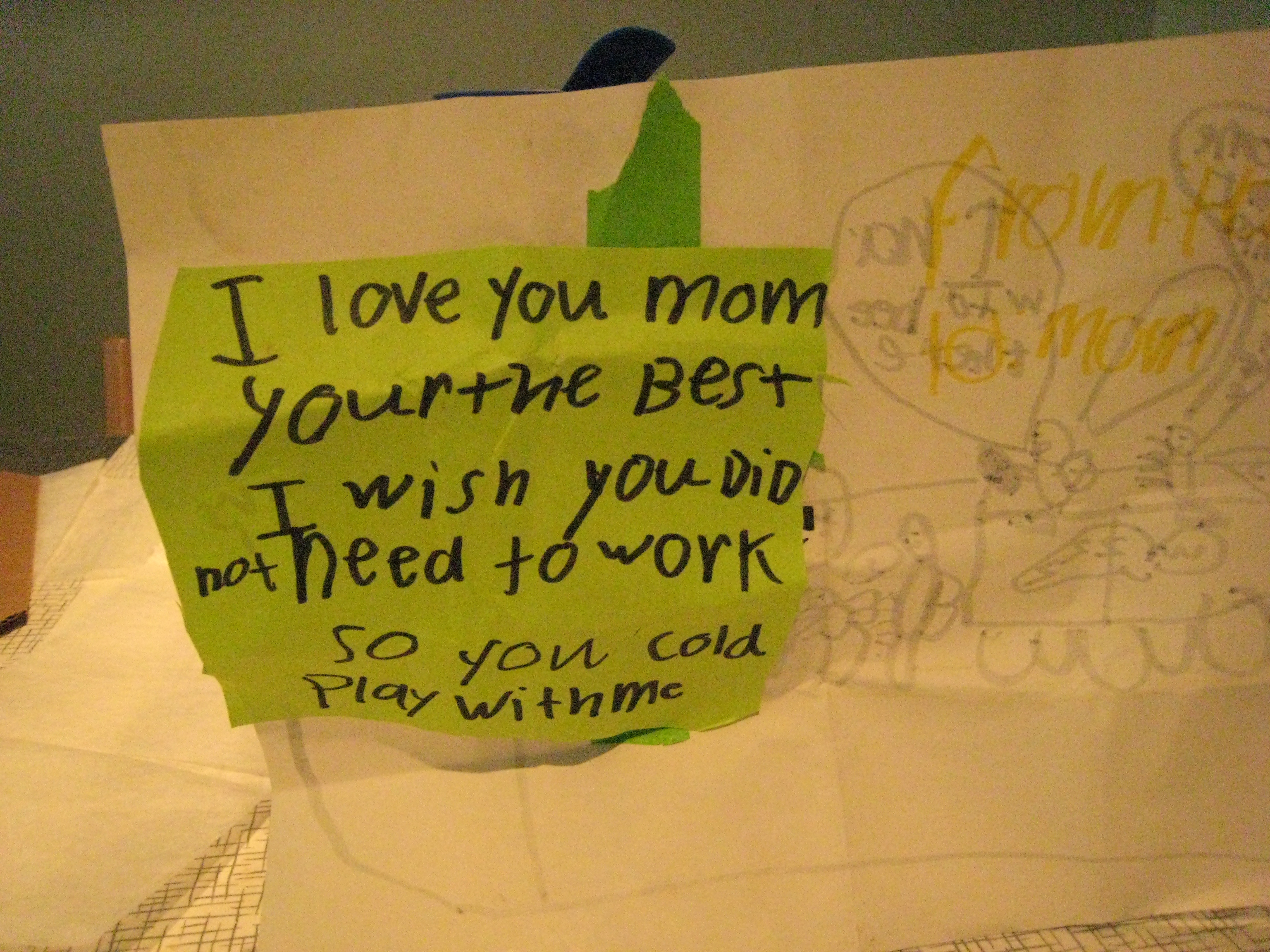

“This work-and-play blurring ends up enhancing [their] sense of alienation,” he wrote. “It’s not just that they feel like they need to be working when they are ostensibly supposed to be having fun or, conversely, that they should stop working and be there for their kids, spouse, or friends. It’s not just that [they] need to be everywhere at once. It’s that once disparate spheres have now collided and interpenetrated each other, creating a sense of ‘elsewhere’ at all time. … Home is more like work and work is more like home and the private and public spheres are indistinguishable from each other.”

As Conley explains, coworking is part of a larger trend of blurring distinctions in the social world: home–office, work–leisure, public–private, and even self–other. The result for many is a sense of alienation: No matter where we are, we’re always wondering where we should be and where we need to be. When we participate in ‘weisure,’ we feel that we should be ‘elsewhere.’