Racial categories are often imposed or assigned, and one’s race tends to be thought of as an immutable quality. One’s ethnic identity, on the other hand, is more likely to be a chosen identity — related to cultural factors, traditions, and family history — but is sometimes conflated with race. When multiracial identities are involved, racial and ethnic categories are especially malleable, and many population surveys like the U.S. Census do not allow for this complexity. A recent NBC News article draws from sociological research to argue that the 2020 census should capture racial and ethnic identities for a more accurate picture of the Latino population.

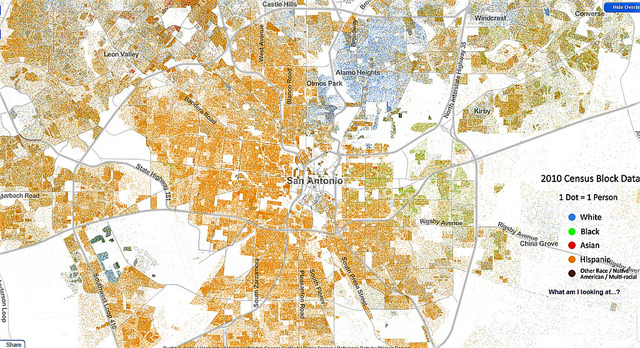

Sociologist Richard Alba argues that the current U.S. Census divides America into two groups: white and non-white. Of the non-white population, the current largest group are individuals with mixed Hispanic and white European ancestry. However, prior censuses — based on the two-question format on ethnicity and race — do not reflect or allow for ambiguities and realities of mixed racial and ethnic identities for Latinos in the United States. Children of these mixed-race families, even though they have a white parent, are counted as non-white, and this obscures the blending and racial change for some parts of the Latino and Asian populations in the United States.

How we see ourselves racially is not always what race others may ascribe to us. In his 2015 study, sociologist Nicholas Vargas found that 42 percent of Hispanics identified as white, but only 6 percent were perceived as white by other Americans. This highlights the importance of differentiating between assigned racial identities and proclaimed ones.

Some researchers do not believe the U.S. Census is an effective tool to measure racial identity. In her book, Manifest Destinies, Laura Gómez writes:

“the [Census] has to look beyond racial categories of being white and nonwhite — which reflects more the historic attitudes imposed by society on different groups than the mixed reality of modern-day America — and make it more inclusive to encourage greater participation and accuracy.”

However, the 2020 Census will keep the same formatting, going against a decade of research on Latino identities — identities that do not rely solely on skin color or racial descent. As census-takers grapple with the constrictive format for questions that measure racial and ethnic identity, these problems of accurate representation will remain.