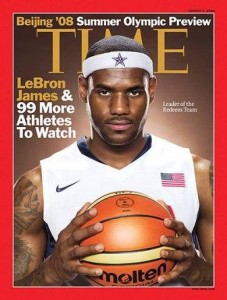

When ESPN began broadcasting LeBron James’ high school games to a national audience some years ago, basketball fans asked, “Is he the next Michael Jordan?” Last week, James capped off the 2012-2013 NBA season with his fourth MVP award, leading the Miami Heat to a second consecutive championship (he really did “take his talents to South Beach”). It only cause more people to wonder if James could equal—or surpass—Jordan’s legacy.

Michael Eric Dyson, a sociologist at Georgetown University, made a guest appearance on ESPN’s “First Take” to offer his perspective on the similarities and differences between the two basketball greats, both on and off the court.

As Dyson explained, social movements and commercialization combined when Jordan was drafted by the Chicago Bulls in 1984. The Civil Rights Movement had passed; communication technology which could carry photos, highlights, and live games around the planet was improving; and the NBA’s new commissioner, David Stern, was intent on expanding the league’s global footprint. In Michael Jordan, Stern had found a charismatic ambassador for basketball. Dyson notes, “Jordan comes along at a time when people began to celebrate a tall, dark, handsome, physically lethal specimen who also has the ability to commodify… So when you have the marketplace joining the morality of social advance, that’s something that’s incomparable.”

While “King James” follows in Jordan’s footsteps commercially, Dyson argues that they’re different types of players on the court. Jordan was known for his legendary competitive drive and “killer instinct,” while LeBron, particularly since teaming up with fellow stars Dwyane Wade and Chris Bosh in Miami, has earned a reputation as a facilitator who works to involve his teammates as much as possible, perhaps even to a fault.

Like MJ before him, LeBron James is now the global face of the NBA—some love him, some hate him, and most basketball fans are fascinated by him. The marketing of and commentary about the two men’s talents, bodies, and identities provide a rich source of study for social scientists interested in race, media, sport, and culture over time.