We often hear how Facebook, Twitter, and other social media contribute to protests and demonstrations by allowing activists to express their views or coordinate their actions. Social media were a big part of Arab Spring, but they were also a large part of the Reformation, says an article from The Economist. Nearly 500 years ago, Martin Luther went viral by circulating pamphlets, woodcuts, and other social media of that day in order to spread the message of religious reform.

The start of the Reformation is generally explained as a three-step process: 1. Martin Luther gets fed up with members of the Catholic Church asking for money to free souls, 2. Luther pins a list of 95 Theses (in Latin) to the Church door, and 3. The Reformation has begun. But, a closer look reveals Martin Luther spent more time thinking about social media:

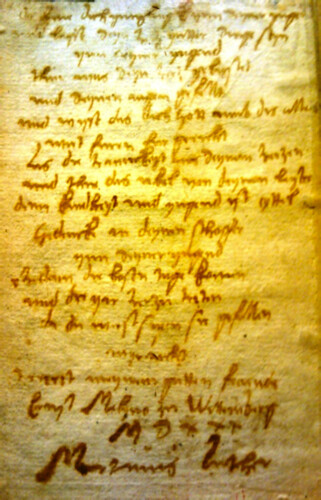

The unintentional but rapid spread of the “95 Theses” alerted Luther to the way in which media passed from one person to another could quickly reach a wide audience. “They are printed and circulated far beyond my expectation,” he wrote in March 1518 to a publisher in Nuremberg who had published a German translation of the theses. But writing in scholarly Latin and then translating it into German was not the best way to address the wider public. Luther wrote that he “should have spoken far differently and more distinctly had I known what was going to happen.” For the publication later that month of his “Sermon on Indulgences and Grace”, he switched to German, avoiding regional vocabulary to ensure that his words were intelligible from the Rhineland to Saxony. The pamphlet, an instant hit, is regarded by many as the true starting point of the Reformation.

While it sounds pretty different (imagine communicating through woodcuts!), the media environment Luther circulated in shared some similarities with today. It was a decentralized system in which participants distributed messages through sharing—Luther passed the text of a pamphlet to a friendly printer, who could print the small text in a day or two. Copies of this first edition, which cost about the same as a chicken, spread through the town they were printed in, being picked up by traveling merchants, preachers, or traders, and spread across the country. Local printers would then reprint their own editions, much like Facebook “shares” or Twitter “retweets.”

And, as with collective action in the 21st century, social media could be dangerous during the Reformation:

In the early years of the Reformation expressing support for Luther’s views, through preaching, recommending a pamphlet or singing a news ballad directed at the pope, was dangerous. By stamping out isolated outbreaks of opposition swiftly, autocratic regimes discourage their opponents from speaking out and linking up. A collective-action problem thus arises when people are dissatisfied, but are unsure how widely their dissatisfaction is shared, as Zeynep Tufekci, a sociologist at the University of North Carolina, has observed in connection with the Arab spring. The dictatorships in Egypt and Tunisia, she argues, survived for as long as they did because although many people deeply disliked those regimes, they could not be sure others felt the same way. Amid the outbreaks of unrest in early 2011, however, social-media websites enabled lots of people to signal their preferences en masse to their peers very quickly, in an “informational cascade” that created momentum for further action.

Something very similar happened in the Reformation. A1523-24 surge in reform-pamphlet popularity (including those written by Luther and many others) served as a collective signaling mechanism of Luther’s support. Luther had been declared a heretic, but, because of his supporters, he was able to escape execution, and the Reformation became established in much of Germany. The power of social media is anything but new.

Comments 3

Letta Page — December 30, 2011

I love this line:

Luther wrote that he “should have spoken far differently and more distinctly had I known what was going to happen.”

We should all be more deliberate in our communications... who knows how far they'll spread!

Tides Of Change Gradually Erode Unbending Institutions | Living History — March 7, 2012

[...] Friendly Universe - Law of Attraction in Action Day 167 of 2011: "Tides Of Change Gradually Erode Unbending Institutions" by Jerry Waxman The inter...as brought people to where they've never been before. People are free to express themselves online [...]

jo. mamma — January 8, 2020

you suck