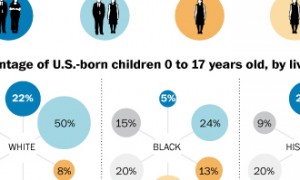

That’s likely true for a lot of reasons, but one is just coming to light: For many African-Americans, working for the government has provided a gateway to the middle class. “Compared to the private sector, the public sector has offered black and female workers better pay, job stability and more professional and managerial opportunities,” sociologist Jennifer Laird tells The New York Times. The civil service, delivering mail, teaching, operating public transportation, and processing criminal justice have historically provided steady income and opportunities to climb the economic ladder—often without an expensive college degree.

The recession’s recovery has not brought back employment at the local, state, and federal levels, though, and it’s causing struggle in black communities in particular. Population growth has also meant higher competition for ever scarcer public sector jobs. African-Americans once benefitted most from government employment, so cutbacks and layoffs hit them the hardest. Laird describes black government workers’ situation as a “double-disadvantage”:

They are concentrated in a shrinking sector of the economy, and they are substantially more likely than other public sector workers to be without work.