Gentrification is rapidly transforming once-industrial cities into trendy urban neighborhoods. However, the dangers that lie below the surface – “hundreds of millions of pounds” of hazardous wastes released by small and large businesses each year – fail to be addressed at the same rate. In a recent interview in The Guardian, sociologists Scott Frickel and James R. Elliot discuss findings from their book about the limitations of current data on environmental hazards and how gentrification has diversified the types of people at risk of exposure to toxic waste.

Frickel and Elliot explain that government databases on hazardous sites only appeared in mid 1980s, and databases often exclude manufacturers that have few employees or release under a specified threshold of pollutants. Reporting is also completely voluntary, meaning the databases only contain the information facilities choose to report. In their research, Frickel and Elliot use old manufacturing directories to address these limitations by creating their own database. They found manufacturing to be heavily concentrated in certain “legacy sites,” or areas where you would expect to find heavy industry with large concentrations of factories or other facilities. However, these site boundaries also spread out slowly over time, and so too did the hazardous wastes. While disadvantaged social groups are more typically exposed to these pollutants, gentrification has disrupted this to some extent. Elliot explains,

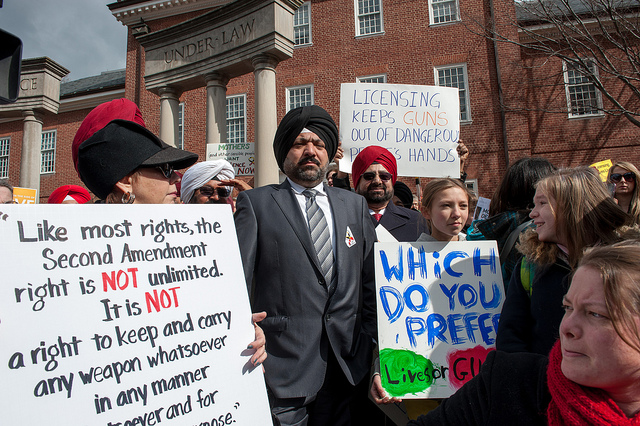

“We do also find things that we’ve come to unfortunately expect from the vast research on environmental injustices… These larger facilities are opening up and disproportionately concentrating in areas of ethnic minority and low-income settlement. But when we begin to consider the spread and the accumulation across cities as land uses change, that picture also changes. We begin to see, as one of our colleagues put it, that we’re all in this together. Many different types of neighborhoods are exposed.”

To remedy this exposure to hazardous materials, Frickel suggests that urban planners seriously consider the history of pollutants that exist below our cities when addressing sustainability. It remains to be seen how gentrification will impact citizens’ ability to hold businesses and government officials accountable for these environmental hazards, but recent events such as the water crisis in Flint should serve as a key example of how far we have left to go to address toxic hazards.