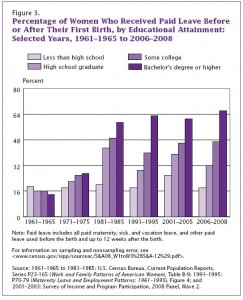

- Caitlyn Collins (Associate Professor of Sociology at Washington University in St. Louis) recently appeared on The Ezra Klein Show to discuss how national policies, social support, and culture affect experiences of parenthood. Collins describes how work-family policies in Sweden and the United States affect how we think about parenting, clashes between the roles of worker and parent for Americans, and more.

- Christina Cross (Assistant Professor of Sociology at Harvard) was recently accused of plagiarism in an anonymous, bad-faith complaint. The complaint focuses on instances of boilerplate descriptions of datasets and instances where scholars are cited, but not quoted. This accusation–the fourth in a series of complaints against Black women at Harvard who study race or social justice–has been amplified by conservative activist Christopher Rufo as part of a broader campaign against critical race scholarship and DEI efforts. Plagiarism expert Jonathan Bailey reviewed the allegations and found no issue. However, Bailey is concerned with the “weaponization of plagiarism” (using allegations of plagiarism to address political or social grievances). In support of Cross, the ASA denounced the anonymous complaint: “These false claims of plagiarism are a political attack that exploits the gap between the normal scientific process and the public’s understanding of that process. These actors also appear to be working to undermine faith in the research process and delegitimize academic knowledge by attacking racial diversity and the inclusion of highly qualified Black faculty and leaders in colleges and universities.” This story was covered by The Harvard Crimson.

- The New York Times recently reviewed Amin Ghaziani’s (Professor of Sociology at the University of British Columbia) new book, Long Live Queer Nightlife: How the Closing of Gay Bars Sparked a Revolution. Ghaziani recounts the gay bar “closure epidemic” and the rise of a re-imagined queer nightlife, built upon ad hoc club nights and underground parties.