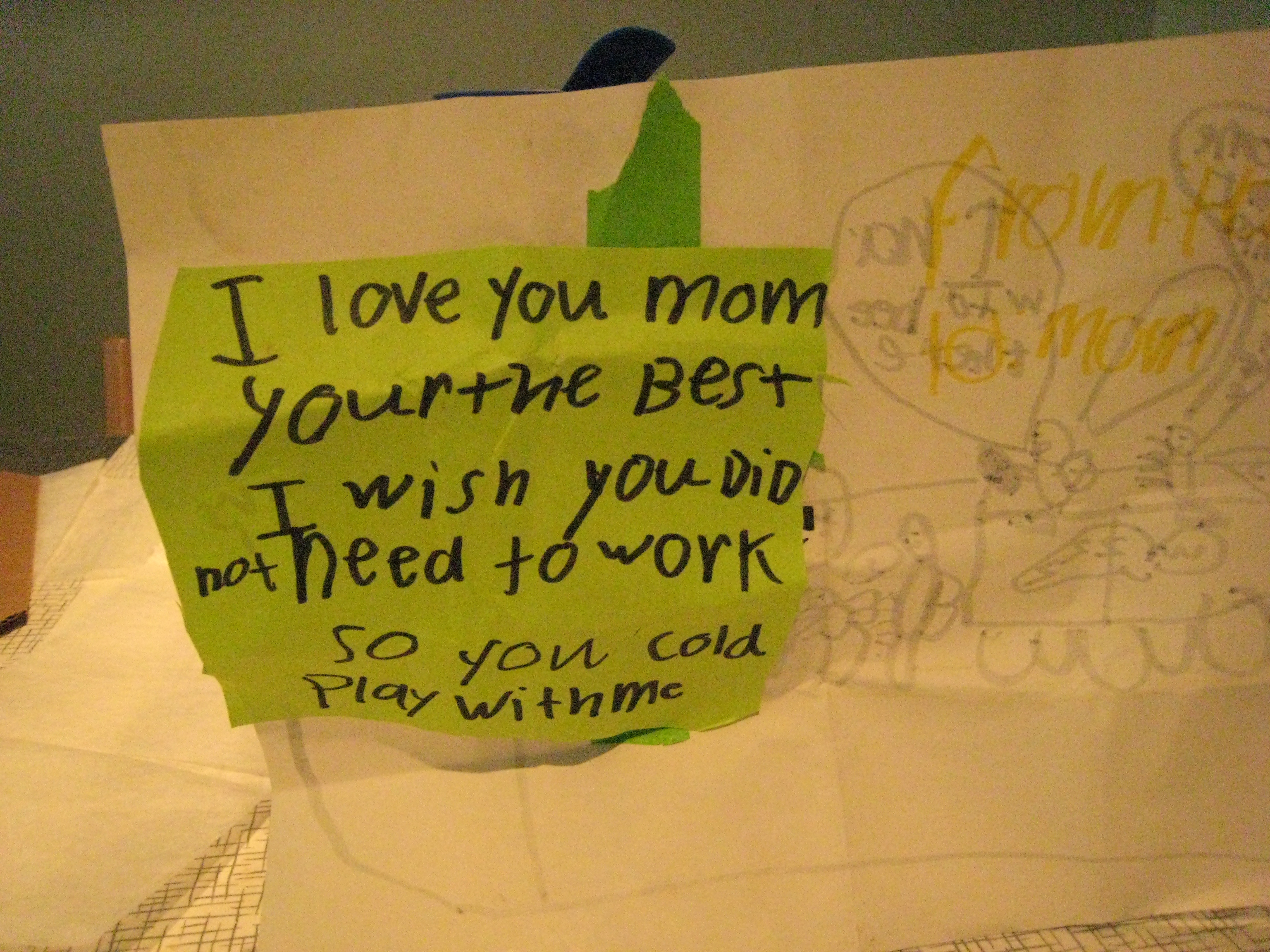

For years, legislators and employers have framed guaranteed parental leave as a “women’s issue.” Women serve as the primary advocates for policies that allow more flexibility between work and family life, while fighting stereotypes that paint them as less committed to their jobs than men. In a recent article for Fast Company, sociologist Michael Kimmel discusses how the U.S. lags behind every other industrialized country in policies that guarantee parental leave and how he believes this contradicts “family first” ideals. “Supporting families is the very definition of family values,” writes Kimmel. “How can we possibly lecture others about loving and supporting families when we value our own so little?”

One key to the gradual change that’s come to cities including New York, Washington D.C., and Chicago may be a shift in male perspectives of household work. Recent surveys suggest many men want to be more involved in household duties. Despite that willingness, however, women still bear much of the burden. Consequently, fathers are often praised for more public acts of parenting, like taking children to soccer practice, while mothers are more likely to take care of unsung housework, struggling to also meet the demands of their careers. Further, researchers note that demanding careers cause increased risks of physical and mental illnesses such as heart disease, diabetes, and stress for everyone, not just fathers or mothers.

As legislators craft a new wave of parental leave policies, many question how employers can provide a working environment to support parents and families. In a recent study, Phyllis Moen and Erin Kelly studied the Star Initiative program that allowed for increased flexibility for 700 employees at a Fortune 500 company. The aim was to provide employees with more flexibility in attending meetings, working from home, and communicating via instant messenger. After one year, those involved in the initiative reported greater job satisfaction and lower rates of poor mental health. According to Kelly, “One important implication of this research is that workplaces can change to bring some relief to stressed out workers. It’s not up to an individual to figure out how to balance everything. Challenges come up with work, but organizations can change to bring some relief.”